War with France

During the 18th century, Britain and France were imperial rivals in North America. In 1754, their territorial disputes erupted into violence along the frontiers of their respective colonies. Both sides allied themselves with indigenous Americans, giving rise to the American name for the conflict, ‘The French and Indian War’. This regional dispute was soon subsumed into the global conflict known as the Seven Years War (1756-63).

The French initially held the upper hand, winning major victories at Monongahela (1755), Oswego (1756) and Fort William Henry (1757). But after that, a new British government made a concerted effort to reinforce their position in North America, while the French focused more on their European commitments.

Opportunity for attack

In 1758, the British re-captured Oswego and then took Louisburg (in modern-day Nova Scotia). The latter victory opened the sea route to the St Lawrence River and Quebec, the main French settlement in North America.

At the same time, some of France’s indigenous American allies began to make peace with the British. The Royal Navy’s blockade of the coast of France was also restricting supplies to the French colonies. All of this presented the opportunity for a British attack on Quebec.

The armies

By 1759, James Wolfe was a rising star of the British Army, who had fought with great distinction at Dettingen (1743), Culloden (1746) and Louisburg (1758). Although still only 32, Wolfe was appointed to command the 5,000-strong expedition against the fortress of Quebec. Most of his men were regular soldiers, but he also had a small force of colonial militia.

About 13,000 soldiers under Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis de Saint-Veran, defended Quebec and its surroundings. This garrison consisted of French regulars, colonial militia and indigenous Americans. Only around 4,500 of these troops actually took part in the battle.

‘Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals.’King George II on James Wolfe

Stalemate

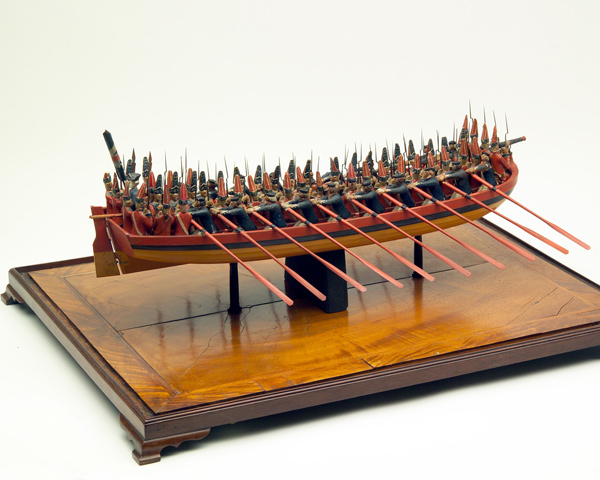

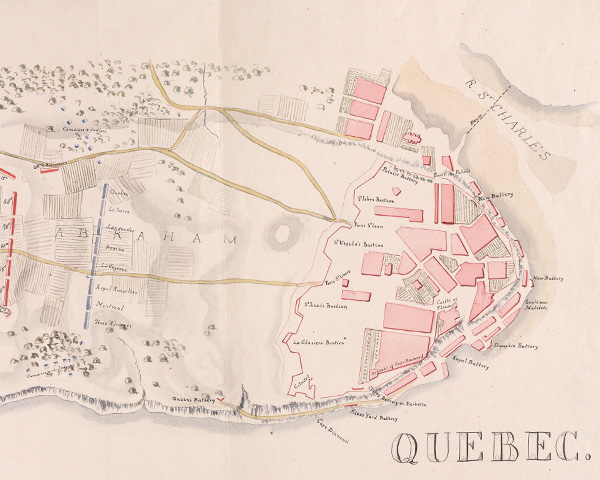

In June 1759, a British amphibious force headed up the St Lawrence River and established a base on the Île d'Orléans, opposite Quebec. This island occupied an almost impregnable position and was defended by a series of redoubts and batteries.

On 31 July, Wolfe attempted to cross the river and land at Beauport, but his men were repelled with heavy losses. In the following weeks, he attacked and destroyed various French settlements along the St Lawrence in an unsuccessful attempt to draw Montcalm out of the city.

By this time, disease was beginning to spread through Wolfe's army and at one point he himself fell ill. He realised that he would have to act quickly before his force was too weak to achieve its objective.

Landing

Reconnaissance of the river had revealed a cove to the west of the fortress that could be accessed by flat-bottomed landing craft. In the early hours of 13 September 1759, Wolfe landed there with his men. At the same time, the British fleet launched a diversionary attack to distract the Quebec garrison.

Climbing a steep path up the cliffs, Wolfe’s troops captured the small detachment guarding this stretch of the riverbank. When they reached the ‘Heights of Abraham’, an undefended plateau behind Quebec, the French came out to meet them.

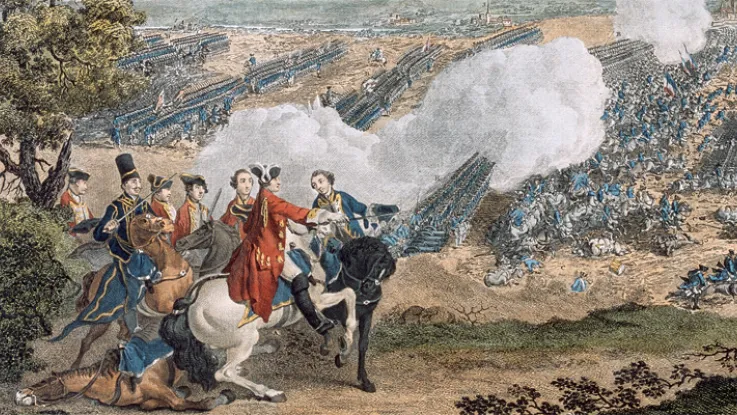

Deployments

Montcalm deployed his troops in a traditional set-piece fashion. This relied on well-drilled and disciplined soldiers who could move in precise order. However, most of his men were not used to acting in concert, and tended to fight and fire as individuals. This greatly reduced the effect of concentrated fire at close range.

Wolfe’s regulars, on the other hand, were used to fighting in rank and firing quick, disciplined volleys. They had been skilfully positioned behind a ridge to protect them from the French batteries situated within Quebec.

Volley fire

Wolfe had also ordered his men to double-load their muskets for the initial volley. In the brief battle that followed, their fire drove the French back into the city. They then repulsed a column of French reinforcements that approached the British rear.

Montcalm and Wolfe were both mortally wounded during the battle. Around 640 French and 650 British were also killed or wounded. The French again retreated inside the city, which finally surrendered on 18 September.

‘I can’t compare it to anything better, than to a family in tears and sorrow which had just lost their father, their friend and their whole dependence.’Lieutenant Henry Browne, who held Wolfe as he lay dying, in a letter to his father — 1759

The consequences

After the capture of Quebec, the French continued to fight. They prevailed in several battles, including at Sainte-Foy (1760), but the British did not relinquish their hold on the fortress.

Meanwhile, Britain's ongoing naval dominance denied the French access to the reinforcements and supplies needed to rescue their deteriorating situation. Following another run of British successes, the war ended in 1763 with France ceding most of its North American possessions east of the Mississippi River to Britain under the terms of the Treaty of Paris.

Ironically, Britain's victory in North America sowed the seeds of a later defeat. The colonists no longer needed British protection against the French threat on their frontier. Their objection to paying for a British garrison was one of the causes of the American War of Independence (1775-83).

However, the people of Quebec did not join the American rebellion. The Quebec Act of 1774 had given them formal cultural autonomy within the British Empire. So, when an American military expedition into Canada was launched in 1775, they did not support it.

The martyr

When news of Wolfe’s death reached Britain on 16 October 1759, it seized the public imagination. He was seen as a young, heroic martyr and a paragon of martial virtue. As the greatest military hero of the mid-18th century, Wolfe was universally celebrated in paintings, prints and sculpture.

His victory at Quebec proved to be the deciding moment in a conflict between Britain and France that shaped the destiny of modern-day Canada.