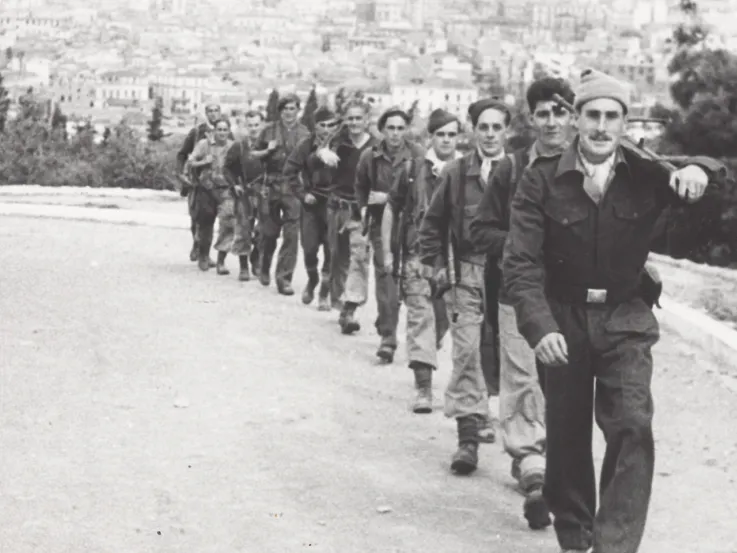

Special Air Service troops preparing to abseil from the roof of the Iranian Embassy, 5 May 1980 (© Combined Military Services Museum, Maldon, Essex)

Hostage-takers

At 11.30am on 30 April 1980, six armed members of the Democratic Revolutionary Front for the Liberation of Arabistan (DRFLA) stormed the Iranian Embassy on Princes Gate in South Kensington, London, taking 26 people hostage.

The DRFLA had been involved in an Arab uprising in the southern Iranian province of Khuzestan following the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The group was still fighting for that region’s autonomy and seeking the release of prisoners captured during the rebellion.

Six days of tense dialogue with the Metropolitan Police negotiators began. The operation was directed by a team comprising the Metropolitan Police Deputy Assistant Commissioner John Dellow, Home Office Assistant Secretary Hayden Phillips, and Lieutenant Colonel Michael Rose, commanding officer of the Special Air Service (SAS), the British Army's primary anti-terrorist unit.

Until that time, the SAS was almost completely unknown to the general British public. But that was about to change.

Domestic counter-terrorism

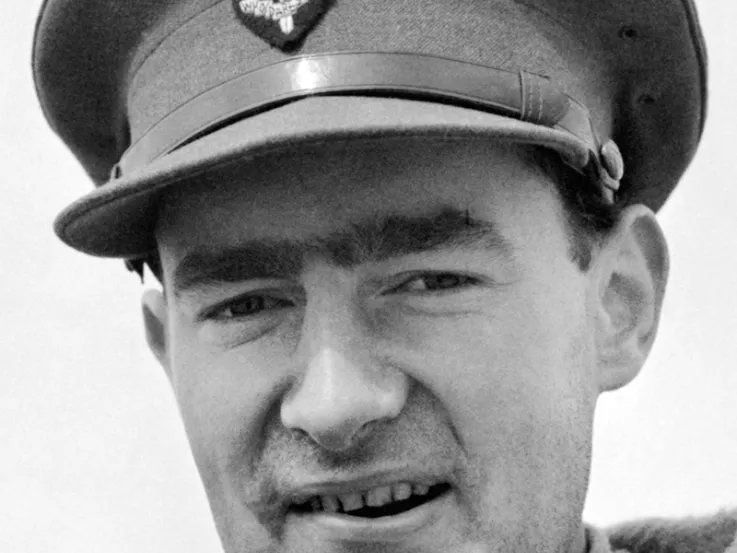

Interviewed in 2015, former SAS commander General Sir Peter de la Billière outlines how the unit's domestic counter-terrorism role had been established prior to the 1980 siege.

30 April 1980

30 April 1980

30 April 1980

30 April 1980

1 May 1980

1 May 1980

2 May 1980

2 May 1980

3 May 1980

3 May 1980

5 May 1980

5 May 1980

5 May 1980

5 May 1980

SAS troops storming the Iranian Embassy, 5 May 1980 (© Crown)

Aiding the civil power

The involvement of the SAS in domestic law enforcement was something of a last resort. It only took place after the Home Office had formally requested support for the police from the Ministry of Defence.

During the 1980 siege, the regiment operated under close government supervision via the Cabinet Office Briefing Room A (COBRA), Britain's crisis management command. It also worked in full partnership with the police.

Once the operation was over, the police assumed full authority over the crime scene. Indeed, after the 1980 siege, several SAS soldiers involved were interviewed and questioned by detectives in order to establish that the force used was lawful.

Co-operation

Interviewed in 2015, General Sir Peter de la Billière describes SAS-police co-operation and the political context of the 1980 siege.

Operation Nimrod

Although the terrorists released several sick hostages during the crisis, on Day 6 they killed a captive, believing their demands remained unmet. Following threats that they would shoot more, the British government ordered the SAS to carry out a rescue mission - codenamed Operation Nimrod.

On 5 May, multiple teams of SAS soldiers assaulted the building, one group in full view of the assembled press. In 17 minutes, after a fierce firefight, the siege was over and 19 hostages had been freed. All but one of the terrorists were killed.

The surviving gunman, Fowzi Nejad, was later convicted of conspiracy to murder, false imprisonment and two charges of manslaughter. He was released from prison in 2008 after completing his sentence.

The assault

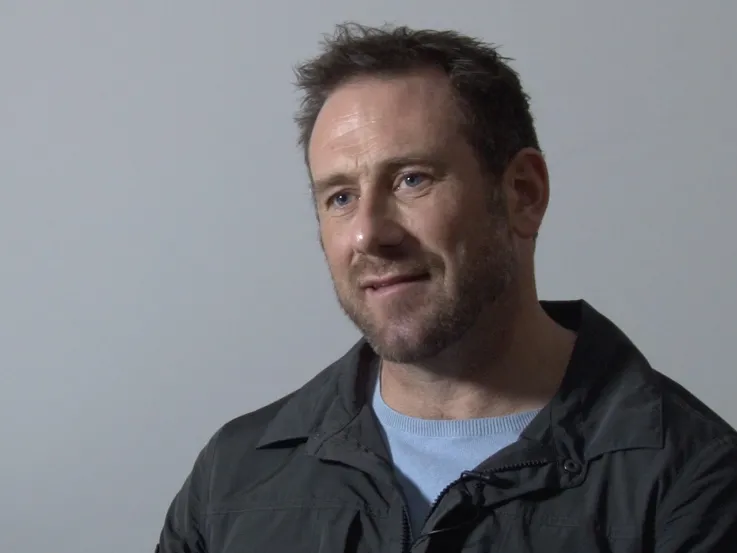

Interviewed in 2017, SAS veteran Corporal Robin Horsfall discusses the planning and undertaking of Operation Nimrod.

7.23pm

7.24pm

7.25pm

7.26pm

7.29pm

7.32pm

7.40pm

Standards of training

Interviewed in 2017, Corporal Robin Horsfall discusses the equipment, training and professionalism required to complete a successful operation.

‘It is highly probable that those involved will receive awards for bravery as a result of Monday’s action. But there will be no citation… to have “beaten the clock” is satisfaction enough for the men of Britain’s most private army.’'The Times' — 7 May 1980

The SAS storm the burning embassy's windows, 5 May 1980 (© Combined Military Services Museum, Maldon, Essex)

Legendary status

The deadly efficiency of the rescue operation, some of which was played out on national television, contributed to the legendary status of the SAS. The images of daring soldiers dressed in black tactical clothing and gas masks became symbols of the prowess of British Special Forces.

The siege also awakened public interest in the Special Forces, its history and operations. This led to an explosion of newspaper articles, books, documentaries and films about the SAS, and other mysterious units, such as the Special Boat Service, that continues to this day.

Public profile

Interviewed in 2017, Corporal Robin Horsfall discusses the public impact of the SAS operation.