Colony of Aden

Situated on the south coast of what is now Yemen, Aden had been a British colony since 1839.

Commanding the southern entrance to the Red Sea, and boasting one of the world's largest natural ports, it became an important British air and naval base on the route to India. It was also crucial for safeguarding access to Middle Eastern oil supplies.

Map of southern Arabia, 1965

Independence

In January 1963, in response to growing nationalist unrest in the region, the British persuaded the sheikhdoms of the Aden Protectorates to merge with the Colony of Aden and form the Federation of South Arabia (FSA).

These surrounding territories had always been semi-independent. But the British were able to influence their external relations and establish local garrisons in return for military protection.

In 1964, continuing to reduce its imperial commitments, the British government announced that independence would be granted to the newly formed FSA by 1968. However, some British forces would stay on in Aden.

Insurgency

Inspired by President Nasser of Egypt, Arab nationalists had formed the National Liberation Front (NLF) in Yemen, which itself had designs on Aden and its surrounding territories.

Their insurgency against British rule began with a grenade attack on the British High Commissioner on 10 December 1963, killing one person and injuring 50.

Radfan

Trouble then developed in the mountainous Radfan region, where dissident local tribesmen raided the road connecting Aden with the town of Dhala near the Yemen border.

In January 1964, three Federation Regular Army (FRA) battalions, with British air support, restored order. But when they withdrew, trouble flared up again, with the rebels receiving NLF support.

On 29 April, the authorities mounted a second expedition, this time with British Army soldiers. Together with two FRA battalions, they advanced rapidly through difficult terrain, capturing the ridges and hills that dominated the tribal areas.

By 26 May 1964, they had taken the main rebel stronghold in the Wadi Dhubsan and suppressed the tribal revolt.

‘My battalion, we had two people killed and a number of injuries. But we had a very successful tour. We found a lot of illegal weapons and... also captured a few terrorists. Once, we had four people in look out positions, including my platoon commander, when he got shot in the arm. And we could kind of tell where the fire was coming from, so we just opened up to see if we could crack whoever was having a go. And that was my first time as a young soldier under enemy fire, and I could feel my knees really trembling. But then... we saw a white flag waving from the building so obviously they were surrendering.’Corporal David Harding, 3rd Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment — 1966-67

Urban guerrillas

From November 1964, the NLF switched its efforts to Aden itself, where it began an urban terrorist campaign. British troops and their families, members of the local security forces and supporters of the government were all attacked.

Although Special Air Service (SAS) operatives were covertly deployed against the terrorists, the NLF’s campaign of intimidation made it difficult for the security forces to gather intelligence, as the local population was unwilling to co-operate.

FLOSY

In 1966, the British government announced that all British forces would be withdrawn immediately on independence. Few locals in Aden believed that the existing FSA government would survive without British support and were therefore wary of being seen to support it.

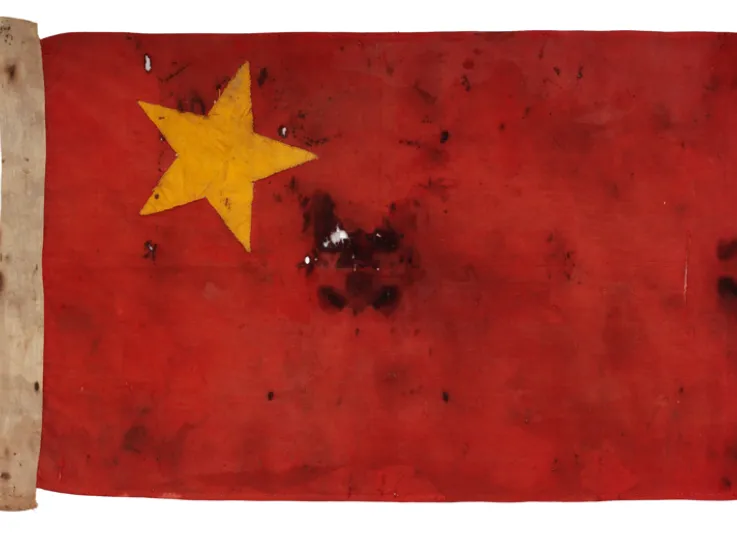

As the NLF escalated their attacks, a second nationalist group - the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY) - also began terrorist activities against the security forces.

Riots

In January 1967, there were riots by the supporters of both groups in the old Arab quarter of Aden. These continued until mid-February, despite the intervention of British troops.

Morale among the local security forces was now at an all-time low. On 20 June 1967, a mutiny in the Federation Army spread to the local police. Eight soldiers of the Royal Corps of Transport were killed when mutineers fired on their lorry.

Crater re-occupied

Although order was quickly restored, rumours that the British were shooting mutineers led to a number of ambushes in the Crater area of Aden. This resulted in the deaths of a dozen more soldiers, including men from The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers and The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

Two weeks later, Lieutenant-Colonel Colin Mitchell led the Argylls back into Crater, which was re-occupied in a blaze of publicity.

‘There was a series of anti-British riots in the town of Crater... And so we started on IS duties, Internal Security, where we formed what was called “The Box”. We had one pair of men with a banner that said “disperse or we will fire”, in Arabic of course. You had a cameraman… to take pictures of local ne’er-do-wells in the crowd. You had your sections of riflemen around and you had one man with a loudhailer, and you had the officer’s clerk that had to record all the events walking along with the officer in the middle of “The Box”, dodging stones. And there were some quite serious riots in Crater and a few shots were fired.’Sergeant John Wells, Aden — 1965-66

Withdrawal

As the November 1967 date for the British withdrawal approached, the NLF and FLOSY began fighting each other for control of Aden, with the NLF gaining the upper hand. In the last week of November, the remaining 3,500 men of the British garrison were evacuated.

End of Empire

Following a short civil war, Aden and the rest of the Federation of South Arabia became part of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. In 1990, this merged with North Yemen to form the Republic of Yemen.

Aden was the British Army’s last colonial counter-insurgency campaign and one of its least successful. The British withdrawal from southern Arabia completed its retreat from Empire, which had started 20 years earlier with the independence of India and Pakistan.