Origins

From 1855, Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) was ruled by Emperor Tewodros II (sometimes referred to as King Theodore), a Coptic Christian. He had established his sovereignty by defeating his rivals in war. But he continued to face many internal rebellions as he tried to enforce his rule.

In 1862, he asked the British government for an alliance and assistance in acquiring the latest weapons and tactical experts to help him, as a Christian ruler, in his wars with his mostly Muslim neighbours. His request went unanswered.

Hostages

The following year, enraged by the Foreign Office’s failure to reply, he seized a number of European hostages. Among them was the British Consul, Captain Charles Cameron, who was kept in chains for over two years.

The hostages’ conditions of captivity varied greatly. The unstable Tewodros tended to treat them alternately with kindness and cruelty according to his mood.

Outcry

Captain Cameron wrote to the British press describing what was happening. This, and the fact that British women and children were numbered amongst the hostages, created a public outcry that forced the government into a response.

Initial diplomatic negotiations and numerous gifts failed to secure their release. By June 1867, in the face of mounting public indignation, the British reluctantly concluded that military intervention was necessary.

‘There has never been in modern times a colonial campaign quite like the British expedition to Ethiopia in 1868. It proceeds from first to last with the decorum and heavy inevitability of a Victorian state banquet, complete with ponderous speeches at the end. And yet it was a fearsome undertaking; for hundreds of years the country had never been invaded, and the savage nature of the terrain alone was enough to promote failure.’Alan Moorehead, war correspondent and author — 1962

The ‘British’ Army responds

As a response was planned, it was made clear that this was not simply a mission of conquest. Once the hostages were freed and Tewodros punished, the military force was to withdraw. There was never any intention of adding Abyssinia to the British Empire.

The force despatched was drawn from the Bengal and Bombay Armies - usually used to maintain British control in India. As such, it comprised British regiments serving in India and locally recruited Indian soldiers.

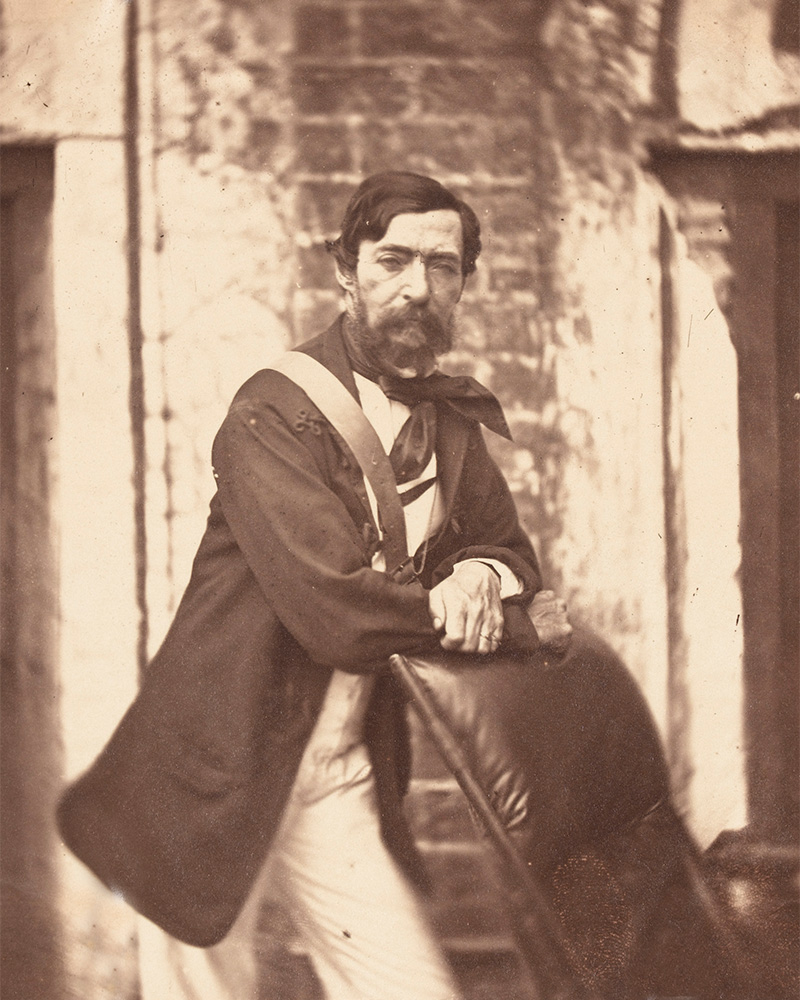

These troops were led by Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier of the Royal Engineers. It was the first time a member of this corps had commanded an expedition.

General Sir Robert Napier, 1858

Expeditionary force

Napier's army was loaded onto ships in Bombay (now Mumbai). Thirteen thousand soldiers were sent along with 40,000 animals, including 44 elephants trained to pull the big artillery guns.

The troops sailed from Bombay on 21 December 1867 and crossed the Arabian Sea, before navigating the Red Sea to the Gulf of Zula, in modern-day Eritrea. They established a base camp, from where they would march inland.

Logistics

Napier’s ability to overcome the logistical challenges that faced his soldiers was essential in the campaign. From the very beginning, supplies had to be moved from India to the landing area at Zula on the coast.

Once they had been consolidated there, the British forces would have to cross 400 miles (640km) of mountainous terrain in inhospitable weather conditions to reach Tewodros’s fortress at Magdala. As an engineer, Napier had a keen appreciation of the difficulties this posed.

Innovation

To reach Magdala, Napier used many technical innovations to keep the army moving and supplied. These included the telegraph and desalination plants to turn sea water into fresh water. A harbour was built with piers and warehouses to help unload and store supplies. Twenty miles (32km) of railway line were laid, complete with locomotives brought from India.

The Royal Engineers built a road into the interior of the country to help the army move more quickly. Speed was a key factor, as the campaign needed to be completed before the torrential June rains made the already challenging terrain utterly impassable.

The advance began on 26 January 1868. It was combined with diplomatic efforts, as the British secured agreements with Tewodros’s enemies to cross their territory without encountering armed opposition. This would also protect lines of communication and supply.

At Magdala’s gates

Napier's diplomacy ensured that the British were able to march freely across northern Abyssinia, but it still took more than two months to reach Magdala. Tewodros’s capital was built on top of a volcanic plug that towered over the local landscape.

But before the British could assault it, they needed to cross the plateau of Arogye. Tewodros’s army, including 30 artillery pieces, was encamped around it in defensive positions, which the British would have to battle through.

Emperor Tewodros’s fortress of Magdala, 1868

Attack

On 10 April, Tewodros ordered his army to attack, rather than hold their positions, in an effort to seize the initiative. They were ill-equipped, and the British and Indian soldiers drove them back into Magdala. The battle lasted just 90 minutes. More than 500 Abyssinians were killed and thousands more wounded. The British suffered a mere handful of injuries.

The following day, the British moved to attack Magdala. Tewodros released all his European hostages over the next two days and murdered the others he was holding. But he still refused to surrender.

On 13 April, the British attacked the fortress. An artillery bombardment covered the advance up the narrow route to the entrance. Once there, the British rushed the outer and inner gates under fire.

Suicide

As the British moved into the fortress, they discovered the body of Tewodros just inside the second gate. Rather than wait to be captured, he had committed suicide with a pistol that had been a gift from Queen Victoria. As news of his death spread, all resistance from the defenders came to an end.

Napier's Anglo-Indian army had won. The campaign had cost just 18 wounded and two killed. No accurate record was taken of how many Abyssinian casualties were sustained.

‘The roll of the drum assembled all the officers and crowds of onlookers around the piled treasures of Magdala, which covered half an acre of ground… Bidders were not scarce. Every officer and civilian desired some souvenir of Magdala.’Journalist and explorer Henry Morgan Stanley recalling the British auction of treasures following the capture of Magdala — 1896

Aftermath

Napier destroyed Tewodros’s artillery and fortress, but not before allowing his troops to pillage Magdala. An enormous auction of loot was then held. It took 15 elephants and nearly 200 mules to carry it back to the coast.

During the long march to the coast, Napier's men faced small attacks from various tribes. For those allies who had granted free passage, however, gifts were made of weaponry.

Napier reached Zula on 2 June, and his troops soon dismantled the base camp, eroding virtually all trace of their presence. On 10 June, Napier sailed for Britain.

The expedition was hailed as a success by a British public that had demanded action. Napier was made Baron Napier of Magdala by Queen Victoria. The soldiers who took part were awarded the Abyssinian War Medal and the battle honour ‘Abyssinia’ was granted to the regiments involved.