Trumpet banner on display in the Amy at Home gallery

Ceremonial role

The Army’s involvement in public ceremonies has helped foster a sense of nationhood and continues to bring people together today. This ceremonial role has been particularly conspicuous in recent years, drawing global attention during the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II and the coronation of King Charles III.

Military bands are a prominent feature of all such occasions. Although bugles, trumpets, pipes and drums were originally used for battlefield communication, military music has become an important part of both the Army's and the nation’s ceremonial traditions.

State Trumpeter's coat, 1911

State Trumpeters

The Army at Home gallery features a State Trumpeter's coat dating from 1911. This is an example of State Dress, the oldest continually worn uniform in the British Army. Introduced in the 1600s, it is still worn by trumpeters and bandsmen of the Household Cavalry when parading in the presence of senior members of the Royal Family or the Lord Mayor of London.

The gallery also features a newly conserved trumpet banner. Banners like this were attached to the instruments that State Trumpeters used to sound fanfares at ceremonial events. A Household Cavalry herald's trumpet hangs alongside it.

Trumpet banner

The trumpet banner on display is a sealed pattern from around 1910, the first year of King George V’s reign. It would have been sent out to manufacturers, who could then use it for quality assurance purposes.

Fringed with gold thread, it bears the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom. At the centre, the symbols on the quartered shield represent the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. Either side of the shield stand the lion of England and the unicorn of Scotland.

Angels are situated above the coat of arms, facing towards the crown and cipher of George V. The corners of the banner are embroidered with roses, thistles and shamrocks, also symbols of the three unified kingdoms.

The banner before the conservation work

The banner after the conservation work

Loose threads

Before going on display, the banner required extensive conservation work. In many places, gold and silver passing thread was coming loose. The gold fringe was starting to detach at points and had become tangled with stray threads. The unicorn was also missing an eye.

First, each section of fringe was ‘combed’ to release tangled coloured thread and debris. All coloured threads were retained for their historical significance; these were probably materials used in the busy workrooms of companies that manufactured banners.

A section of tangled fringe before 'combing'

A section of untangled fringe after 'combing'

Wear and tear

The crimson damask silk at the front of the banner was in fair condition, but the blue silk lining had numerous signs of wear and tear. To support these areas, silk was dyed to match the original colour. This was then placed underneath and secured with laid couching stitches.

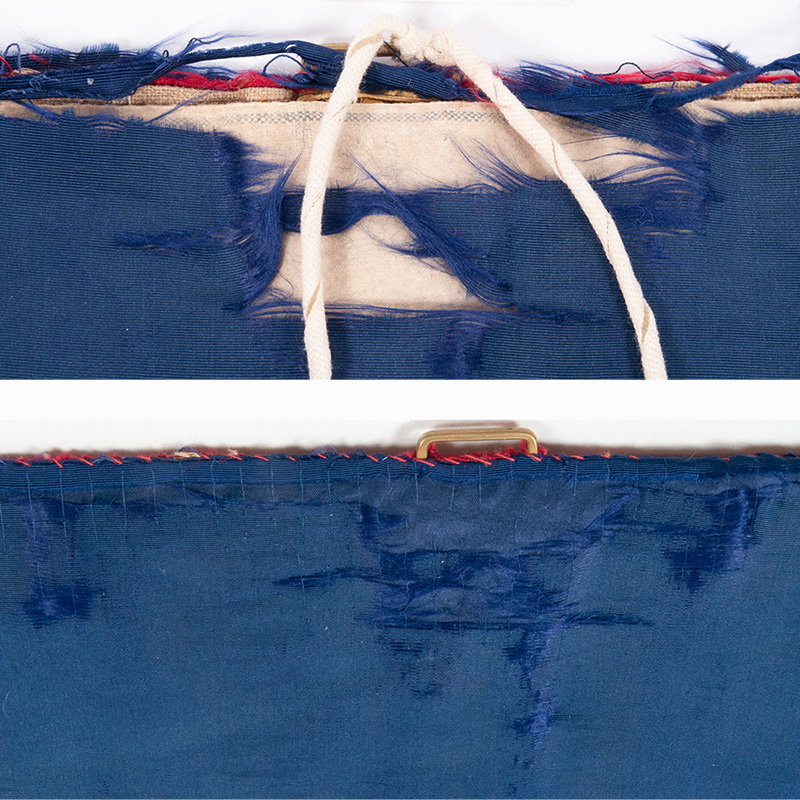

The blue silk lining before treatment (top) and after treatment (bottom)

Distinct stitches

The images below show an area where the silver passing thread was coming loose. It was secured back in place using a laid couching stitch, just as the original maker would have used.

Conservation work must be sympathetic, but should also remain detectable, at least to another conservator. With this in mind, a light grey thread was used instead of the original white. This allows anyone looking closely to distinguish the new stitches from the old.

Example of silver passing thread coming loose

Repairs made using a distinct light grey thread

An eye for an eye

The final thing to consider was the unicorn's missing eye. After discussion with the curatorial team, it was decided that a replica conservation-grade eye should be made, similar in size, shape and colour to the still-intact glass eyes of the lion.

The unicorn with its newly made replica eye

See it on display

You can see the results of this painstaking conservation work in our Army at Home gallery, along with other items that highlight the significance of the Army’s ceremonial role.