A new king

In 1685, King Charles II died. Despite having several children from his many affairs, he had no legitimate children with his wife, Catherine of Braganza. He was therefore succeeded by his brother James, a Roman Catholic.

During his reign, King James II tried to secure religious toleration for his Catholic subjects. He was also keen to strengthen royal central government by reducing the power and independence of the country’s counties and major towns.

He expanded the standing army, seeing it as an essential instrument of royal power. And, following Monmouth’s Rebellion in 1685, he more than doubled its size.

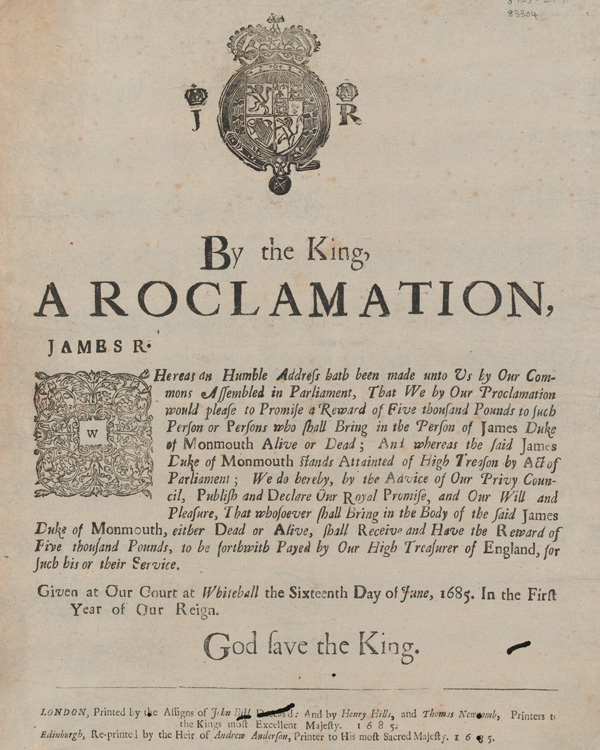

Revolt

James, Duke of Monmouth was the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II, and a Protestant. In June 1685, he landed in Dorset and proclaimed himself king in opposition to his Catholic uncle.

Although popular with the common people in the West Country, Monmouth failed to win support from leading army officers. On 6 July 1685, his raw recruits were beaten by James's army at Sedgemoor. Monmouth was later captured and executed.

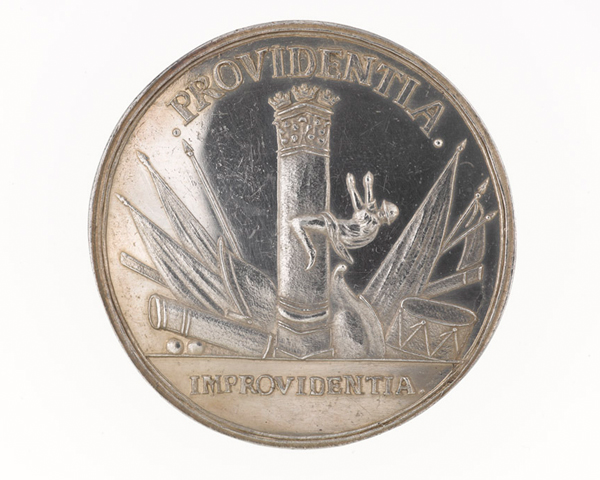

Military professionalism

Following Monmouth's rebellion, James held annual military reviews on Hounslow Heath, an area of open land west of London. He hoped to mould his new regiments into an effective and professional force, and he supervised much of the training himself.

Threat

But holding a military muster so close to London was antagonistic. The king was using the army both to overawe the population and threaten Parliament.

James thought that with the army under his control he would be able to introduce his reforms, unpopular though they were, and move towards a more absolutist style of government, with less Parliamentary oversight.

Control

James was also the king of Ireland and Scotland. He was therefore keen to control the armies of those nations too, even without the full assent of their parliaments, if necessary.

These Irish and Scottish armies remained separate military establishments from James’s English troops. But, as time went on, they were unofficially merged.

Officers

Under Charles II, the officers of the army had largely been the sons of Protestant gentlemen and aristocrats; men who had a stake in the maintenance of the established order.

James still employed many of these Protestant career-soldiers, some of whom had served abroad with the French, in the Anglo-Dutch Brigade, or in England’s garrison at Tangier (in modern-day Morocco).

Loyalty

But James wanted an army that owed its allegiance to him and that would be more willing to enforce his policies. He would have preferred his regiments to be officered wherever possible by Catholics, whom he regarded as the most loyal element in the state.

Many of the old aristocratic and gentry officers were dismissed or resigned their commissions in protest at James’s policies.

Some of the more vociferous anti-Catholic soldiers, like the Earl of Inchiquin, Captain-General of the King’s forces in Africa and Governor of Tangier, had their estates confiscated.

Use of the army

James employed his army extensively in support of his political aims. He introduced Catholic officers where he could, billeted his troops on recalcitrant towns, and also used them to influence elections.

In October 1686, for example, three troops of dragoons were quartered in Gloucester and enrolled as municipal voters so that they could assist in the election of a Catholic mayor.

Army concerns

Unfortunately for James, the purge of thousands of Protestant officers and men being carried out in James's Irish Army by its commander, Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnel, caused alarm to many of the careerist officers he had favoured.

Many of these officers had bought their commissions and, in the eyes of military men, Tyrconnel's actions were an attack on their property rights. James's officers feared that the same thing might happen to the English Army.

Portsmouth captains

Their fears worsened in September 1688, when James ordered the Duke of Berwick to introduce a number of Irish recruits into his regiment, stationed at Portsmouth. John Beaumont, lieutenant colonel of the regiment, and five of his captains refused to receive the new recruits and were subsequently court-martialled and dismissed.

Although James made no further attempts at this - indeed Catholics never made up more than about ten per cent of the army's numbers - the resistance of the Portsmouth captains reflected a widespread fear among English officers that the king planned to introduce Catholic Irishmen into the army.

And in 1688, when the Dutch ruler William of Orange eventually invaded England, these concerns led a key group of officers to conclude that their interests would be better served by joining him.

Prince of Orange

On 10 June 1688, James's wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a son, thereby displacing James's daughter Mary as first in line to the throne. Faced with the prospect of a Catholic succession, leading Protestants made advances to Mary's husband, William of Orange, and offered him the crown of England.

William's main motive in accepting was to secure English troops, ships and resources for his war against King Louis XIV of France. He was also concerned that James might ally England to France.

Landing

On 5 November 1688, William landed at Brixham, near Torbay in Devon, with 14,000 Dutch, French, Brandenburger, Swedish and Finnish soldiers.

A number of James's officers had already secretly agreed to take their troops over to William. But, while some officers did indeed defect, they took few of their soldiers with them.

Confidence

Nevertheless, these desertions were a tremendous blow to James's confidence. And they led him to believe, probably mistakenly, that he could not trust his army.

On 23 November, despite the fact that his men on Salisbury Plain outnumbered William's by two to one, James ordered a withdrawal towards London.

Desertions

That night, Lord John Churchill (later the Duke of Marlborough), James's ablest soldier, went over to William. Further desertions followed, by both officers and men, and James's army rapidly fell apart.

By 10 December, only 4,000 men remained of the original 30,000 ordered to concentrate at Salisbury. James decided to flee the country.

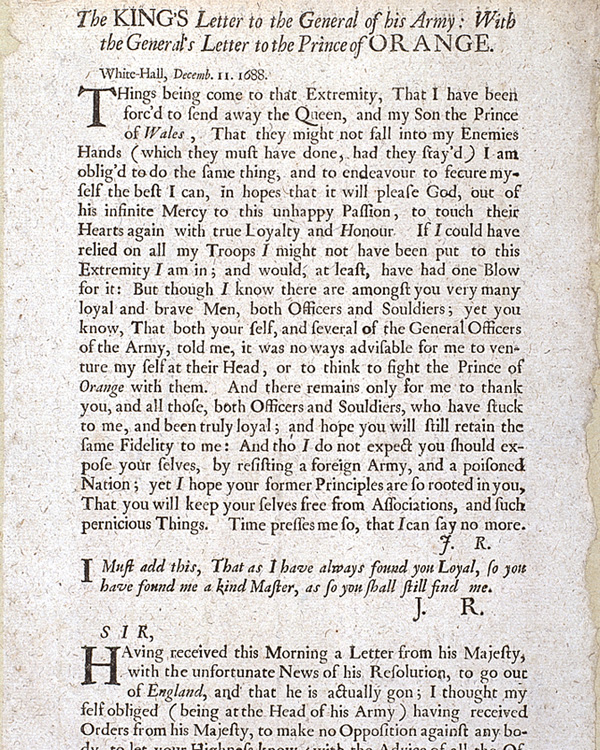

‘Glorious Revolution’

Before he left, James sent a confused letter to his army commander, Lord Feversham, suggesting that he was being forced to flee because he could no longer rely upon the loyalty of his troops.

Feversham interpreted James’s ambiguous remarks about resistance to ‘a foreign army, and a poisoned nation’ to mean that he was absolved from further responsibility. He disbanded the troops under his command, later informing William of Orange that he had done this to ‘hinder the misfortune of effusion of blood’.

On the night of 17 December, a battalion of William’s Dutch Guards took over from the Coldstream Guards at the Palace of Whitehall.

As far as the English Army was concerned, there was nothing 'glorious' about the 1688 revolution. With hardly a shot fired in anger, it had either dispersed, sat out the crisis in its garrisons, or drifted over to William's side.

‘If I could have relied on all my troops I might not have been put to this extremity I am in... But though I know there are amongst you very many loyal and brave men, yet you know that both yourself and several of the General Officers of the Army told me it was no ways advisable for me to venture myself at their head, or to fight the Prince of Orange with them.’King James II’s letter to Lord Feversham — 11 December 1688

Army rebuilt

The army effectively collapsed during William’s takeover. But it was still needed by the new king to help in his wars against the exiled-James II and the French.

It was therefore enlarged, re-trained and re-equipped to fight overseas. Continental soldiers and equipment were also integrated into his force.

Parliament prevails

William's determination to halt French expansionism solved several long-standing political problems in England. These included the debates about royal power and control of the army that had helped bring about both the English Civil War (1642-51) and James II’s overthrow.

The new king agreed to have his power limited by Parliament, and to summon Parliament annually in return for funding for his wars.

In 1689, the Bill of Rights was introduced, which stated that a standing army was illegal without Parliament's consent, and that Parliament had the right to vote funds for its maintenance.

It also passed the Mutiny Act, which effectively gave Parliament a veto over the very existence of an army. To this day, the British Army's continuation depends on Parliamentary consent.

‘The raising or keeping a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace, unless it be with consent of Parliament, is against law.’The Bill of Rights — 1689

Tool of state

This settlement freed the army from domestic political struggles and allowed it to focus on its growing overseas role.

William’s subsequent campaigns during the Nine Years War (1689-97), and then the Duke of Marlborough’s in the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-13), saw the British Army (Scotland and England were united in 1707) assume its place as a key instrument of foreign policy.

Under William and his successors, the army was transformed from an instrument primarily used for domestic repression into a battle-winning asset of grand strategy.

The conflicts of this period earned Britain a place at the top table of great powers, but also established the British Army’s reputation for courage and discipline on the battlefield.