Global areas of operation for National Servicemen, 1947-63

Who was National Service for?

In 1947, it was announced that all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 30 were to be called up. This was quickly changed to all men aged 17 to 21. Initially, conscripts served for 18 months. But in 1950, during the Korean War (1950-53), this increased to two years.

Between the National Service Act coming into force in 1949 and the last National Serviceman being demobbed in 1963, more than 2 million men were conscripted to the British Army, the Royal Navy or the Royal Air Force.

‘At the age of seventeen, I received through the post an official letter inviting me, well, not exactly inviting, but summonsing me to register for National Service.’Private Gordon Kell, Royal Army Medical Corps — 1952-54

Were there any exceptions?

Fully exempt from conscription were the blind and mentally ill, as well as men in overseas government positions.

Officially, no group of healthy men living in mainland Britain was systematically excluded from National Service. But in practice, the Army authorities did not want to recruit large numbers of black and Asian men owing to prevailing racial attitudes at the time.

Despite high levels of immigration in the mid-1950s, no black or Asian men were commissioned and only a few hundred black and Asian soldiers served in the ranks throughout the years of National Service.

Large numbers of those in reserved occupations, ranging from agricultural workers to clergymen, were excused from service on the grounds that their work was vital to Britain’s economic and social life.

Men in Northern Ireland were also excluded from conscription to avoid possible civil unrest among nationalist communities.

Why was National Service necessary?

The end of the Second World War did not bring an end to British military commitments abroad. Britain still needed to maintain her diminishing Empire, occupy post-war Germany and Japan, and re-establish influence in the world, particularly in the Middle East.

The Cold War between the communist Soviet Union and the capitalist United States placed new demands on British manpower. And Indian independence in 1947 meant that Britain no longer had the huge Indian Army at its disposal.

To solve this manpower shortage and meet new post-war challenges, wartime conscription was extended into an obligatory period of National Service for men of military age.

Where did National Servicemen serve?

After training, National Servicemen were often posted to one of Britain's many garrisons around the world. They could end up in places as diverse as the deserts of Egypt and Libya or the jungles of Malaya and Borneo.

For many, this was the first time they had visited a foreign country, let alone lived in one.

‘I was very conscious of the fact that there was no way that I could have ever hoped to visit any foreign country without the assistance of the Queen.’Private Gordon Kell, Royal Army Medical Corps — 1952-54

What did National Servicemen do?

After 1945, Britain was struggling to retain her remaining imperial possessions. Some colonies transitioned to independence relatively peacefully. But in others, such as Kenya and Malaya, National Servicemen found themselves in the front line fighting guerrilla wars.

National Servicemen were also vital in providing the Army with a large garrison force in post-war Germany and a smaller one in Japan. More troops were needed to maintain peace in places experiencing civil unrest, such as Cyprus. Not all National Servicemen fully understood the political factors leading to their deployment.

What was the impact of the Cold War on National Service?

The rise of communism forced Britain to maintain a large standing army in the event of war. Divided Germany became a hotspot for tension and the National Serviceman was the first line of defence. Many of them served with the British Army of the Rhine.

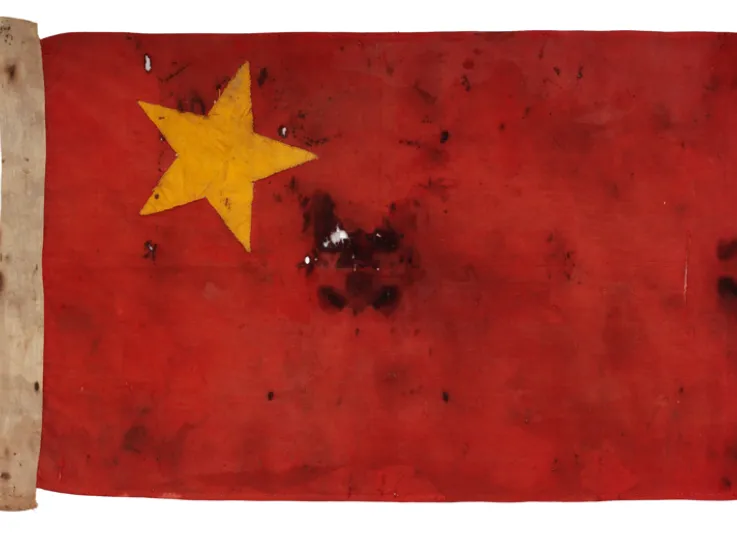

A global war never came to pass. But National Servicemen did see action against communist forces in places such as Korea and Malaya.

How effective was National Service?

The Suez Crisis of 1956 forced Britain to re-assess its use of the armed services. The nation was no longer a world superpower, needing troops to maintain an overseas empire.

The threat of nuclear weapons rendered a large defence force ineffective, as it could only be met with nuclear deterrents. A large army was replaced by a rapid deployment force with modern weapons and equipment. The Defence Review of 1957 initiated a difficult period of transition.

‘So, in general, here’s the youth of the country, dissipating their energies in utterly non-productive wasted activity, while the country, badly needing their labour, moulders and stagnates.’Corporal Ian Colquhoun — 1956-58

Why did National Service end?

The large number of men absorbed into National Service had become a burden to the Army, tying up regular soldiers in training new recruits. National Service also drained workers from the economy, which resulted in opposition from the public, the government, industry and many high-ranking officers.

The last National Serviceman, Second Lieutenant Richard Vaughan of the Royal Army Pay Corps, was discharged to the reserve on 14 June 1963.