Major Herbert 'Blondie' Hasler and a colleague paddling a canoe, c1942 (

© Trustees of the National Museum of the Royal Navy )

Early life

Herbert George Hasler was born in Dublin in 1914. His father, an officer with the Royal Army Medical Corps, drowned when the British troopship 'Transylvania' was torpedoed and sunk in 1917. After this, Herbert and his older brother were raised by their mother in Portsmouth.

Hasler’s passion for sailing and craftsmanship started at an early age. As a boy, he built his own canoe, using instructions from an issue of 'Boy’s Own Paper', and took it out on excursions around Portsmouth Harbour and the Isle of Wight.

He was also a conscientious student. He won a scholarship to Wellington College, where he excelled in his studies and at sports.

Royal Marines

Immediately on leaving school in 1932, Hasler was commissioned into the Royal Marines. His work ethic and enthusiasm again paid dividends as he passed out top of his year.

Soon after joining the Marines, he grew a splendid blonde moustache, from which he acquired his nickname ‘Blondie'.

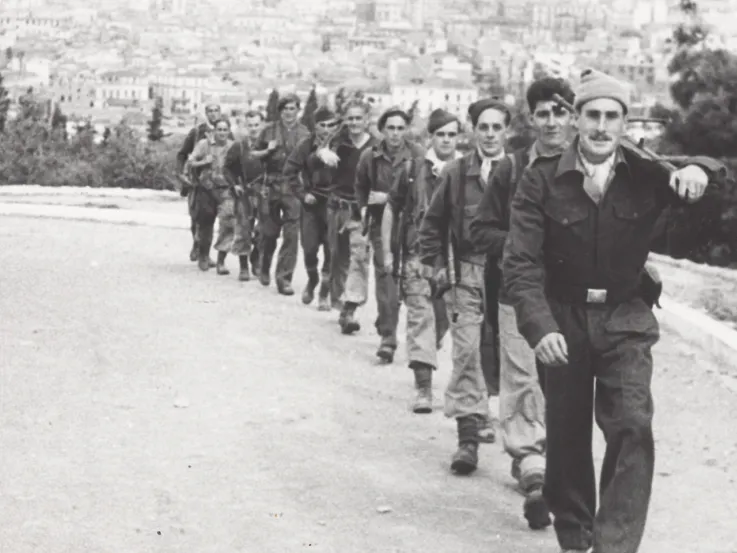

Major Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler, c1942 (© Trustees of the National Museum of the Royal Navy)

A unique character

Hasler was a formidable character. Creative and intelligent, he cultivated a wide range of interests and skills: from craft, design and mechanics to art, music and writing. He was also tough, taking pains to develop his fortitude by setting himself a series of exacting, if sometimes bizarre, physical challenges.

Private and introverted, Hasler came across as an eccentric loner to some of his comrades. But this belied his great professionalism and his indomitable will.

Hasler would draw upon all these qualities during his service in the Second World War (1939-45). He saw action early on during the Norway campaign of 1940, as a result of which he was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

Sea raids

In early 1941, Hasler submitted a paper to the Admiralty on the idea of attacking enemy ships in harbour using collapsible canoes, known as folboats. Similar ideas were already being pioneered by special forces officers like Captain Roger Courtney, who had set up the Special Boat Section to carry out canoe raids and reconnaissance.

In December 1941, Italian special forces struck at the British fleet in Alexandria harbour, Egypt. Using motorised ‘human torpedoes’, the Italians succeeded in penetrating the harbour defences and crippling HMS 'Elizabeth' and HMS 'Valiant'.

The British realised that the Italians had stolen a march on them in this novel and technical form of war.

Hasler’s paper now came to the attention of the staff at Combined Operations Headquarters. He was asked to join the Combined Operations Development Unit, tasked with developing new methods and vehicles for amphibious attack.

Cockle Mk II of the type used in Operation Frankton, c1943 (© IWM (MAR 583))

RMBPD

Hasler's remit was wide ranging, but he remained convinced that canoes presented the best method of attack. In May 1942, he obtained permission to set up his own special force of canoeists. To disguise its true purpose, it was named the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment (RMBPD).

In September, after several months of intense training, Hasler’s unit was given its first mission. Codenamed Operation Frankton, it was a raid against the German-occupied port of Bordeaux in France.

Operation Frankton report showing the route taken by cockles ‘Catfish’ and ‘Crayfish’, 1943 (© Trustees of the National Museum of the Royal Navy )

Bordeaux raid

Bordeaux was the hub of Germany’s trade with the Far East. From here, German merchant ships evaded the British naval blockade and brought in valuable raw materials like rubber, tin and tungsten, which were important for the German war economy. Snuffing out this trade by blowing up enemy merchant ships would deal Germany a severe blow.

The plan was for six two-man canoe teams of the RMBDP to be deployed by submarine into the sea near the mouth of the River Gironde. Travelling by stages at night, they would paddle 90 miles (145km) through the estuary and upriver to Bordeaux, a journey of several days. Here they would attach magnetic ‘limpet’ mines to the hulls of merchantmen below the waterline, before making their escape overland via Spain.

To accomplish this, the RMBDP would be equipped with the Cockle Mk II collapsible canoe, designed to Hasler’s specifications. This canoe would give its name to the men who took part in the raid, the ‘Cockleshell Heroes’.

Limpet mine of the type used in Operation Frankton, c1944 (© The Combined Services Museum)

Ampoules for limpet mines used on Operation Frankton, c1944 (© The Combined Services Museum)

Losses

The operation took place on 7 December 1942 and things went wrong immediately. One of the canoes was damaged as it was taken out of the submarine and could not take part. Worse, their training for getting through the powerful tidal forces at the mouth of the Gironde was inadequate, and one canoe capsized. Despite efforts to tow the capsized men close to shore, they both died at sea.

More tragedy was to follow in the coming days as two teams were captured by the Germans. They were later executed in accordance with Hitler’s notorious ‘Commando Order’, which stated that any soldiers captured behind the lines would be executed irrespective of whether they were in uniform. Many members of Britain’s special forces would meet a similar fate as the war progressed.

Enduring cold and fatigue, the two remaining crews manged to get through to Bordeaux after five nights’ hard paddling. They succeeded in placing limpet mines on six ships before escaping.

Escape

Two more men were soon caught by the Germans and executed. Only Hasler and his comrade Bill Sparks succeeded in getting away, making their way back to Britain via Spain; an epic journey of four months.

Hasler was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his exceptional courage and leadership. The raid was heralded as a success and was a great boost to British morale.

'Of the many brave and dashing raids carried out by the men of Combined Operations Command none was more courageous or imaginative than Operation Frankton.’Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten

Impact

However, the military value of the raid has been called into question. Many of the damaged ships were repaired and brought back into service, and the impact on Germany’s Far Eastern trade was minimal.

Moreover, it was later discovered that the Special Operations Executive (SOE) were planning their own attack on Bordeaux harbour at the time. Their mission - which may well have been completed with less cost to human life - was aborted in the wake of the Cockleshell raid. This was a damning indictment of Combined Operations and SOE’s failure to co-ordinate their work.

Inventions

Following the raid, Hasler returned to working on new methods of infiltration and attack. This included the use of experimental craft like the ‘Sleeping Beauty’, a submersible canoe. Another was the ‘Chariot’, a British version of the human torpedo. While highly inventive, none of these were to prove particularly useful militarily.

From 1944, he served as part of a special forces unit in the Far East. After the war, the RMBPD was incorporated into what became the Special Boat Service.

After leaving the Royal Marines in 1948, Hasler continued to pursue his passions for sailing and inventing, notably developing a mechanism - still widely used today - that allows yachts to be sailed single-handed. He also took part in numerous sailing contests and founded the Observer Single-handed Transatlantic Race from Plymouth to New York.

In 1965, Hasler married Bridget Fisher, also a keen sailor. He died in Glasgow in 1987.