Captured

Staff Sergeant Ernest Trimmer made this splendid model train during his time as a prisoner of war (POW) in Germany. He was serving in Greece during the Allies' ill-fated attempt to aid the Greeks against the Axis invasion when he was captured at Corinth on 26 April 1941.

After this, Ernest was moved to various prison camps before ending up at Stalag 383 in Hohenfels, Bavaria, where he began making the model.

Notification that Sergeant Ernest Trimmer, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, was a prisoner in Germany, June 1941

Trimmer working on a model at Stalag 383, c1943

Conditions

Being a prisoner of war brought many anxieties, hardships and dangers. While western military prisoners of the Germans mostly avoided the terrible treatment meted out to POWs in Eastern Europe, conditions were still far from pleasant.

The camps in which they were imprisoned had only basic sanitation and medical facilities, and the men were often housed in draughty wooden huts.

Guard tower at Stalag 383, Hohenfels, Germany, c1942

Food rations were meagre, of poor quality and lacked variety and nutrition. Luxuries, such as chocolate and cigarettes, were always in short supply and boredom was endemic.

The only highlight in an otherwise drab routine was the occasional arrival of Red Cross parcels. These contained food and treats vital for sustaining both morale and health.

To alleviate the boredom and keep up their spirits, prisoners undertook an amazing range of pursuits, from arts and crafts to music, drama, sports and academic study.

Stalag 383 model club members, c1943

Stalag 383 model club members at work, c1943

Model

When Ernest began working on the model, his only tools were a broken penknife and half a hacksaw blade. He was forced to scavenge cigarette packets, food tins and packaging from Red Cross parcels for materials.

Despite the difficulties, Ernest’s tireless efforts inspired some of his fellow prisoners to form a model club. They worked together to make an entire rail network. Fortunately, the German commandant took an interest in model making and provided the men with a hut in which they could work and lay out their model railway.

Details

The train is marvellously detailed, with hinged doors, a firebox and driver’s cabin, footplate and upholstered carriage seats.

Most remarkably, it was fully electrified. Making the electric motors was particularly difficult and required great skill and ingenuity.

Network

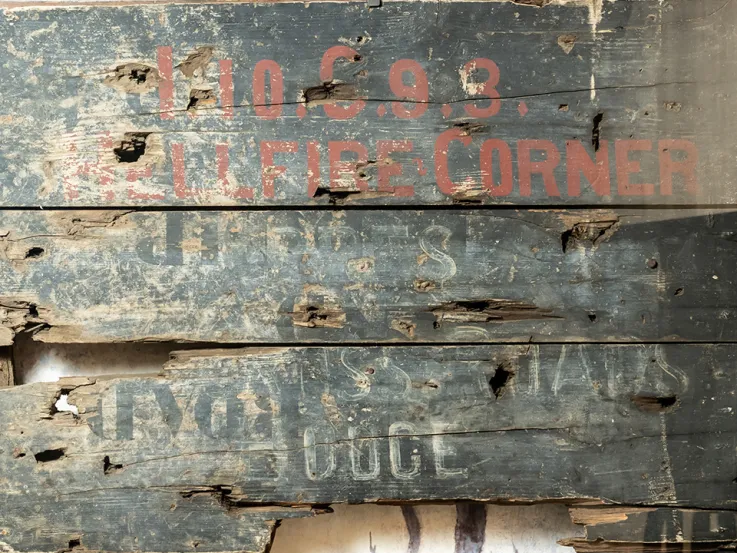

Ernest and his comrades eventually built a network of 73 metres of rail with 22 sets of fully automated points, featuring landscape scenery, advertisements and stations.

Such was the detail and realism that the Germans used the model for demonstration purposes for railway workers. The model was exhibited in a hut at the Stalag, together with many other examples of prisoners’ art and craft works.

Scenery on the model railway at Stalag 383, c1943

A section of the model railway at Stalag 383, c1943

Exhibition

A visiting official from the Red Cross was so impressed with the exhibition at Stalag 383 that he arranged for it to be shipped to London. It was re-displayed in an exhibition held in the grounds of Clarence House in May 1944.

Guidebook for 'The Daily Telegraph' prisoners of war exhibition, Clarence House, 1944

Ernest’s wife came with her family to see the exhibition, expressing: ‘It is hard to describe one’s feelings at the first sight and touch of something he had made, not having seen him for three and half years.’

Ernest was liberated at the end of the war in 1945 and returned home to his wife and family after four years of captivity.