Background

Allied leaders agreed that establishing a second front in North West Europe, and relieving the pressure on the Russians on the Eastern Front, was essential in order to defeat Nazi Germany during the Second World War.

They chose Normandy as the location for the D-Day landings, despite the Calais area offering a much shorter Channel crossing. Normandy had excellent landing beaches, was less fortified than Calais and was still within fighter aircraft range.

‘This operation is planned as a victory, and that’s the way it’s going to be. We're going down there, and we’re throwing everything we have into it, and we're going to make it a success.’General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe — 1944

Deception

The Allies put in place elaborate deception plans to convince the enemy that the main landing would be in Calais. Their aim was to reduce the flow of German reinforcements into Normandy.

These plans included double agents spreading false information, heavy bombing of the Calais area and a dummy 'army' being set up in eastern England.

Planning

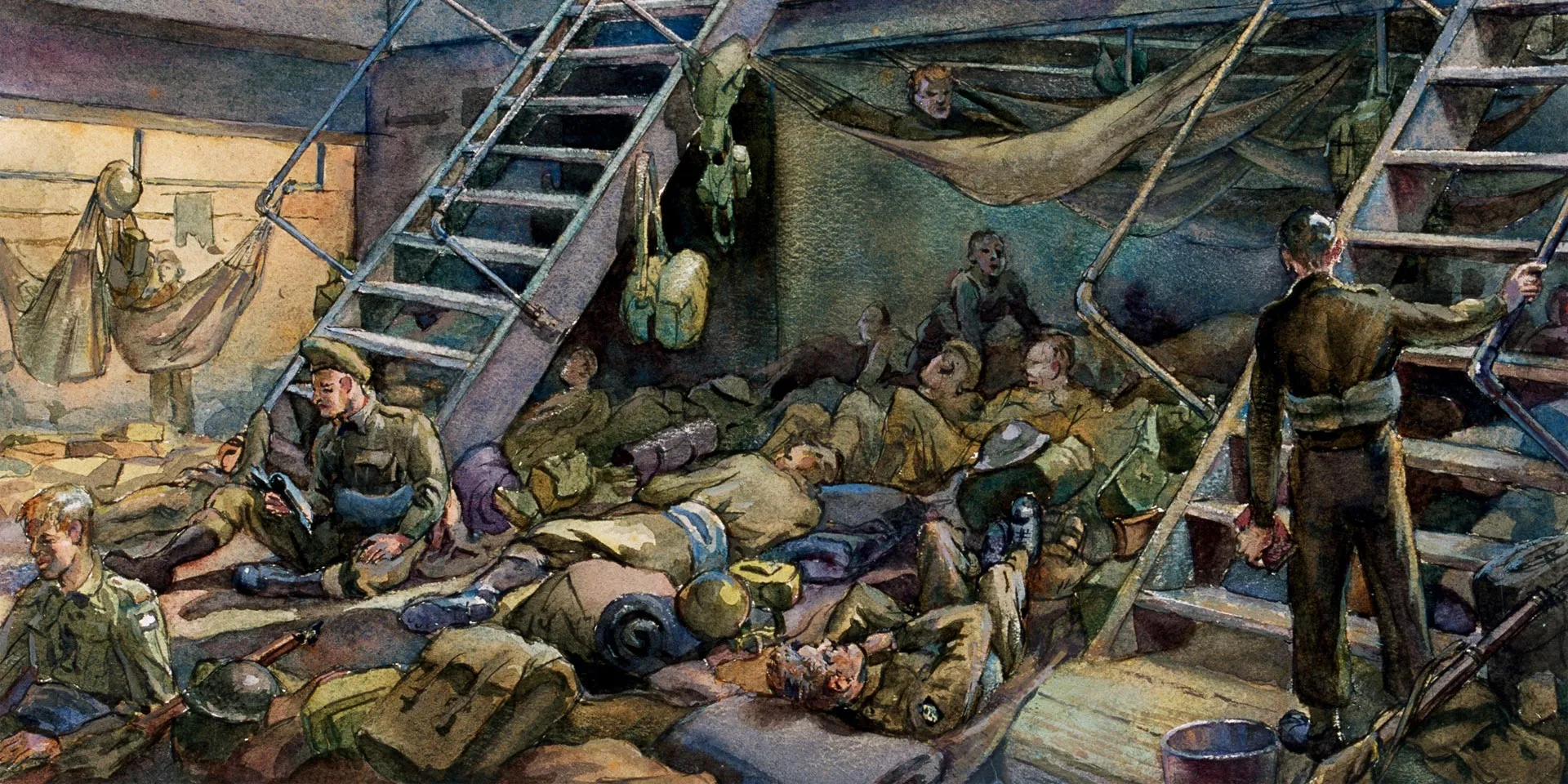

Extensive training took place in the UK in the months leading up to D-Day, ranging from divisional exercises to individual training to prepare soldiers for the assault. At the same time, a huge build-up of materiel took place, with the south of England beginning to resemble a huge military camp packed with vehicles, tanks, supplies and soldiers from many nations.

Thousands of air reconnaissance photographs of the German defences were taken. Special forces teams landed on the coast to gather information. Others worked with the French resistance to gather intelligence on German troop dispositions and carry out acts of sabotage against transport and communication networks.

Allied command

The Supreme Allied Command was established to manage the multi-national force bound for Normandy. US General Dwight Eisenhower was Supreme Commander. He oversaw all air, land and sea units involved.

Eisenhower was ultimately responsible for planning and supervising the invasion. British General Bernard Montgomery commanded all the land forces taking part, around 160,000 men.

5 June / 5.00pm

Operation Neptune

5 June / 10.00pm

To the air

6 June / Midnight

Green means go

6 June / 2.00am

Bombs away

6 June / 5.23am

Open fire

6 June / 6.30am

H-Hour

Beaches

A fleet of over 5,000 ships and landing craft crossed the Channel. Heavy bombing, along with a massive naval bombardment, destroyed many of the German defences. Assault troops then landed on five beaches.

Airborne forces were dropped behind the beaches and on their flanks to slow down German counter-attacks. Bridges, road crossings and coastal batteries were seized to help the amphibious forces advance inland.

To maintain secrecy, the beaches were given codenames: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword.

Map of the Normandy landing beaches, France, 1944

Invasion

The US Army was the western invasion force, landing on Utah and Omaha beaches. Omaha was the most heavily defended of all five beaches and the Americans suffered high casualties there during the invasion.

The eastern invasion force was made up of British troops, landing at Gold and Sword beaches, and the Canadians, landing at Juno. These beaches were closer to Caen, which the Allies were planning to liberate.

The British met with relatively weak defences and succeeded in meeting up with the paratroopers dropped earlier. This was not the case for the Canadians at Juno. The heavily fortified defences and rough seas meant that they too suffered many losses.

The Americans named their invasion beaches after places in the US, while the British chose words from an Army pamphlet. All of the codenames were chosen for their clarity when communicating by radio.

Impact

The Allies' deception plans had worked brilliantly. The destination of the landings remained a secret and the Germans were convinced that a second, larger attack would take place elsewhere. Much-needed German troops were held back in other regions awaiting an invasion that never took place.

The initial German response was slow and poorly co-ordinated. The generals couldn't move their armoured reserves without Hitler's approval.

The Allies suffered at least 10,000 casualties on 6 June 1944, ten times the number of German losses. And many of the immediate strategic objectives of the landings were not achieved, including the failure to capture any of the key towns.

But D-Day was still a huge success. More than 160,000 Allied troops and 6,000 vehicles had crossed the Channel and established a foothold in France. Their task now was to drive the Germans into retreat.

Utah

Lost: 200 / Landed: 23,000

Omaha

Lost: 3,000 / Landed: 32,000

Gold

Lost: 450 / Landed: 25,000

Juno

Lost: 1,000 / Landed: 21,000

Sword

Lost: 650 / Landed: 29,000