Occupation

In the aftermath of the Second World War (1939-45), there was a clear plan for how to deal with a defeated Germany. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery had talked about winning the peace in May 1945; now was the time to do it.

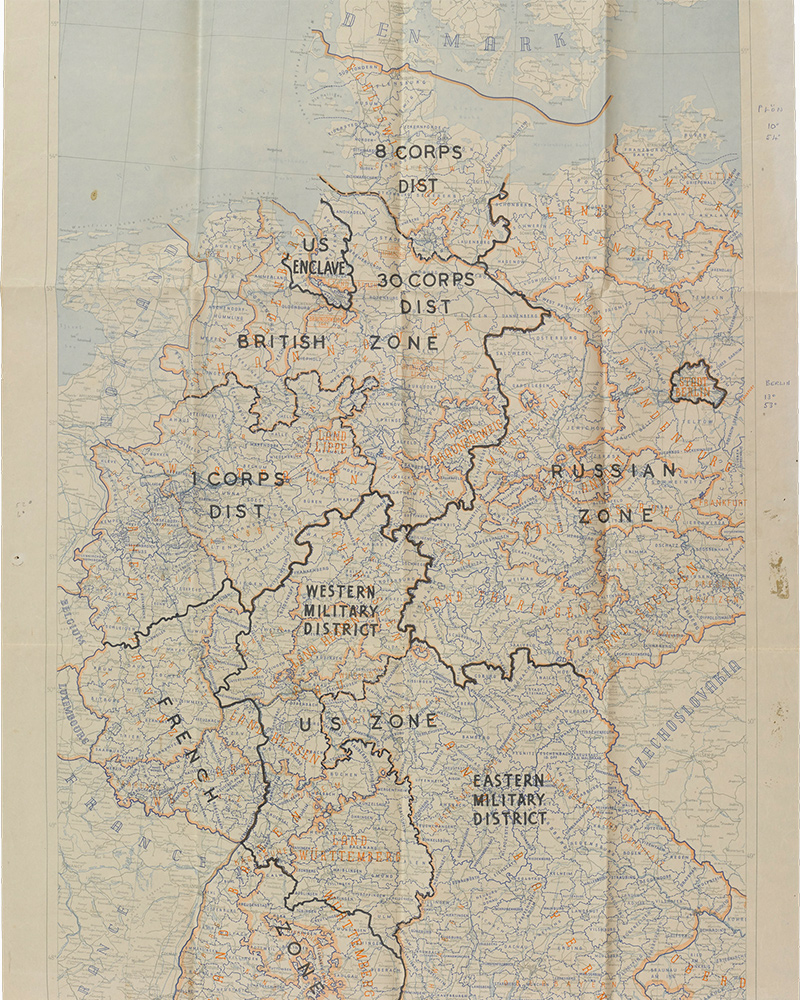

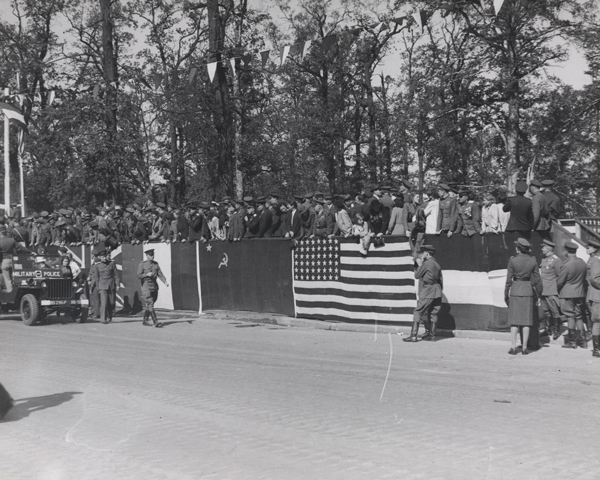

At Yalta in February 1945 the Allies had decided that Germany would be divided into four occupation zones, with each of the victorious powers taking responsibility in their zone. This structure was established by the Berlin Declaration on 5 June 1945, which pronounced the end of the Third Reich and the replacement of all German civic and political authority by that of the Allies.

The Allies would be the sole political and legal authority in the defeated Germany. The Potsdam Conference in July-August 1945 later formalised their goals. These insisted that Germany be demilitarised and that de-Nazification take place. The conference also confirmed the zones of occupation and the joint administration of Berlin. The Allies would work together in the Berlin-based Allied Control Council, constituted on 30 August 1945, which would oversee matters relating to the country as a whole.

In a matter of weeks, the British had moved from conquerors to occupiers and governors. To facilitate this, the conquering forces quickly evolved; 21st Army Group was dissolved in August 1945 and became the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), with an administrative rather than a military role. It was headquartered in the spa town of Bad Oeynhausen in North Rhine-Westphalia. But it was not long before war loomed once again on the horizon.

Allies become enemies

The British had ended the Second World War on strained terms with some of their allies. It did not take long for the ideological differences between them, that had been put aside during wartime, to re-emerge. The main area of tension was about Germany's future.

In March 1948, the Soviets withdrew from the Allied Control Council after learning of Allied proposals to create a new West German state. With the main body for cooperation and partnership paralysed, and relations non-existent, a confrontation between the former Allies seemed inevitable.

On 24 June 1948, following increased tension and agitation, the Soviets exploited Berlin’s location deep inside the Soviet Zone and blockaded the city.

Airlift

The Western Allies responded. On 26 June 1948, the Berlin Airlift, a mission to supply the city by air, commenced. On 12 May 1949, the Soviets lifted the blockade of West Berlin and the phenomenal operation was drawn to a close the following month.

During the 13 months from 26 June 1948 until 1 August 1949, more than 266,600 flights, carrying over 2,223,000 tons of food, fuel and supplies, were made to Berlin by British and US aircraft. At its peak, one plane landed every minute at either Tempelhof, Gatow or Tegel.

Even flying boats were used, which landed in the Havel See, and were then unloaded by barges. The Allies had estimated that 4,500 tons of supplies were required per day to keep the garrisons and civilians fed, clothed and heated. In the end, they had managed an average daily rate of 5,579 tons.

Despite the success of the airlift, the Allies were so alarmed by the Soviet actions that they decided the only answer was collective defence. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) was therefore formed in April 1949.

Two blocs emerge

In May 1949, the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

In May 1955, West Germany joined Nato. In response, the Communist states of Eastern Europe formed the Warsaw Pact under Soviet tutelage.

With ideological battle lines drawn between East and West, Europe was now locked into the Cold War. The BAOR and its Nato allies became responsible for Western Europe’s defence, with the forces in West Germany now on the front line.

As well as the threat of an all-out Warsaw Pact assault on the West, the troops in Germany also faced the prospect of nuclear attack, as atomic weapons added to the tension and risk.

‘I believe that we are committed to war with the Russians eventually.’General Brian Robertson, Military Governor of the British Zone in Germany — September 1948

The next war

The Cold War set the tone for soldiers’ lives in Germany for the next 40 years. From the 1950s, the nuclear element was increasingly factored into British planning. As General Sir Richard Gale, Commander-in-Chief BAOR, said in September 1955: ‘The dominant factor is becoming the nuclear factor.’

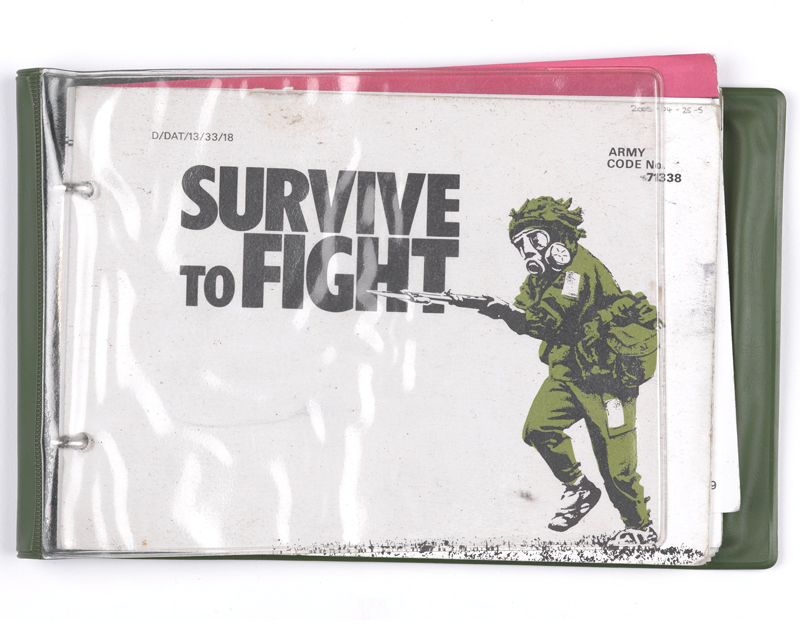

The British had their own nuclear weapons with which they would counter any Soviet move. Soldiers prepared by incorporating nuclear weapons into training and operating practices. They were trained to protect themselves from any nuclear, biological or chemical (NBC) attacks. This included learning drills to prepare for a potential attack and how to remain an effective fighting force. These drills were known as ‘Survive to Fight’.

Manpower

In 1949, as a result of the Berlin Airlift, the BAOR's manpower was set between 53,000 and 55,000 soldiers. It was also returned to a war fighting role. It was this force that would actively confront the rising Soviet threat, staring them down across the increasingly fortified Inner German Border, or across the walls and wire of divided Berlin.

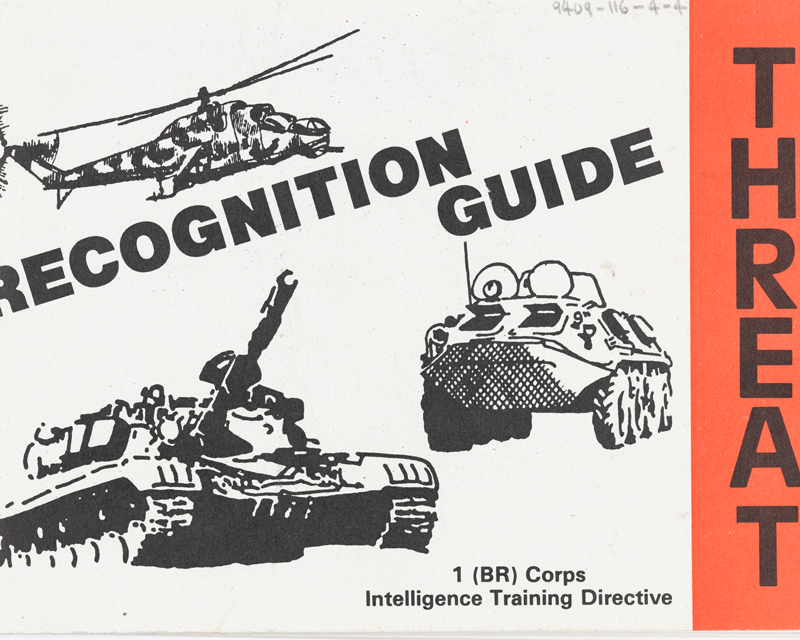

The looming threat of the Soviet forces massed across the Inner German Border were the principal enemy for which the Army prepared. Outnumbered three to one, any battle would be short and bloody. Everything about life in the BAOR was geared towards fighting and winning. It was about preparing not just for a war, but the war.

Active Edge

Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the British were able to maintain effective deterrence in Germany by focusing on perfecting their skills and drills through relentless, rigorous training at all levels. From small-unit training, to large scale exercises, the British trained constantly.

The call of the codeword 'Active Edge' would begin the exercise that tested a unit’s ability to mobilise and deploy within hours to their positions in readiness for a Soviet attack. Soldiers were expected to be capable and ready at a moment’s notice. When 'Active Edge' was called, it wasn’t always clear whether it was a training exercise or the real thing.

Intelligence on the enemy was also key. Threat recognition guides were produced and regularly updated to tell British soldiers what to expect from the Soviets, and what weaknesses their equipment had. At the same time, handbooks were produced to help British soldiers recognise friendly and allied equipment when on training exercises, so that when the time came in the heat of battle they could distinguish between friend and foe.

Lionheart

During the 1980s, under the leadership of Lieutenant General Nigel Bagnall, the BAOR developed its tactics to include a counter-attack phase - raising confidence not only about being able to stand and fight should the Warsaw Pact attack, but ultimately win any potential conflict through hard-hitting, mobile operations.

Large-scale Autumn exercises had already become an annual occurrence for the British. The biggest of these, in fact the largest exercise ever put on by the Army, was 'Exercise Lionheart', which took place between 3 September and 5 October 1984. It took four years of planning, and cost around £31 million (over £100 million in today’s money). The event was also attended by hundreds of foreign and Commonwealth military observers.

Around 130,000 UK troops descended on the British Zone to rehearse and test their wartime plans. It was an exercise that defined an entire era, but it was absolutely necessary if the British were going to fight and win in West Germany.

Brixmis

Formed in 1946, the British Commanders'-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany (or Brixmis), was created to enable closer working relations and better communication with the BAOR’s wartime Soviet allies as both sides set about administrating occupied Germany.

It was based in the British Army’s West Berlin headquarters, and in a villa in Potsdam, inside the Soviet Zone. There was a Soviet equivalent, based in the British Zone of West Germany, called Soxmis.

Intelligence

Even as relations between the Western Allies and Soviets descended into distrust and conflict, the missions were retained. The formal, social liaison duties continued with hosted visits, garden parties and cocktail receptions. But there was also an unprecedented opportunity to gather intelligence on Warsaw Pact forces and their equipment in East Germany.

Three-man groups from Brixmis would go on ‘tours’, operating behind enemy lines. Through infiltrating enemy facilities and observing their training and tactics, crucial information was passed back to the UK. Brixmis was a tiny part of the BAOR, usually only numbering around 30 officers and men, but it played a vital role during the Cold War.

Training area legend

British troops spent millions of hours during the Cold War honing their skills on the specialist training areas available to them in West Germany. These places all had their own reputations, and created their own stories, myths and legends: the stairs at Vogelsang, or the haunted buildings at Sennelager. But greatest of all was that of Wolfgang Meier on the Soltau-Lüneburg Training Area.

Wolfgang was an enterprising local German who sought to capitalise on the hungry British troops on the training area. For 25 years, his catering vans served bratwurst, fish and chips, chips with mayonnaise, and liquid refreshment to eager and grateful soldiers, who flocked to the van wherever and whenever it appeared.

With an uncanny ability to sniff out British troops despite their attempts at camouflage - so much so that it was jokingly suggested he might be a KGB spy - and navigate challenging terrain, Wolfgang was and remains a fixture of the British Army’s cultural memory in Germany.

PIRA

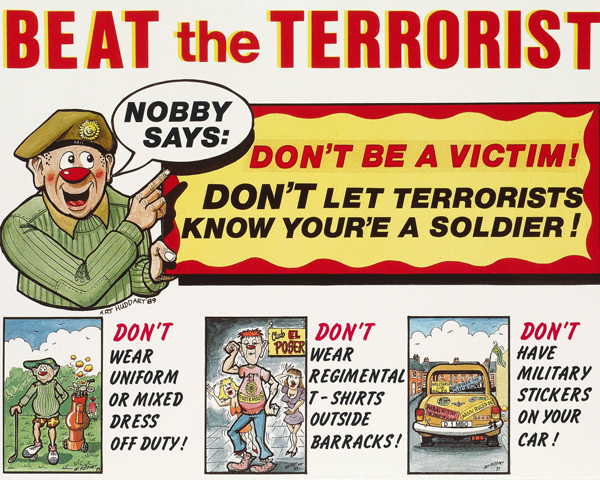

Despite the Cold War and the looming Soviet threat across the border, another enemy intruded into the lives of British soldiers, their families and their German neighbours. Although soldiers from Germany were deployed to Northern Ireland during 'the Troubles', the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) also began targeting the British in Germany from the 1970s. Bombings and shootings put soldiers and their families in real danger.

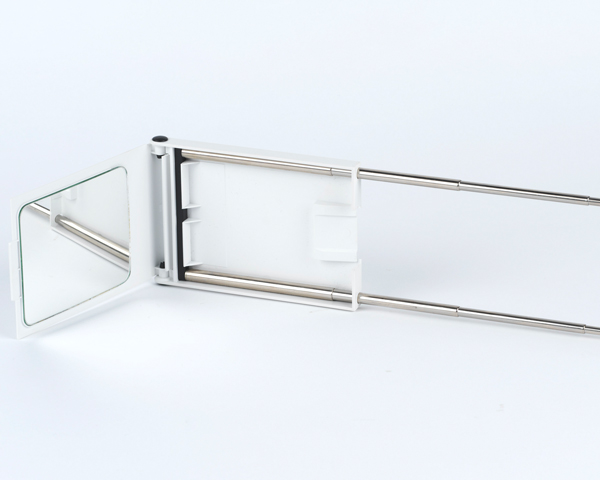

The British community developed a lifestyle of constant vigilance. They were encouraged in this by posters and leaflets. They were also issued with handheld mirrors to sweep under their cars to check for bombs. To better protect them, the distinctive British number plates on their cars were removed and replaced with German ones. This vigilance was well-founded; the IRA threat remained constant, and for many was more serious than that posed by the Soviets.

A British island

It was in West Berlin, deep inside Soviet-dominated East Germany, that British forces were at their most precarious during the Cold War. The establishment of the Berlin Wall in 1961, and the fortifying of the Inner German Border with wire and watchtowers by the Communists - Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ made real - created a new world of walls and wire for the British; a world complete with new rituals, duties, threats and opportunities.

The British military presence in Berlin comprised 3,100 men in three infantry battalions, an independent armoured squadron, and a number of support units. The three infantry battalions were rotated every two years, and the armoured squadron was detached from a BAOR armoured regiment based in West Germany. British West Berlin was truly an island in a Communist sea.

Posting

Throughout the Army’s time in Cold War Germany, West Berlin was seen as the most exciting posting available. With lavish facilities built around the 1936 Olympic Stadium, good quarters, excellent food - all paid for by the West Berliners - and a young and vibrant metropolis to be explored, Berlin offered soldiers many opportunities. The presence of the Soviets - and, from 1961, the Wall - added to the atmosphere.

The distinct rituals and duties involved in serving in Berlin and the tension of operating near the Wall all created a unique environment, both on and off duty.

Train

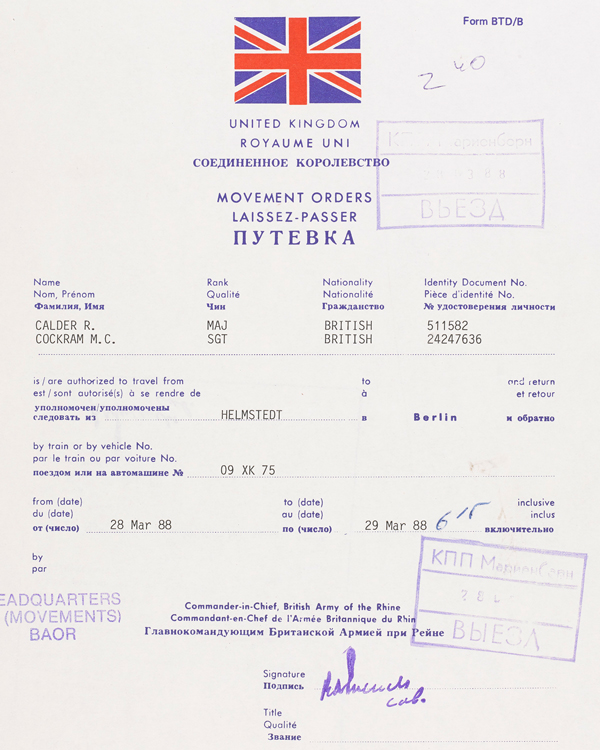

With Berlin located deep inside the Soviet Zone of Germany, access to the city was heavily controlled. All movement had to be reported and authorised by the Soviets. Those driving from the British Zone could only cross at Checkpoint Alpha, the Helmstedt-Marienborn crossing, and the journey to West Berlin had to follow a set route and be completed in a set time.

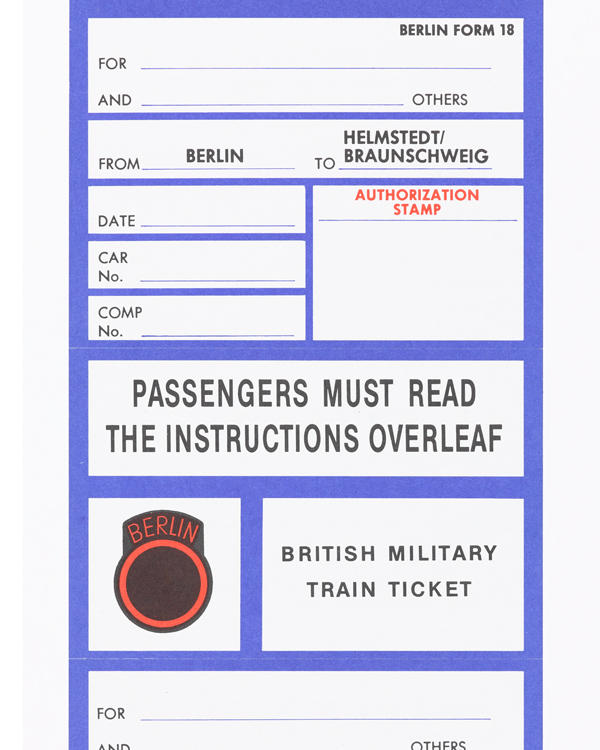

Another route was via train. From 1945 to 1991, the Berliner train from Charlottenburg in West Berlin to Braunschweig in the British Zone of West Germany ran every day, apart from Christmas Day and during the short interlude of the Berlin Blockade. It was operated by 62 Transport and Movement Squadron, Royal Corps of Transport.

Out of uniform

While Army life in Germany was dominated by training for the expected confrontation, with strict minimum-manning requirements that governed issues like leave, there were opportunities to enjoy life when off-duty. For those stationed in Berlin, there were the undoubted attractions of city life.

Amusement could be found in West Berlin and around the British sector in neighbourhoods like Charlottenburg - 'Mon Cheri' in ‘Grotty Charlotty’ has its own reputation - but also on trips to the East, where the exchange rate favoured the British.

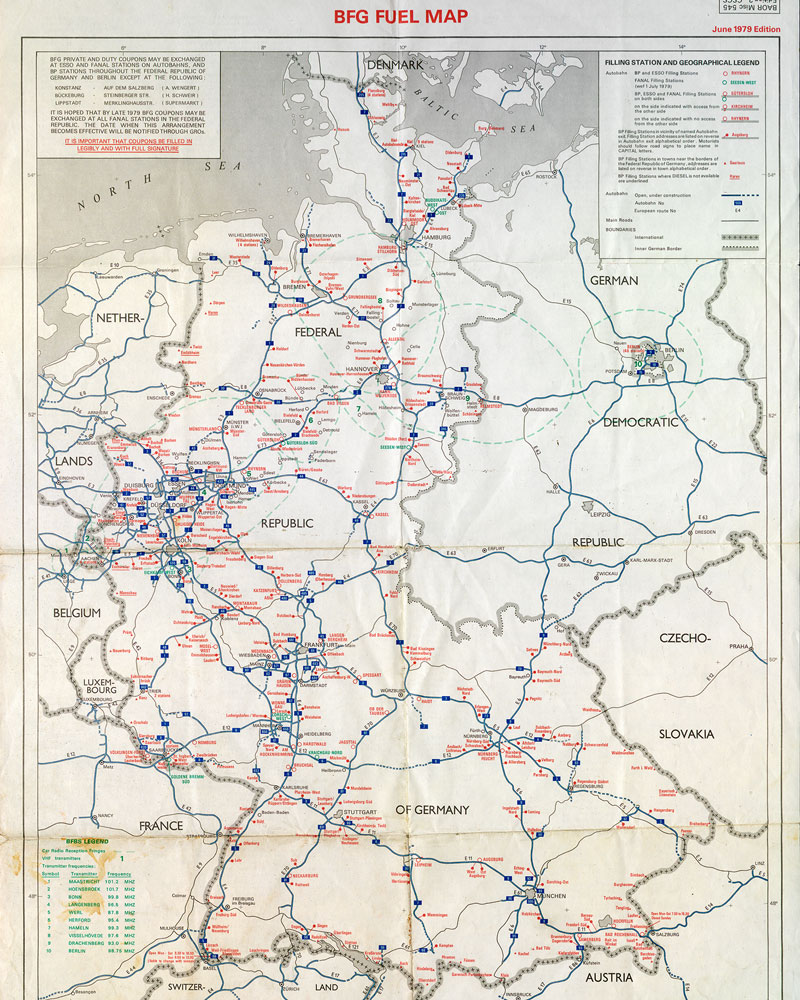

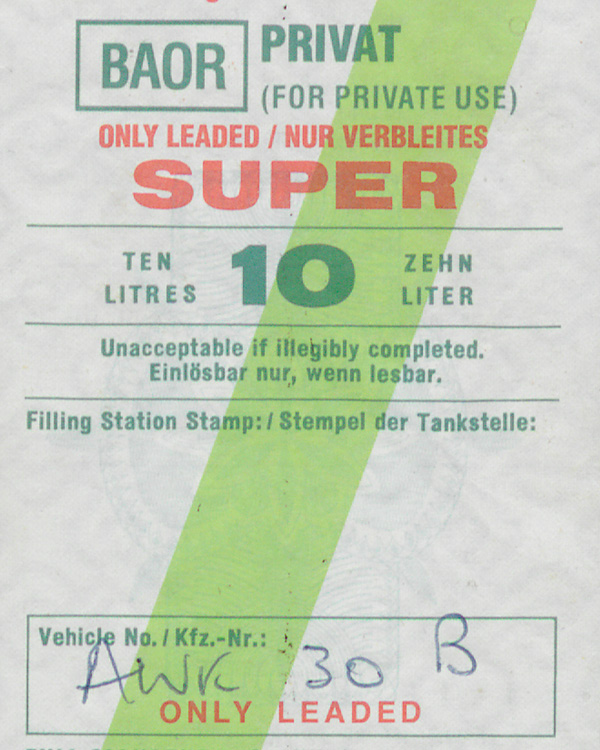

In other towns, there were plenty of attractions, including local beers like Herforder Pils. But life could be hard for those in rural areas, where the strength of the garrison community was key to making sure soldiers and their families were happy. The opportunity to travel around Germany was something many soldiers and their families took, making good use of the tax-free petrol they received.

Sport

Another popular pastime for British forces in Germany was sport. The sports on offer included those available elsewhere in the Army and the UK, such as football, rugby and polo - increasingly also played against local German teams. But there were also pastimes that were more dependent on service in Germany. Adventure training was common across the Army, but in Germany there were fantastic facilities, such as those at the Kiel Yacht Club, or the Möhnesee Sailing Club.

Opportunities unavailable to soldiers elsewhere included skiing in the Harz Mountains or Bavaria. Indeed, thousands of soldiers would descend on Bavaria each year for Exercise Snow Queen, with many staying in ski huts owned by their regiments.

‘There was also a thought of, What now? What are we here for? What’s going to happen to us here in Germany now that all this is coming to an end? What is the purpose of British Forces Germany?'Corporal Jim Toms, The Royal Corps of Signals — 1983-1998

After the fall

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 heralded a rapid change in the established world order. In quick succession, the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact collapsed, led by Poland and Hungary breaking away and establishing democracy. The British forces in Germany, which had stood on the front line of the Cold War in Europe, had accomplished their task.

But as the Cold War ended, questions were asked about the BAOR's future. What was the role of the Army in Germany now that the major threat had been defeated? The following decades would see the size, structure and role of the Army transform, with huge impacts on soldiers and their families, and on the relationship between the Army and Germany.

The BAOR was formally disbanded in 1994. The remaining troops became part of the multi-national Allied Command Europe Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC), which was under British leadership.

Germany became a launchpad for the Army, from where it could deploy around the world, to places like the Gulf in 1990-91 and Iraq in 2003. Soldiers from the German garrison also completed the last combat tour in Afghanistan in 2014.

In 2010, the Strategic Defence and Security Review made further cuts in the German garrison. It was also announced that the majority of soldiers would leave the country by 2020.