Captain David Stirling and Lieutenant Jock Lewes (right) planning a desert operation, 1941 (© Crown)

Early life and education

John Steel Lewes (1913-41) was born in Calcutta (now Kolkata) to an English father and an Australian mother. His father, a wealthy accountant with a puritanical streak, instilled a deep sense of duty and a strong work ethic into his children.

Lewes was raised in Australia, where he enjoyed a rugged outdoor lifestyle, playing a range of sports and excelling particularly at rowing.

As children, John and his brother David took an interest in chemistry. This nearly had disastrous consequences, when John severely injured his hand during one of their bomb-making experiments. But the knowledge they acquired would later pay dividends during his military service.

In 1933, Lewes came to England to study at Oxford University. Here, he continued his sporting endeavours, which earned him the macho nickname ‘Jock’. His prowess at rowing led to his election as President of the Oxford University Boat Club.

A change of heart

While at university, Lewes spent some of his holidays in Germany. For a time, he was impressed by the Nazi regime. Its dynamic and disciplined image appealed to his austere character.

All this changed in November 1938 when the vicious pogrom against the Jews, known as 'Kristallnacht', revealed to Lewes the true nature of the Nazis. He became, instead, their implacable foe.

Keen to develop his interest in international affairs, Lewes’s first job was with the British Council, where he helped to organise its lecture programme. But this proved short-lived. War broke out soon after and he joined The Welsh Guards.

German youth marching under the Nazi banner, c1935

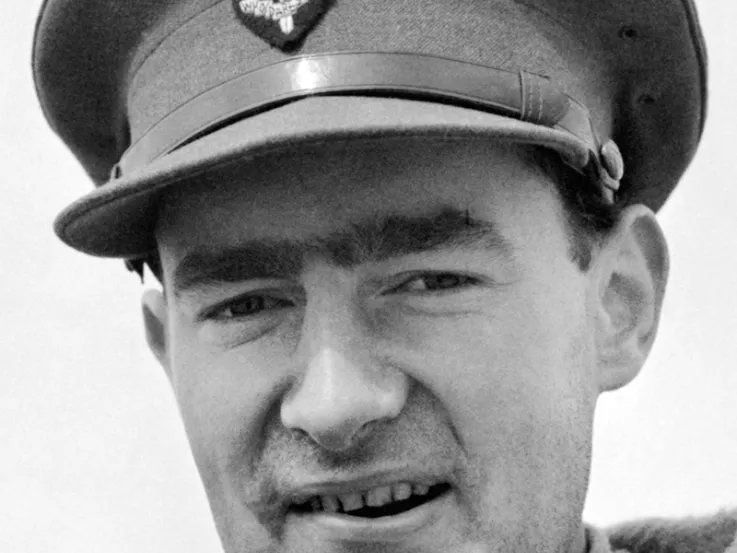

Lieutenant Jock Lewes, by Rex Whistler, 1940 (© John Lewes Archive)

Army life

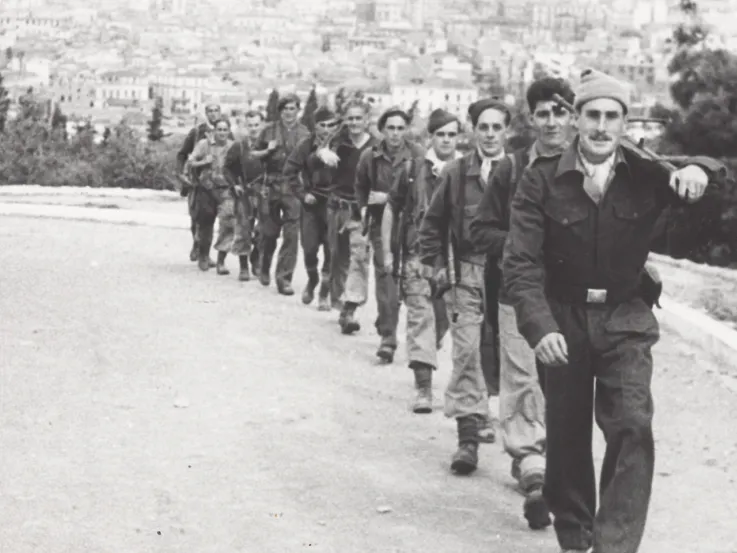

Eager for action, Lewes was quick to join the Commandos, a new unit which specialised in amphibious assault. As part of the Commando group called ‘Layforce’, Lewes was deployed to the Middle East in early 1941.

Like his comrade and SAS co-founder David Stirling, Lewes found his time in the Commandos frustrating. Many operations were cancelled and others ended in failure. Learning from this, Lewes sought to refine the commando concept and develop a more effective way of using these highly trained soldiers.

Impressed by the success of German parachute units - particularly during the Battle of Crete in 1941 - Lewes endeavoured to set up his own small parachute raiding unit. Having obtained some equipment earmarked for India, he arranged with a few comrades, including Stirling, to make the first jump in the Middle East with little instruction or training.

Despite early promise, Lewes encountered further frustration when his plans to use his new unit were repeatedly cancelled. He was instead posted to the besieged port of Tobruk in Libya. Here he experienced intense combat and honed his military skills, especially in small-party raiding and desert endurance.

SAS volunteers undergoing parachute training at Kabrit, c1941 (© IWM (E6390))

SAS recruitment

While at Tobruk, Lewes was repeatedly approached by Stirling who was keen to recruit him into ‘L’ Detachment Special Air Service Brigade. Stirling had established this new unit based on ideas the two men had discussed.

While sceptical about Stirling’s character and commitment, Lewes was eventually won over and became the unit’s training officer. He threw himself into this task, keen to ingrain the skills, discipline and spirit the new unit would need to survive.

SAS recruits board a Bristol Bombay aircraft during parachute training at Kabrit, c1941 (© IWM (E 6404))

Training and leadership

To this end, Lewes established a gruelling programme at their camp in Kabrit, Egypt. In addition to physical exercise and parachute training, it provided instruction in a raft of other skills including desert survival and navigation, first aid, observation and demolitions.

Some of Lewes’s methods were dangerous and experimental. They included practising parachute jumps by leaping from the back of speeding lorries. However, he always led by example.

Following a tragic parachute training accident, in which two men plummeted to their deaths, Lewes and Stirling were the first men to jump the next day, once the faulty equipment had been repaired.

Through this intense training programme and inspired leadership, Lewes imbued the fledgling SAS with the ethos and high standards that are its hallmarks today.

‘Together we have fashioned this unit. David has established it without, and I think I may say I have established it within... the unit cannot die as Layforce died; it is alive and will live gloriously renewing itself by its creative power in the imagination of men.’Lieutenant Jock Lewes in a letter to his mother — 1941

Innovation

Lewes’s other vital contribution to the SAS was the development of a new bomb. Through relentless experimentation he created a weapon which, in defiance of the opinions of ordnance experts, succeeded in combining both high-explosive and incendiary elements. This made the Lewes Bomb ideal for the destruction of aircraft and vehicles.

In November 1941, Lewes took part in the first SAS operation - a parachute drop behind enemy lines in Libya to attack enemy airfields. It ended in disaster. His team was the only one to survive the ordeal unscathed.

The following month, Lewes played his part in the unit’s first great success. While his team’s attacks on airfields were frustrated, they wrought havoc behind the lines, destroying numerous enemy vehicles.

A heavily-armed SAS patrol in their jeeps, 1943 (© IWM (E21337))

An officer and a gentleman

However, Lewes’s service with the unit he had helped establish proved tragically short. On 30 December 1941, returning from a mission at Norfilia airfield, he was killed when his vehicle was strafed by enemy aircraft. This was a tremendous blow to the unit’s morale.

Sergeant Jim Almonds was with Lewes when he died, and wrote in his diary: ‘I thought Jock was one of the bravest men I have ever met, an officer and a gentleman.’

Sadly, Lewes never received the letter recently sent by his girlfriend, Mirren Barford, in which she had accepted his proposal of marriage.