Division

At the end of the Second World War (1939-45), American and Soviet concerns over ‘spheres of influence’ led to the partition of Korea. The country was split into the communist Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the American-backed Republic of Korea (South Korea).

In 1949, both the Soviet Union and the United States withdrew their military forces from the Korean peninsula, but the mutual antagonism between the North and South only deepened.

At 4.00am on 25 June 1950, the North Korean Army launched an all-out offensive against the South. The United Nations (UN) Security Council called upon its members to support the Republic of Korea and American forces were quickly sent to the country. They were later joined by troops from many other nations, including Britain.

Map of the Korean peninsula, 1950

Escalation

At first, the North Koreans made rapid progress, quickly taking the South Korean capital of Seoul and driving South Korean and American troops back to the southern port of Busan.

General Douglas MacArthur managed to hold them off after the Waegwan bridge over the Nakdong River was blown up on 3 August. UN forces then began to resupply and fortify their position with a defensive perimeter.

The first British troops landed at Busan soon after. They were immediately sent into battle on the Nakdong, on the western part of the Busan defences. Once reinforced, they and the UN forces counter-attacked.

'Why anybody in the world would want to fight over it [Korea], if it was mine I would have gave it away.'Trooper Jarleth Donellan, Royal Tank Regiment — 1988

American soldiers march north, 1950

15 September 1950

Battle of Incheon

19 October 1950

UN forces take Pyongyang

November 1950

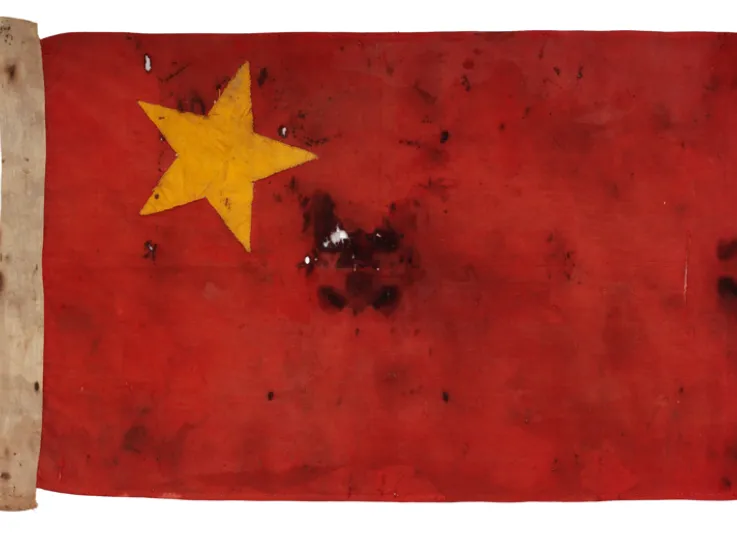

China declares war

Winter 1950

Retreat to the South

Key fact #1

During the retreat, British forces acted as a rearguard until a defensive line was established on the Han River. They had to fight in freezing weather, with heavy snow, icy winds and temperatures as low as -40C.

January 1951

China takes Seoul

March 1951

Counter offensive

Spring 1951

Buffer

Battle of the Imjin River

In April 1951, the Chinese counter-attacked, aiming to break through to the South Korean capital again. They were held up by the UN forces near Kapyong (now Gapyeong) on 22-25 April and on the Imjin River (22-25 April).

The line at Imjin was primarily defended by the British 29th Brigade. The enemy were numerically superior, but the brigade held its position for three days, before being forced to retreat.

The last stand of 1st Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment at Hill 235 on the Imjin helped break the Chinese advance, but resulted in heavy casualties. Only the remains of ‘D’ Company, under the command of Major Mike Harvey, escaped to reach UN lines. The rest of the battalion, including its commander Lieutenant-Colonel James Carne, was captured.

The 1st Battalion was later awarded the United States Presidential Unit Citation for their gallantry.

Imjin River was the bloodiest engagement fought by the British Army since the Second World War, and one of the most decisive defensive battles the Army has ever undertaken.

The actions blunted the Chinese offensive and allowed UN forces to retreat to a stronger defensive position north of Seoul, where they eventually halted the enemy.

'We were holding positions that the Chinese were determined to take, and they didn’t care how many men they lost to get them.'Private Sam Mercer, veteran of the Gloucestershire Regiment — 1988

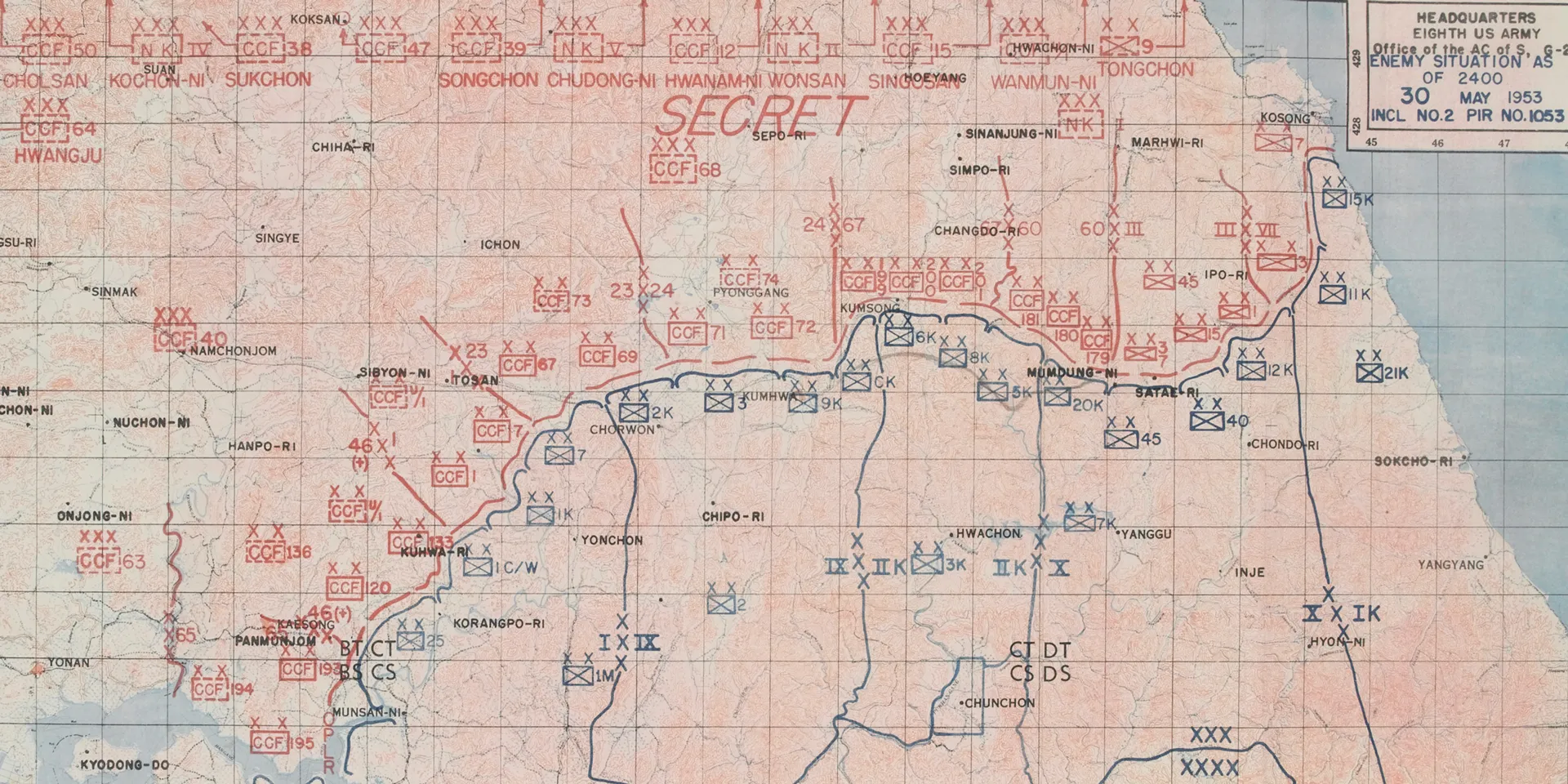

US map of Korea showing UN and enemy dispositions on 30 May 1953

Stalemate

The fighting at the Imjin marked the end of the mobile phase of the war. Stalemate ensued alongside the strategic bombing of North Korea and the implementation of a naval blockade on the country. In June the Soviets indicated they were willing to seek a settlement through arbitration.

Armistice negotiations began at Kaesong in July 1951. But a deal could not be reached, partly due to disagreements over the issue of prisoner-of-war exchanges.

Two years of static fighting followed, often in conditions of extreme cold and heat. Commonwealth troops were deployed on a rotational basis, defending hill positions and carrying out patrols.

Although the war fronts were now static, set-piece operations did occur from time to time, as both sides sought to control key areas of terrain and win a success that might improve their negotiating position.

From July 1951, British forces formed part of the 1st Commonwealth Division under Major-General James Cassels.

The Hook

In October 1951, the 1st Commonwealth Division took part in Operation Commando, a limited offensive designed to disrupt the Chinese potential for attack, dominate the routes across the 38th Parallel and extend diplomatic pressure. The main area of activity was around a ridge overlooking the Imjin River known as ‘the Hook’.

In November 1952, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) repulsed a Chinese attack there. In May 1953, it was again successfully defended, this time by The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding).

The war in numbers

Around 60,000 members of the British armed forces served in Korea; many were National Servicemen.

British forces: Over 1,100 killed and 2,600 wounded.

American forces: Nearly 37,000 killed and 92,000 wounded.

South Korean forces: At least half a million killed or wounded.

Chinese forces: Over 110,000 killed and 380,000 wounded.

North Korean forces: At least half a million killed or wounded.

An estimated two million North and South Korean civilians died.

'The first night I got home I went out with my father to a pub… and a fella said to me, "I've not seen you for a while, where've you been?" I said, "I've been to Korea." And he said, "Oh really, did you have a nice time?"'Fusilier Mike Mogridge, Royal Fusiliers — 1988

Resolution?

On 27 July 1953 an Armistice was finally signed at Panmunjom. But Korea remained a divided nation. In 1954 the 1st Commonwealth Division was reduced to brigade strength before finally being withdrawn in 1957.

North and South Korea have followed very different paths since 1953. South Korea has become an important economic and industrial power in Asia, embracing foreign culture and ideas. It is a successful capitalist country, with huge corporations exporting goods all over the world.

North Korea remains a Communist country. Its economy is focused on supporting one of the world’s largest standing armies. The North Korean nuclear weapons programme has drawn criticism from the United Nations.

Key fact #2

The Korean War has still not officially ended. Skirmishes continue to occur along the 155-mile (248km) border between North and South Korea, which remains the most heavily militarised frontier in the world.

'North Korea is the most dangerous and urgent threat to the peace and security of the Asia-Pacific.'US Vice President Mike Pence — 19 April 2017

Legacy

The Korean War was one of the 'hot wars' of the Cold War era. Between 1950 and 1953, the Korean peninsula was the focus of American-Soviet tensions. After that, the rivalry was played out elsewhere. Ultimately, the conflict had little impact on the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990.

Korea was the first and only test for the United Nations as a military entity. It was also the last time the British Army fought as part of a joint Commonwealth force.

Korea remains a largely forgotten war in British public memory. It is overshadowed by the Second World War and overtaken by subsequent events of the Cold War. But its significance is not lost on those who experienced it and those who continue to live with its legacy today.