Borneo

In 1962, northern Borneo consisted of the British protectorate of Brunei and the colonies of Sarawak and North Borneo (later known as Sabah). The rest of the island was made up of the Indonesian provinces of Kalimantan.

Britain hoped to incorporate Brunei, Sarawak and North Borneo - all close to independence at that time - into the Federation of Malaysia, along with Singapore and the states of the Malayan Peninsula.

However, President Sukarno of Indonesia was wary of continued British influence in the region. He wanted to extend Indonesian control on the island by adding these territories to the rest of Kalimantan.

Map of the island of Borneo, 1962

Brunei revolt

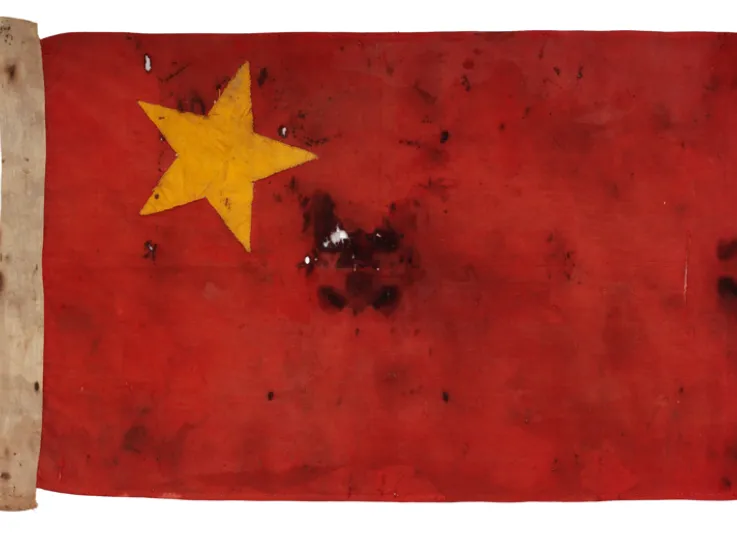

On 8 December 1962, pro-Sukarno rebels, known as the North Kalimantan National Army, tried to capture the Sultan of Brunei who called on the British for help.

Within hours, two companies of Gurkhas had been airlifted in from Singapore. Over the next few days, other units joined them, including the Queen's Own Highlanders and 42 Royal Marine Commando.

After rescuing a number of hostages and securing Brunei's key strategic points - such as its radio stations, government buildings and oil refineries - the rebellion was easily suppressed.

North Borneo

In April 1963, hoping to intimidate the local population, Sukarno authorised cross-border incursions into North Borneo by so-called volunteers. Five battalions of British and Gurkha troops, under the command of Major-General Walter Walker, were committed to defend a frontier that extended for nearly 1,000 miles of jungle-covered mountain.

Soldiers at Nanga Gaat on the Rejang River, Sarawak, Borneo, 1964

Jungle warfare

Walker had experience fighting the Japanese in Burma and the Communists in Malaya, and he was quick to put the lessons learned in those campaigns into effect.

A keen advocate of the use of helicopters in modern military operations, he set out to dominate the jungle by patrolling and placed great emphasis on the gathering of intelligence.

Medical and agricultural projects were initiated to win the ‘hearts and minds’ of the local population. Locals were also recruited into an irregular force known as the Border Scouts.

Border raids

In September 1963, Sukarno committed Indonesian regular troops to the conflict. Their tactics were to cross the frontier in bodies of up to 200 men and establish bases in the jungle.

Walker responded by setting up bases of his own near the border, which were supplied and reinforced by helicopter. He also received permission to mount secret cross-border raids into Kalimantan to pre-empt Indonesian attacks.

Commonwealth effort

By the time Walker handed over command to Major-General George Lea, his force had been increased to 13 battalions of infantry, the equivalent of a battalion of SAS, plus artillery and engineer support.

Troops were provided by Malaysia, Australia and New Zealand as well as Britain. All eight battalions of Gurkhas were engaged in the confrontation and once again showed their value as jungle fighters.

‘When the House thinks of the tragedy that could have fallen on a whole corner of a continent if we had not been able to hold the situation and bring it to a successful termination, it will appreciate that in the history books [winning the conflict] will be regarded as one of the most efficient uses of military force in the history of the world.’Secretary of State for Defence Denis Healey addressing Parliament — 1967

End of conflict

By late 1965, the Indonesians had lost control of the frontier. They were further undermined by internal strife.

In October, the Indonesian army crushed an attempted coup by the Indonesian Communist Party, the main supporters of Sukarno. The following March, the anti-Communist General Suharto overthrew Sukarno. He then withdrew Indonesian forces from the border areas and signed a treaty with Malaysia in August 1966.

The confrontation was over. It had claimed the lives of 114 Commonwealth personnel and wounded another 180. Nevertheless, it had been a striking success for Britain’s new all-professional army.

General Service Medal with Borneo clasp awarded to Rifleman Topbahadur Mall, 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles