The taking of Neuve Chapelle by the British, March 1915

Winter

By the end of 1914, the Allies and the Germans had established themselves in a line of trenches running from the Channel to the French-Swiss border. Until March 1915, artillery exchanges, sniping and mining operations were the main activities on the British Expeditionary Force’s (BEF) front.

As both sides settled down for the first winter of the war, the weather proved harder to contend with than the enemy in some sectors. Artillery bombardment rapidly destroyed trenches, which had been built quickly and tended to be simple affairs. The bad weather and the destruction of pre-war drainage ditches also led to widespread flooding.

But no matter how cold or wet they were, the soldiers had to remain in the line.

The Prince of Wales's Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians) at St Eloi, 1915

‘Poured with rain all day and night. Water rose steadily till knee deep when we had the order to retire to our trenches. Dropped blanket and fur coat in the water. Slipped down as getting up on parapet, got soaked up to my waist. Went sand-bag filling and then sewer guard for 2 hours. Had no dug out to sleep in… In one place we had to go through about 2 feet of water. Were sniped at a good bit… Roache shot while getting water and Tibbs shot while going to his aid. He laid in open all day, was brought in in the evening, unconscious but still alive. Passed away soon after.’

Rifleman William Eve’s diary entry - 7 January 1915

Neuve Chapelle

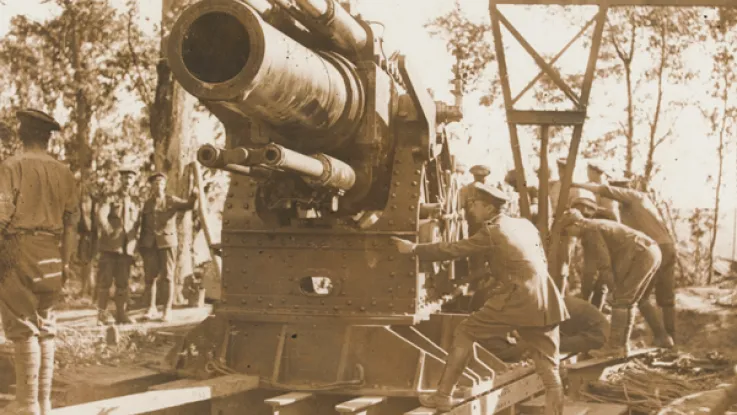

The first major British offensive of the First World War took place on 10 March 1915 when they attacked the salient around the village of Neuve Chapelle, midway between Bethune and Lille. The assault was undertaken by General Sir Douglas Haig's First Army, with Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson's IV Corps on the left and General Sir James Willcock's Indian Corps on the right.

Although the initial artillery bombardment was too light to entirely disrupt the enemy defences, the first phase of the infantry attack went well. The soldiers rapidly gained the German front-line trenches. By nightfall Neuve Chapelle had been captured.

Indian bombers at Neuve Chapelle, 1915

Gurkhas at Neuve Chapelle, 1915

No breakthrough

Unfortunately, there were delays in sending forward further orders and reinforcements. The initial gains were not exploited and a German counter-attack prevented further progress. After three days of fighting, a small area of land had been gained at a cost of over 7,000 British and 4,000 Indian casualties.

The offensive showed that although it was possible to break into the German positions, it was not so easy to convert local success into a major breakthrough. It also showed that a heavier artillery bombardment and better communication were needed.

The Garhwal Rifles marching down La Bassee Road, 1915

Shell and political crisis

After the battle, the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French, blamed the attacks's failure on the lack of available shells. This led to the 'Shell Crisis' of 1915 and the collapse of Herbert Asquith's Liberal Government.

A new coalition government was formed with Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions. The creation of this new post was recognition that the whole economy would have to be geared for total war if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front.

Women workers engaged in shell-production, c1915

Gas at Ypres

On 22 April 1915, the Germans attempted to capture the Ypres Salient, a bulge in the Allied line surrounding the Belgian town of Ypres. They used poisonous gas for the first time, exploiting the latest in scientific weaponry in the hope of breaking the stalemate.

The release of chlorine gas opened a hole in the line four miles (7km) wide. The effect was devastating and the stunned Allied troops fled in panic towards Ypres. Over 10,000 men were gassed; around half of them died that day.

However, the German High Command had underestimated the effectiveness of gas in bringing about a breakthrough. As a result, insufficient reserves were made available to exploit the gap created by the gas cloud and support the infantry units that had followed it. After advancing about 1.5 miles (2km), the Germans were checked by a hastily arranged counter-offensive.

The fighting raged on at Ypres until 27 May, with repeated use of gas. The Germans did not break through, largely thanks to the Canadians. But they reduced the size of the Allied salient. There were nearly 70,000 Allied and 35,000 German casualties during the battle.

Wounded and gassed from Ypres at hospital in Bailleul, May 1915

British soldiers in the trenches at Wulverghem near Ypres, 1915

‘Had a fair view of Ypres burning. It has been heavily shelled all day and we have evacuated it... More Canadian wounded came in by motor ambulances, mostly stretcher cases... Several suffering from poisonous gases – depression, poor pulse, cyanosis and considerable bronchial irritation… several have been killed by this means. The Germans have a special corps for this work armed in India rubber suits and respirators. At a given signal they start the gas from cylinders which is heavy greenish brown in colour and blows towards our trenches.’

Diary of Lieutenant-Colonel Howard Dent, Royal Army Medical Corps - 23 April 1915

Aubers Ridge

On 9 May 1915, the British made a two-pronged attack on the German line in support of a French offensive at Artois. The southern thrust - consisting of the Indian Corps and British I Corps - aimed towards Aubers Ridge. IV Corps, three miles (5km) to the north, headed for Fromelles.

However, the artillery barrage was too light and inaccurate. There were delays in sending forward reinforcements, and much of the German wire remained uncut. By the following morning the British had been forced back to their start line, having suffered 12,000 casualties.

Festubert

On 15 May 1915, the British shifted the focus of the offensive southwards to the German positions near Festubert. Under the cover of darkness, the attacking divisions made some progress, but the barrage had failed to significantly damage the German lines.

Although Festubert was captured, the British and Indians suffered around 16,000 casualties before the offensive ended on 25 May.

French machine-gunner on the Champagne Front, 1915

French troops don their gas masks, 1915

Loos

On 25 September 1915, the Allies launched a new joint attack. The French went on the offensive in Champagne and Artois. The British fought at Loos, where they used chlorine gas for the first time. Despite heavy casualties, by the end of the first day the troops had succeeded in breaking into the enemy positions near Loos and Hulluch.

Supply and communications problems, along with the late arrival of reinforcements, meant that the breakthrough could not be exploited. The attacks ground to a halt and by 28 September the Germans had pushed the British back to their starting points.

Members of a Red Cross ambulance resting, 1915

‘The gas hung in a thick pall over everything, and it was impossible to see more than ten yards. In vain I looked for landmarks in the German line, to guide me to the right spot, but I could not see through the gas. Inevitably we scattered... Men were disorganised and walking in the direction of the German trenches, looking like ghouls in their gas helmets… We reached the German wire, only to find it intact… It would have been foolish to attack an unbroken front line with ten men, so we crawled away to the right, but in doing so I lost several men hit by machine gun fire which was sweeping between the lines… Suddenly I felt a sting in my right thigh and fell… I saw two holes in my breeches and took my pocket knife and ripped them up. I had a field dressing on me, so I bound up the wound. I now thought it was time I gave up trying to find my regiment, so I started to crawl back towards our lines.’

Letter from Second Lieutenant George Grossmith to his fiancée - 27 September 1915

The Cameron Highlanders in the Hohenzollen Redoubt at Loos, 25 September 1915

Lessons

The battles of 1915 showed both the Allies and the Germans how difficult it was to break through on the Western Front.

In most battles, the British and French had around a three-to-one superiority in men and artillery. But, although the German defenders gave ground, they did not break and were often able to retake some of their lost positions.

Both side drew lessons from this, the results of which would be demonstrated in the huge attritional struggles of the following year.