Formation

After the fall of France in June 1940 the British established a small, but well-trained and highly mobile, raiding and reconnaissance force known as the Commandos. They were party inspired by the mobile commandos of the Boer War (1899-1902).

The first recruits were all volunteers selected from existing regiments in Britain. In 1942, the Royal Navy's Royal Marine battalions were also reorganised as Commandos. They joined the Army Commandos in combined Commando Brigades.

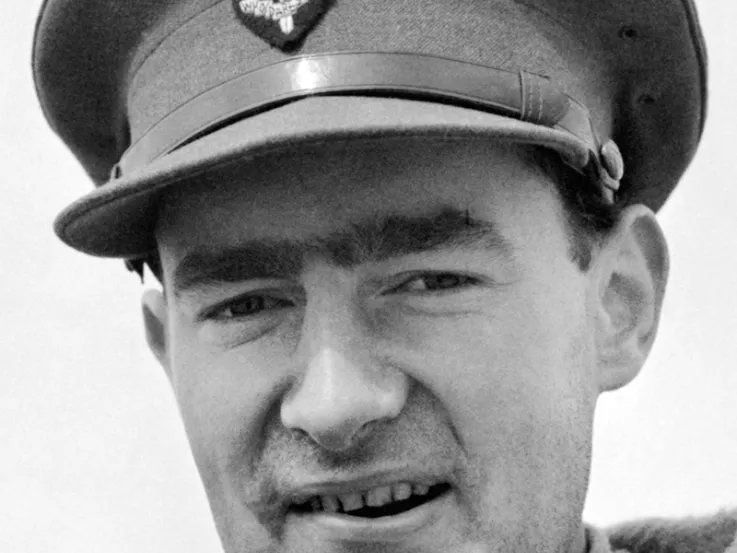

‘I wasn’t prepared for the question: “Why do you want to join the Commandos?” He prompted me with the right answer: “I suppose you want to have a crack at the Boche?”’Lieutenant Colonel George Jellicoe recalling Commando enlistment — 1941

Intensive training

Commando recruits were trained at special centres in Scotland. They learnt physical fitness, survival, orienteering, close-quarter combat, silent killing, signalling, amphibious and cliff assault, vehicle operation, the handling of different weapons and demolition skills. Any man who failed to live up to the toughest requirements would be 'returned to unit' (RTU).

Sergeant Stan Scott

Listen to Stan Scott describing his Second World War experiences as an Army Commando in an interview recorded in 2011.

Early raiding

The first commando raids were made in small numbers, were of short duration and took place at night. Most were against coastal targets in Scandinavia and North West Europe.

Critics argued that descending on the enemy, killing a few guards, blowing up the odd ship, pillbox or fish processing factory, and taking a handful of prisoners was not a cost-effective use of ships, landing craft and highly trained troops. But later the raids grew in complexity and size.

Enemy backlash

Theses early commando raids often instilled fear in the enemy. They so enraged Hitler that he issued his infamous ‘Commando Order’ in 1942, which allowed the summary execution of any captured commando.

This war crime was extended to all British special forces personnel caught in Nazi-controlled territory, although its implementation depended on local circumstances.

Success at St Nazaire

One of the first major missions undertaken by the Commandos was Operation Chariot, a raid on the French port at St Nazaire. The aim was to destroy the only dry dock on the French coast that could be used by the German battleship ‘Tirpitz’. Without a haven for repair, it was unlikely that the new ship would risk sailing in Atlantic waters.

The Allies intended to ram the dry dock gates with an old destroyer, HMS ‘Campbelltown’, whose bows were packed with explosives. Commandos would attack the port facilities as the destroyer rammed the gates.

On 28 March 1942 they succeeded in destroying the Normandie dry dock, preventing its use by Germany for the remainder the war. British casualties were 169 killed in action. Out of 611 men on the raid, fewer than half returned home.

Propaganda

In addition to their operational effectiveness, commando raids also played an important propaganda role. Churchill realised that in the early years of the war, when Britain stood alone, they were one of the few ways of striking back at the enemy.

They also provided a morale boost to the occupied peoples of Europe, reminding them they were not alone.

Expensive lessons at Dieppe

Their next big mission, Operation Jubilee, was a test of the defences of the port of Dieppe on 19 August 1942. Around 5,000 men of the Canadian 2nd Division were joined by 1,075 British commandos, with naval and air support.

The attack was launched at dawn and covered a ten-mile front. The landing force was spotted early so the essential element of surprise was lost. Troops were also landed late or in the wrong place. Air reconnaissance had failed to locate guns hidden in the cliffs surrounding the port. These caused heavy losses.

The raiders got ashore, but received poor support and the German defenders were quick to recover. Insufficient beach reconnaissance meant that many tanks got stuck on the sand’s steep gradient and couldn’t advance.

Within a few hours, more than 3,600 men were killed, wounded or captured. One destroyer and 33 landing craft were lost, with 550 seamen killed.

The Dieppe raid made it clear that seizing a port would be extremely difficult. Any future operations would require adequate air bombardment prior to landing. A need for improved amphibious capabilities was also recognised. The British therefore developed a whole range of specialist vehicles for amphibious operations.

Although some useful information was gained - especially for the planning of the D-Day landings - the operation was a disaster in terms of casualties and equipment lost.

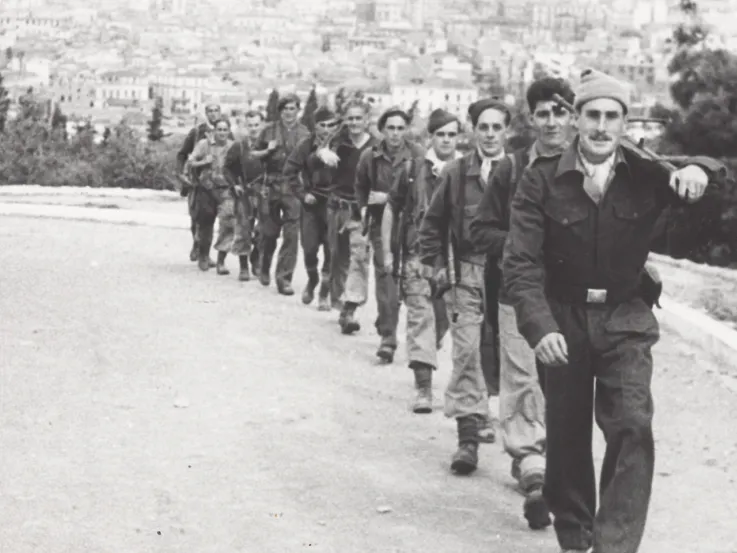

Larger formations

As the Second World War progressed, commandos were deployed in the role of assault troops. They played a key role during the D-Day landings in June 1944, where they destroyed gun batteries and seized bridges and other targets. They performed a similar role in the fighting in Sicily and Italy in 1943-45. And during the operations in Burma in 1943-45, commandos served with the Chindits and in the amphibious landings in the Arakan.

Often used as the spearhead of larger formations, they relied on their training and abilities to overcome difficulties that might have deterred more conventional units.

The evolving role of the commandos saw changes to the training programme at Achnacarry in 1943. It now focused more on the assault infantry role and less on raiding operations. Training now included how to work with larger battlefield formations and how to call for artillery, naval and air force fire support.

Small-scale raiding continues

At the same time, Commandos continued to undertake small-scale missions. In the Balkans in 1943-45 they undertook raids against military installations, often alongside local resistance groups.

They also carried out beach reconnaissance in the build up to D-Day. Operation Tarbrush in May 1944, for example, involved a dozen men from No 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando examining obstacles and mines along the French coast after paddling their dinghies ashore from motor torpedo boats.

Parachute soldiers

Impressed by the performance of Germany’s paratroops in the first two years of the war, Churchill called for the formation of a British equivalent. By late 1941, No 2 Commando had been retrained as parachutists.

One of its first raids took place in February 1942. Parachutists captured the Bruneval radar station in northern France before being evacuated by sea.

The equipment they brought back, along with a captured German radar technician, allowed British scientists to understand enemy advances in radar and to create countermeasures to defeat them. This greatly helped the Royal Air Force in its bombing campaign over Germany.

Expanded airborne roles

The success at Bruneval led to the expansion of British airborne forces. A number of infantry battalions were converted to airborne roles.

This was followed by the creation of the Parachute Regiment in August 1942. The first volunteers underwent training designed to encourage a spirit of self-discipline, self-reliance and aggressiveness. Emphasis was given to physical fitness, field craft and skill at arms.

The highly-trained airborne soldiers went on to serve in North Africa (1942-43), Sicily (1943), Italy (1943-44), southern France (1944) and Greece (1944-45). Five parachute battalions landed in France prior to D-Day (1944) to destroy bridges and gun batteries. They also helped cut off German reinforcements from the Normandy beachheads.

In the summer of 1944 they undertook a daring airborne operation, Operation Market Garden, which aimed to secure the River Rhine crossings and advance into northern Germany.

Disbandment

With Churchill’s defeat in the UK general election of July 1945, the Commandos lost their main supporter.

A subsequent War Office study concluded that large commando forces were no longer required in the post-war world. The Army Commandos were abolished in 1946. However, the Royal Marines Commandos and the Parachute Regiment were retained and continue to this day.

Evaluation

Costly failures, like Dieppe, supported critical views of the Commandos. But many other raids, including the Bruneval and St Nazaire operations, produced excellent results.

However, raids were only part of the story. It could be argued that the Commandos and parachute soldiers gave their most valuable service when fighting as part of - or on the flanks of - the main battle, like in North West Europe and Italy.

Both the Commandos and parachutists won their ferocious reputations by fighting as elite, but traditional soldiers in North Africa, Italy and North West Europe, often in large brigade-sized formations. This was different from the role originally conceived for them in 1940.

Smaller-scale raiding was instead taken up by a host of special forces units. Many of these emerged from the Commandos, but the operations they undertook usually involved working behind enemy lines, rather than fighting as part of the main campaign.