Early career

Bernard Law Montgomery was born in London in 1887. After attending the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Early in the First World War (1914-18), he was shot through the lung by a sniper during the First Battle of Ypres (1914). His wound was so severe that a grave was prepared for him. However, he went on to make a full recovery.

He saw out the rest of the war as a staff officer, serving in the Battles of the Somme (1916) and Passchendaele (1917). In this capacity, he observed the tactics used by generals like Sir Douglas Haig and became critical of their readiness to accept high casualties during campaigns.

‘The frightful casualties appalled me. The so-called “good fighting generals” of the war appeared to me to be those who had a complete disregard for human life.’Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery — 1958

Dunkirk

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Montgomery was sent to France with the British Expeditionary Force. He commanded the 3rd Division.

Predicting the operation would be a disaster, he trained for tactical retreat. This proved vital during the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940.

North Africa

In 1942, Prime Minister Winston Churchill appointed Montgomery commander of the Eighth Army in the Western Desert. Montgomery rapidly restored the army's flagging morale and ensured his men were properly supplied. For nearly two months, he continued to train and re-equip his soldiers.

‘I want to impose on everyone that the bad times are over, they are finished! Our mandate from the Prime Minister is to destroy the Axis forces in North Africa... It can be done, and it will be done!’Montgomery promising his troops a swift victory — 1942

El Alamein

Montgomery effectively organised the defence of El Alamein against the German forces led by General Erwin Rommel. He countered attacks from both the Italians and the Germans, before delivering the Allies their first major land victory of the war at the Second Battle of El Alamein in October 1942.

This proved to be a turning point in the North African campaign and, indeed, the entire Second World War.

Italy

Montgomery also played a crucial role in the Allied invasions of Sicily and then Salerno in Italy during 1943. This was in spite of disagreements with US Generals Patton and Bradley, who both viewed his previous successes jealously.

Montgomery named his pet spaniel after Rommel. He also had a fox terrier called Hitler.

North West Europe

In June 1944, Montgomery commanded all the ground forces taking part in the Allied invasion of Normandy. Despite setbacks, his skilful planning entrapped and defeated the German forces at the Falaise Pocket.

Later, he convinced US General Dwight Eisenhower to agree to Operation Market Garden, an invasion of the Low Countries and the Ruhr. Montgomery’s plan failed, owing to the large number of German armoured units in the region, and resulted in heavy losses.

However, he redeemed himself with his excellent command during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. By bolstering the American defences with 30 Corps and permitting the deployment of reserves, he helped turn the tide of the battle.

After overseeing the meticulously-planned Rhine crossings of March 1945, Montgomery’s troops advanced into Germany. He eventually accepted the surrender of all German forces in Denmark, northern Germany and the Netherlands on 4 May 1945.

‘General Montgomery is a very able, dynamic type of army commander. I personally think that the only thing he needs is a strong immediate commander. He loves the limelight but in seeking it, it is possible that he does so only because of the effect upon his own soldiers, who are certainly devoted to him. I have great confidence in him as a combat commander. He is intelligent, a good talker, and has a flair for showmanship.’US General Dwight D Eisenhower — 1943

Viscount of Alamein

After the war, Montgomery was made 1st Viscount of Alamein and appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) in Western Germany.

In later life, he was involved in several personal controversies. These included voicing support for apartheid in South Africa, speaking against the legalisation of homosexuality, and criticising US tactics in Vietnam.

His personal memoir, published in 1958, was particularly inflammatory. He was critical of many of his wartime colleagues, including Dwight Eisenhower, who was by then the president of the United States.

‘The United States has broken the second rule of war. That is: don't go fighting with your land army on the mainland in Asia. Rule one is, don't march on Moscow. I developed those two rules myself.’Montgomery on the American war in Vietnam, 'New York Times' — 1968

Unbearable?

Montgomery was arrogant, unlikeable, but ultimately successful. He famously lacked diplomacy and tact when dealing with others. But this directness made him a great military leader.

An example of his difficult personality was when US Major General Bedell Smith made a wager that British forces would not capture the Tunisian city of Sfax by 15 April 1943. Sfax fell on 10 April and Montgomery won the bet. As his prize, he demanded an American bomber to use as his personal transport. Smith, who had only entered into the wager in jest, was ultimately compelled to pander to Monty’s 'crass stupidity' at the bidding of General Eisenhower.

‘In defeat, unbeatable; in victory, unbearable.’Winston Churchill on Bernard Montgomery — 1945

Legacy

Despite his complex character, Montgomery remains one of the best-known generals of the Second World War and one of the British Army’s greatest ever commanders.

An unconventional claim to fame is the lending of his name to the comedy troop ‘Monty Python’, who (sometimes) claim they selected ‘Monty’ in mocking tribute to the legendary Second World War general.

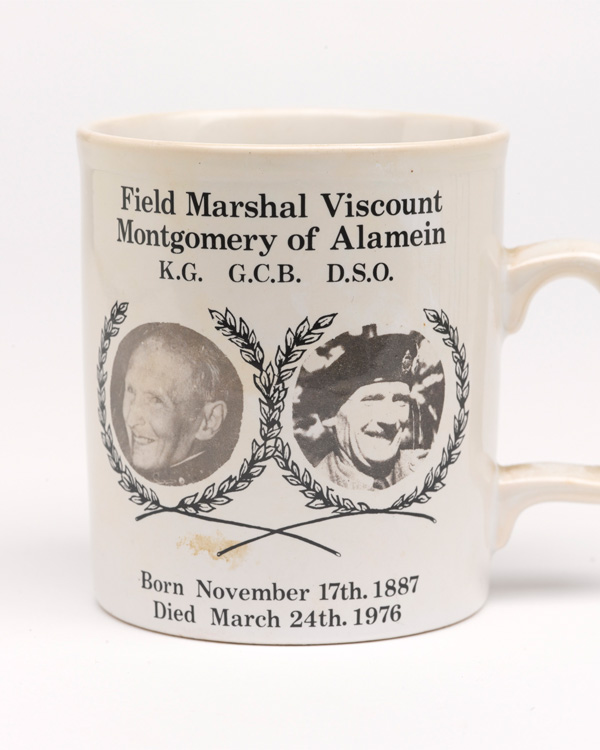

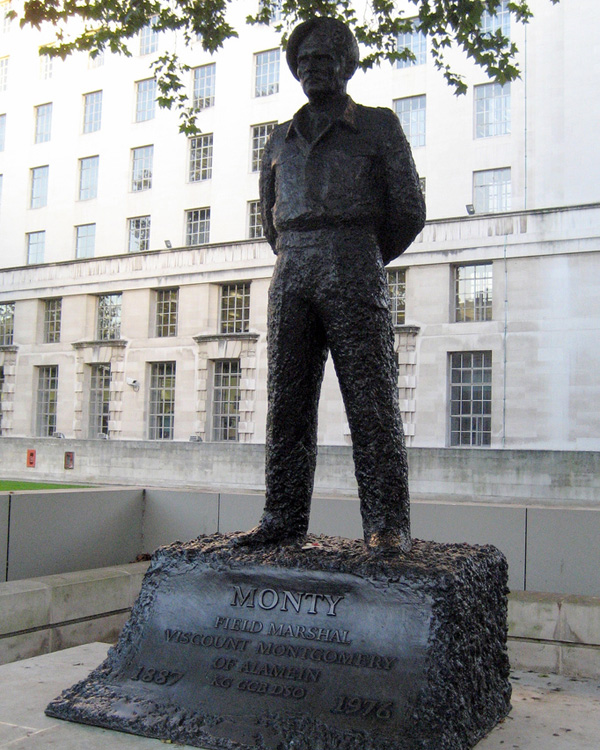

Montgomery died in Isington, Hampshire on 24 March 1976. A commemorative statue stands outside the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall.

Montgomery commemorative mug, 1976

Statue of Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, Whitehall, London, 2006 (Photograph by Wally Gobetz via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

‘The other two would be Alexander the Great and Napoleon.’Montgomery's response when asked to name three generals he admired the most