Peacekeepers

The British Government ordered the deployment of troops to Northern Ireland in August 1969. This was to counter the growing disorder surrounding civil rights protests and an increase in sectarian violence during the traditional Protestant marching season.

The Roman Catholic population of Northern Ireland had little faith in the local police force, viewing the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) as a pro-Protestant organisation. Initially, it was hoped that the British Army might be more readily accepted as a neutral peacekeeping force.

Members of the Gordon Highlanders on patrol, 1972

Illegal paramilitaries

But this optimism was misplaced. Despite the Army coming under the control of the Secretary of State for Defence in London, many Catholics saw it as a tool of the Unionist Government in Northern Ireland.

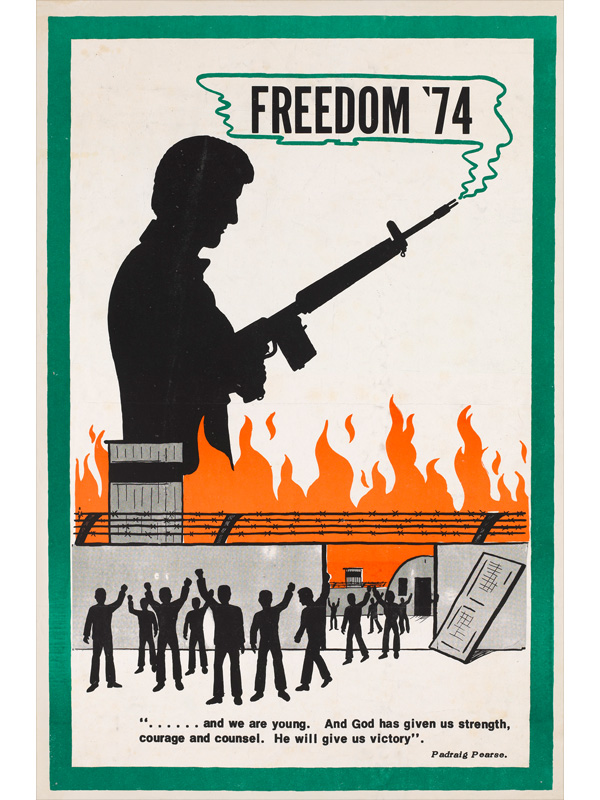

Accordingly, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), which had formed in 1969 and whose membership was growing, increased levels of violence against both the police and the Army.

Loyalist paramilitary groups, including the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), intent on keeping the region part of the United Kingdom, also stepped up their campaign of sectarian violence.

The early 1970s also saw major rioting on both sides of the religious divide.

Irish Republican Army propaganda poster, 1974

On patrol

The Army’s initial troop deployment proved insufficient and reinforcement was soon needed. Early on, the British developed the tactic of operating and patrolling from fortified bases in Northern Ireland's major towns. This set a pattern for the next 30 years.

Map of Northern Ireland

Internment

By June 1971 the situation had deteriorated after the killing of three soldiers and the shooting dead of two men by the Army. In August protest and violence increased further with the introduction of internment: the arrest, interrogation and detention of Republican suspects without trial.

This policy proved counter-productive. It hardened legitimate opposition and bolstered support for the PIRA, particularly in the Catholic housing estates of Belfast and Derry.

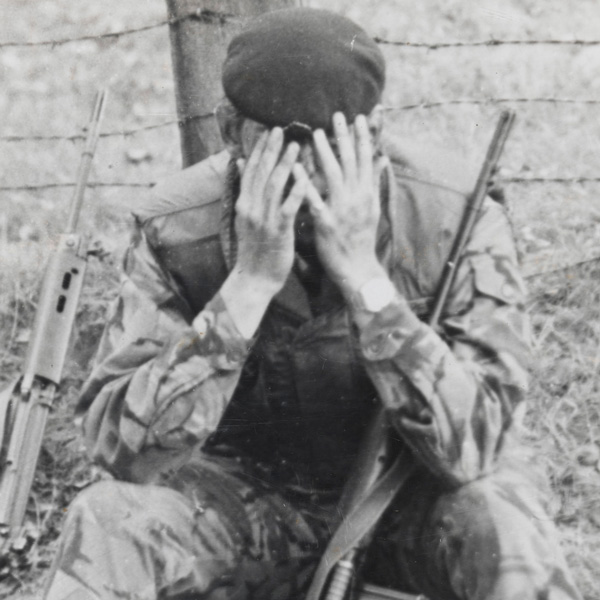

'A little blonde woman came up to me, and she called me all names under the sun, and I had to take it. And, she spat on me. And I cocked my weapon. And I shaked, I literally shook. And the corporal there, tells me, "Tony, leave them. Don’t bother about it. It’s what we’re here for. We gotta’ take what is thrown at us, they’re civilians", and all the thing. And I took it, but I’ll never forget that’.Private Anthony Ali, Northern Ireland — 1970s

Bloody Sunday

On Sunday 30 January 1972, a civil rights march in Derry became the focus of international attention when British troops killed 14 people and wounded another 13. The exact course of events was disputed for years, but in 1998 the British ordered a full-scale judicial inquiry.

In 2010, it concluded that soldiers on duty had ‘lost control’. They had opened fire without warning and before they had come under fire from Republican terrorists.

The incident was a rare case of soldiers breaking the Army's 'Rules of Engagement' which strictly regulated when they could open fire.

‘Bloody Sunday’ swelled the IRA's ranks. Civil unrest continued and violence against the security forces increased. In February 1972 Aldershot barracks was bombed in retaliation. Six civilians and a British Army chaplain were killed.

Urban warfare

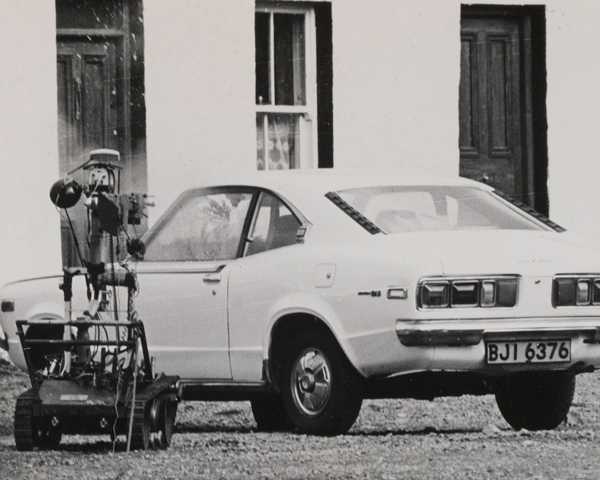

Soldiers and vehicles on patrol in Northern Ireland, undertaking searches and acting as snatch squads, increasingly came under attack from terrorists and rioters using petrol and nail bombs.

Troops honed their urban warfare skills as they countered the threat of snipers, booby traps, mortars and bombs. Riot gear became an integral part of the British soldier's kit.

The introduction of rubber bullets and plastic baton rounds proved controversial. Although classified as non-lethal weapons, their use against rioters resulted in the deaths of several civilians.

Bandit country

In the countryside, particularly South Armagh's 'bandit country', the risk of ambush contributed to the Army's reliance on helicopters both to reconnoitre and ferry troops.

The Army operated a 'tour of duty' policy for troops. The advantage of this was that soldiers had an end in sight and there was a limit to the length of their exposure to stress and danger. The disadvantage was that the build-up of experience and local knowledge could be curtailed and the benefits of continuity lost.

A British Army base in South Armagh, 1977

Direct rule

In July 1972 the Army carried out Operation Motorman. This was an attempt to regain control of ‘no-go areas’, primarily in Derry and Belfast. 1972 also saw the resignation of the Northern Ireland Government and a return to direct rule from Westminster. Further attempts at creating devolved government in the region foundered with the Unionists staunchly resisting the idea of power sharing.

Mainland campaign

By now, the PIRA had a steady supply of arms and money from sympathisers in the Republic of Ireland, the USA and elsewhere. It continued to attack the security forces and economic targets in Ulster, but also increased its activity on mainland Britain.

The bombing campaign of 1974 included attacks on pubs in Birmingham, Guildford and Woolwich in which many civilians died alongside off-duty soldiers. Public revulsion to the bombings led the Government to pass the Prevention of Terrorism Act (1974), which strengthened the police's legal powers to detain suspects. It also made membership of Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groups arrestable offences.

Warrenpoint

In August 1979, the PIRA killed 18 soldiers from the Parachute Regiment and the Queen’s Own Highlanders in an ambush at Warrenpoint near the Irish border. Hours earlier, Lord Louis Mountbatten, a high profile member of the Royal Family, had been killed by a PIRA bomb while on holiday at Mullaghmore in County Sligo.

Politics and violence

In 1981, 10 Republican prisoners starved themselves to death, protesting for political status - the right to be treated as prisoners of war. This greatly increased support for PIRA and its political wing, Sinn Fein.

Throughout the 1980s, as Sinn Fein attempted to gain political influence, the PIRA and other groups such as the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) continued their campaign of violence. In July 1982, 11 soldiers from the Blues and Royals and the Royal Green Jackets were killed in two bomb attacks in London's Hyde Park and Regent's Park.

Attacks

In October 1984, five people died during an attempt to kill the prime minister Margaret Thatcher at the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton.

In 1987, with Anglo-Irish co-operation increasing, Republicans killed 11 people at Enniskillen’s war memorial during a Remembrance Sunday service. The atrocity shocked people on all sides, but it also spurred moderate Irish nationalists to seek a political solution to the conflict.

As the numbers of troops deployed in the Northern Ireland fluctuated, counter-terrorist action by the British Army and intelligence agencies was stepped up. In 1987, eight terrorists were killed in an ambush at Loughall in County Armagh. The following year, the Special Air Service killed members of a PIRA active service unit in Gibraltar.

British forces suffered many casualties in 1988 and 1989. The most severe incident was the killing of 10 Royal Marines in a bomb at the Royal Marines School of Music at Deal in Kent.

'It was always stressful. You'd worry someone would fire into the camp with mortars, you were worried on patrol - some guys were worried about being blown up, other guys were frightened of being sniped. I didn't want to get hit by a nail bomb, because... it was like nuts, bolts, shrapnel, bits of metal. And you didn't want to catch any of that below the waist'.Gunner Graham Matthews on his service in the Province — 1972-74

British soldiers on patrol with RUC officers, 1992

Ceasefires

By the early 1990s, the PIRA had started to concentrate on civilian targets on the mainland. This included the detonation of a large bomb in the City of London in 1993.

Sectarian violence continued. But talks between John Hume, leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), and Gerry Adams of Sinn Fein, along with secret contacts with the British Government, began to form the basis for a new peace initiative.

On 31 August 1994, the PIRA announced a ceasefire. A similar announcement by Loyalist paramilitaries followed in October.

Agreement

In 1996, as talks over decommissioning continued, the PIRA resumed its campaign with a major bomb attack at Canary Wharf in London. The ceasefire was re-established in 1997 and further talks resulted in the 'Good Friday Agreement' in April 1998.

The agreement was announced by all the main parties, except the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), and was backed by referenda north and south of the border.

Decommissioning

The 'Good Friday Agreement' marked a return to devolved government in Northern Ireland with the establishment of a power-sharing administration.

An integral part of the agreement was the cessation of paramilitary violence and the decommissioning of stocks of illegal arms.

British Army numbers and installations in the region were reduced and security procedures gradually relaxed.

A British officer in the aftermath of a terrorist incident, 1977

Troops leave

While the process of normalisation continued, sectarian violence and paramilitary crimes still occurred. The main threat was from paramilitary splinter groups like the Real IRA who carried out the Omagh bombing in August 1998, killing 29 people. This was the worst atrocity of the 'Troubles'.

In August 2005, in response to the PIRA declaration that its campaign was over, it was announced that the British military deployment would end on 31 July 2007.

Security was then transferred to the police. The only troops left in Northern Ireland were there for training purposes.

The cost

The Northern Ireland Victims Commission's 1998 report 'to look at possible ways to recognise the pain and suffering felt by victims of violence arising from the troubles' referred to over 3,600 deaths since 1969, just over half of whom were civilians.

Around 1,400 British military personnel died during the deployment. Of these, half were killed by paramilitaries and half died from other causes. The RUC lost 319 officers to terrorist violence.