Naval interference

From 1803, Britain was engaged in the last of a series of major conflicts with France. This time, the aim was to curb the imperial ambitions of Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 1807, the British announced plans to stop and inspect merchant ships trading with French-controlled territories and to seize any whose cargoes were thought to be aiding the enemy war effort. This was a response to Napoleon’s Continental System, which prevented European nations from trading with Britain.

The United States (US), which had gained independence from Britain just a few decades earlier, was keen to prevent British naval interference in its trade with France and her allies. It also wanted to stop the British from pressing US citizens into naval service.

Territorial gains

At the same time, some in the US government saw Britain's preoccupation with the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15) as an opportunity to capture its Canadian colonies.

Even if the colonies couldn't be completely occupied, the US at least hoped to seize the Royal Navy's Canadian supply bases and to end British support for anti-American indigenous peoples, especially the confederacy of tribes led by the Shawnee leader, Tecumseh.

Tecumseh, Shawnee Chief (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Indigenous allies

The British viewed the indigenous tribes as useful allies, especially in protecting the approaches to Canada via the Great Lakes region. They supplied them with weapons, which were used in raids against American settlements and the US Army.

For their part, the Americans believed they were entitled to the indigenous territories, since the British had agreed to cede them following the American War of Independence (1775-83).

Outbreak

On 19 June 1812, the United States declared war and invaded Upper Canada (now southern Ontario), which was defended by a small British regular garrison and colonial militia units. Many of these militiamen were from families loyal to Britain, who had been exiled from the US following the War of Independence and were fiercely anti-American.

They responded to the invasion by taking Detroit, located at the western end of Lake Erie, on 15-16 August. Led by Major-General Isaac Brock and his small force of redcoats, the militia defeated a much larger American force.

The British and Canadians held on to Detroit for the next year. The victory also emboldened their indigenous allies to attack American settlements and isolated military outposts.

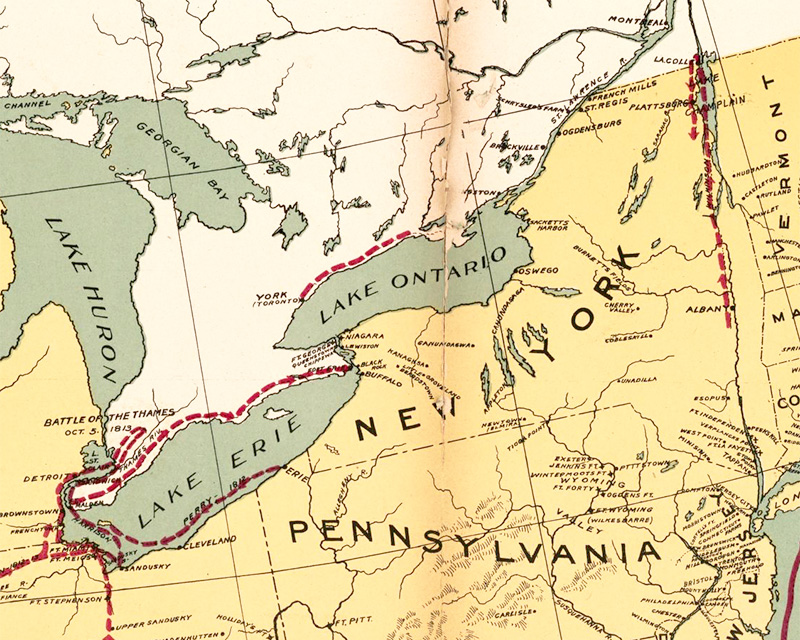

Northern theatre of the War of 1812 (Map courtesy of the Library of Congress)

American attacks

On 13 October 1812, American regulars and the New York militia, commanded by Major-General Stephen Van Rensselaer, tried to establish a foothold at Queenston, on the Canadian side of the Niagara River. They were repelled by British forces, again led by Brock, who was killed in the action.

A simultaneous American thrust north from Lake Champlain into Quebec by General Henry Dearborn was equally unsuccessful, largely because of the uncooperative attitude of the New England militias.

The Americans had hoped the French-speaking people of Quebec would rally to their cause, but this failed to materialise. The Quebec Act (1774) had given its inhabitants formal cultural autonomy within the British Empire, so the majority were unsupportive of the American expedition, which only managed to penetrate about 10 miles across the border.

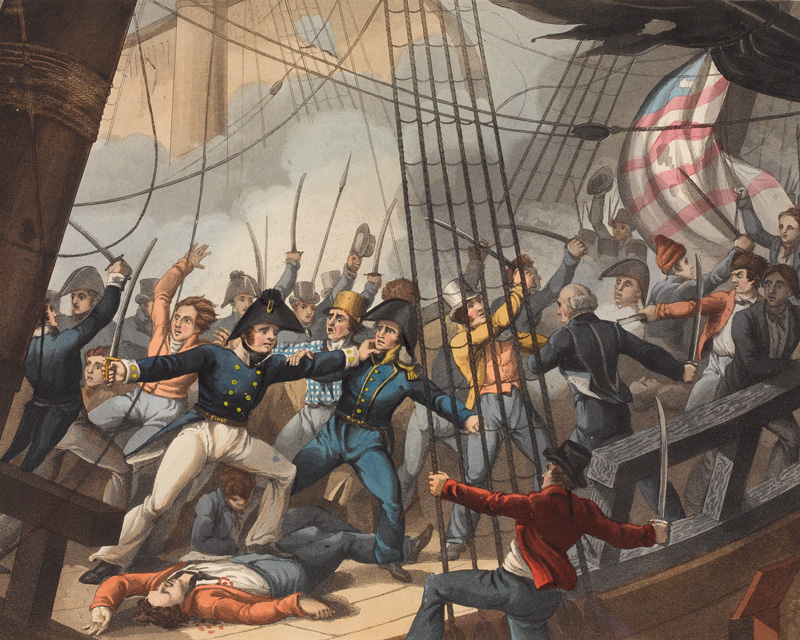

Naval war

The British quickly established a naval blockade along America's Atlantic coastline, but the US won several one-on-one ship duels and captured many merchant vessels.

There were also several actions on the Great Lakes, fought by smaller vessels and gun boats. The American fleet, although greatly outnumbered by the Royal Navy, acquitted itself well in all these engagements.

Renewed invasion

Things improved for the Americans, at least in the west, when they renewed their invasion in 1813. A US naval victory on Lake Erie on 10 September led to the recapture of Detroit (29 September). And the subsequent land victory at the Battle of the Thames (5 October) in Upper Canada restored US ascendancy throughout the region. Tecumseh was killed during the battle, greatly weakening the tribal confederation he had built.

But further east, American forces made little headway in their invasion of Lower Canada (now Quebec and part of Newfoundland). An attempt to take Montreal was defeated at Chateauguay (26 October) by French-Canadian militia and Mohawk warriors under Colonel Charles de Salaberry. The following month, US troops were also defeated at Chrysler’s Farm (11 November).

Along the Niagara front, the Americans managed to secure temporary footholds at York (now Toronto) and Fort George in April-May. But the year ended with the British capture of Fort Niagara (18 December).

Northern impasse

In 1814, US forces were put on the defensive. Napoleon’s defeat in Europe allowed the British to send additional troops to North America and despatch more warships to reinforce their naval blockade, which was successfully weakening the American economy.

Still, the Americans continued their attack on the Niagara front. Bloody fighting there was inconclusive, especially at Lundy’s Lane (25 June) where the two armies fought each other to a stalemate. Next, the British were defeated at Chippewa (5 July), but successfully besieged Fort Erie in August-September. Although the British suffered high casualties attempting to storm the fort, their eventual victory finally ended US ambitions to invade Canada.

Elsewhere, the British took the offensive. However, they encountered the same problems that had earlier plagued the US forces in waging war across vast distances and areas of wilderness. Their advance on Lake Champlain was checked at Plattsburg (11 September). And, on the same day, the Americans won a naval victory on the lake.

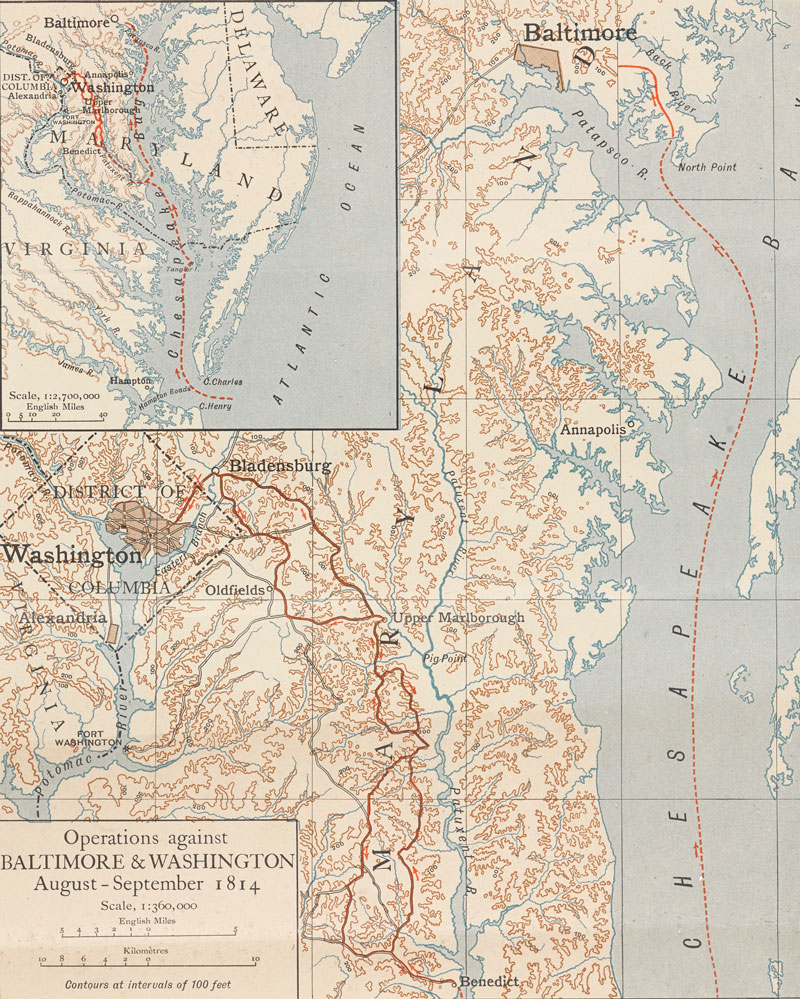

March on Washington

On the eastern seaboard, the British had established themselves on islands in Chesapeake Bay in 1813. The following year, marines and soldiers from these staging posts were landed in Maryland, securing a hard-fought victory at Bladensburg (24 August).

Soon after, Washington DC was occupied and several public buildings were burnt, including the White House and the Capitol. However, the British had to end their assault on neighbouring Baltimore after failing to take Fort McHenry. The British commander, Major-General Robert Ross, was killed in the attempt.

Further north, the British also occupied large stretches of the Maine coastline, destroying foundries and batteries, and sacking several small towns.

New Orleans

The last major actions of the war took place in the south, where the British were keen to take control of access to the Mississippi River and place a further stranglehold on US trade.

At the end of 1814, they launched an attack against New Orleans, hoping a decisive victory there would end the conflict. They were met by the well-organised defences of General Andrew Jackson, who had fortified the canals south of the city.

On 8 January 1815, Jackson's 4,000 men held off an attack by a British force of twice their size. The British eventually withdrew after suffering losses of more than 2,000 men, including their commander General Sir Edward Pakenham.

This unexpected American victory made Jackson a national hero. He would go on to serve as the seventh president of the United States. Ironically, the battle on which Jackson built his reputation had been unnecessary. Diplomats had signed a peace treaty at Ghent on 24 December 1814, but the news failed to reach New Orleans before the fighting commenced.

Treaty of Ghent

While the British naval blockade succeeded in damaging the US, Britain’s own economy was also suffering from the trade disruption.

Prior to the war, Britain had been the US’s largest trading partner, receiving 80 percent of American cotton and 50 percent of all other American exports. Both sides were ready to resolve their differences, especially now that Napoleon had abdicated and the war in Europe appeared to be over.

Although peace terms were agreed in December 1814, the war did not officially end until the Treaty of Ghent was ratified by Congress on 17 February 1815. The US and Britain agreed to return to the state of affairs that had existed before the war, restoring all conquered territory, re-opening trade and ending all naval interference.

Impact

Through the Treaty of Ghent, Britain secured its Canadian possessions for the long term. Their successful defence by British regulars and local militia helped initiate a new sense of Canadian identity, including among the allied indigenous tribes.

After the war, measures were taken to improve Canadian defences, not least the fortifications at Quebec. Its original French Citadel, built of wood, had been maintained by the British following its capture in 1759. During the 1820s, this was replaced with a stronger stone star fort, fitted with larger gun batteries.

British troops would finally leave Canadian territory in 1871, shortly after the colonies had been confederated to form the Dominion of Canada.

For the Americans, the performance of their military during the War of 1812 showed that they were now a growing power to be reckoned with. Indeed, the British would seek out peaceful relations with the US for the remainder of the century.

Most negatively impacted by the conflict were the indigenous tribes. Without British backing, they were unable to withstand ongoing American expansion. Their lands and way of life would be increasingly eroded in the years that followed.