Explore more from British Civil Wars

The Restoration and the birth of the British Army

8 minute read

Protectorate

For much of the 1650s, the British Isles were ruled by Oliver Cromwell in his role as Lord Protector. He sidelined a series of weakened parliaments and governed largely through the New Model Army, a formidable military force which had won the Civil Wars (1642-51) for the Parliamentary cause.

When Oliver died in September 1658, he was succeeded by his son Richard. Having never served in the army, Richard proved unable to control its senior officers. He also struggled to manage the various political factions in his final Protectorate Parliament, summoned in January 1659.

In May of that year, Richard was forced to resign. The army then restored the Rump Parliament (dissolved by Oliver Cromwell in 1653), ending the Protectorate in a bid to revive the Commonwealth.

Political crisis

What followed was a complete breakdown of political order as elements of the army leadership, organised in the Committee of Safety (established in October 1659), competed for authority with the Rump Parliament in a succession of failed regimes.

On 13 October 1659, the army, under the command of Generals John Lambert and Charles Fleetwood, excluded the Rump MPs from Parliament by locking the doors to the Palace of Westminster and stationing armed guards outside.

Growing resentment of military influence in politics, along with exasperation at continued constitutional changes, led to calls either for the Long Parliament (dissolved by the army in 1648) to be reinstated, or fresh elections for an entirely new Parliament.

Monck intervenes

In February 1660, General George Monck marched south from Coldstream in Scotland to lend his support to Parliament. After entering London with his troops, he secured the readmission to the Rump Parliament of those members who had been excluded during Pride's Purge in 1648. The army, under the command of Colonel Thomas Pride, had expelled these MPs to clear the way for the trial of Charles I and the establishment of the Commonwealth.

Convention

The members Monck restored were largely conservative, moderate and sympathetic to the restoration of the monarchy. On 16 March 1660, they dissolved the freshly revived Long Parliament and called for elections for a new assembly that would decide the nation’s future.

This new assembly, known as the Convention to indicate that it had not been summoned by a monarch, consisted of both a House of Commons and a House of Lords (re-established after its abolition in 1649).

Restoration

Assurances given by Charles II in the Declaration of Breda (April 1660) convinced the Convention to invite him on 1 May 1660 to take the throne, resolving that ‘government ought to be by King, Lords and Commons’ together.

Charles promised there would be liberty of conscience, that he would pardon past enemies and not confiscate their wealth (except the regicides responsible for his father's death). Most importantly, he promised to rule in cooperation with Parliament.

‘I stood in the Strand and beheld it, and blessed God. And all this was done without one drop of blood shed and by that very army which rebelled against him.’The diarist John Evelyn witnessing King Charles II’s arrival in London — 29 May 1660

Monck and the army

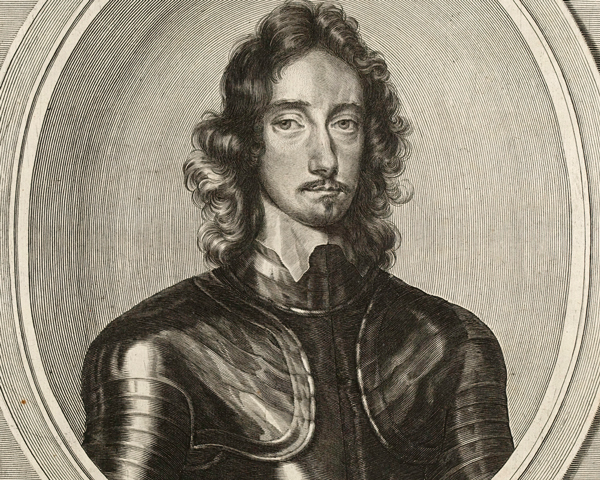

Monck’s role in the restoration had been crucial, but he was something of an enigma. He had fought for King Charles I in Ireland and England before his capture by the Parliamentarians at Nantwich in 1644. He then became one of Cromwell's best generals and his deputy in Scotland.

Though courted by King Charles II in exile, he remained loyal to Cromwell and continued to proclaim his support for his son Richard on his accession as Lord Protector in 1658.

Secret communications

It was only in the face of political chaos that Monck secretly responded to approaches from Royalist leaders. In the months that followed, he applied himself to the delicate task of reconciling the republican New Model Army to growing public sympathy for a restoration of the monarchy.

Charles II’s Declaration of Breda reflected this, being largely based on Monck's secret recommendations. After his restoration, Charles raised Monck to the peerage as Duke of Albemarle and made him Captain General of the King's forces.

Opposition and support

Other Civil War veterans, some of whom had opposed military rule, also played important roles in the restoration. One of the founders of the New Model Amy, Sir Thomas Fairfax, raised troops in Yorkshire to support Monck. By neutralising Parliamentarian forces in the north, he gave Monck the chance to march his soldiers south.

Other senior army officers opposed Monck’s actions. General John Lambert was sent by the Committee of Safety with a large force to intercept Monck and either negotiate with him or force him to come to terms.

Lambert abandoned

But the rank and file of Lambert's army were largely reluctant to fight their old comrades. Many were also angry at not having been paid. His army deserted him, and he returned to London almost alone. In March 1660, Monck had him imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Lambert escaped the following month and tried to rekindle the civil war in favour of the Commonwealth. He issued a proclamation calling on its supporters to rally on the battlefield of Edgehill. However, he was recaptured by Colonel Richard Ingoldsby, a regicide who hoped to win a pardon by handing Lambert over to the new regime.

‘They were as brave troops as the world could show, appearing to be soldiers well disciplined... His majesty did like rather to have them loyal subjects as they now protested, than... as violent enemies'.Account of King Charles II's inspection of New Model Army troops on Blackheath — 29 May 1660

A new army

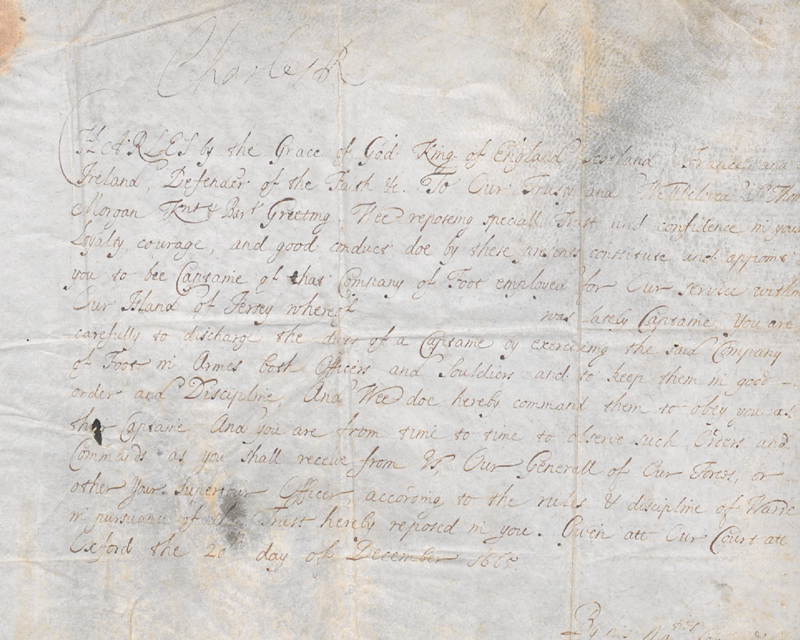

The advantages of a standing army were clear to the new king, not least to the survival of his regime. In 1660-61, Charles raised a force of 5,000 men known as the ‘King’s Guards and Garrisons’. On 26 January 1661, he issued the warrant creating the English Army.

Financed by a new Parliament, it included Royalist units from his exile - like the King's Troop of Horse Guards (later The Life Guards) - and old regiments from the New Model Army which were disbanded and then quickly re-mustered - such as Monck’s Regiment (later The Coldstream Guards).

Indeed, the Declaration of Breda had stated that New Model Army soldiers would be recommissioned into service under the crown, along with the promise that their pay arrears would be remunerated. This incentive had won the acquiescence of many veteran soldiers to the restoration.

Although Charles did not employ every former New Model Army soldier, he found it politically expedient to take many on. Thousands more were paid off through new taxes and coin from the royal coffers.

Ireland and Scotland

Charles was also the king of Ireland and Scotland, so their parliaments paid for units as well. By the mid-1660s, the Irish Army numbered around 5,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry. Its Scottish counterpart had about 3,000 men.

Initially, these remained separate military establishments from Charles’ English troops. But as time went on, they were unofficially merged.

Overseas

Charles’s force gradually increased in size thanks to the demands of foreign wars and the need to garrison new colonies like Tangier and Bombay. These became English possessions in 1661 through the dowry of Charles's new wife, the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza.

Charles redeployed thousands of ex-Parliamentary troops to these two locations, but also to Portugal to assist in its fight against Spain. This helped consolidate royal power by removing potential troublemakers.

Only 800 of the 4,500 veterans sent to Iberia made it home at the end of the war in 1668. Half of these were immediately re-posted to Tangier to fight the Moors.

The first British Army

Charles was the first British monarch to maintain a standing army in peacetime. When he died in 1685, its permanent establishment was as follows:

- England - 3 Troops of Life Guards, 1 Regiment of Horse, 1 Regiment of Dragoons, 2 Regiments of Foot Guards and 5 Regiments of Foot.

- Scotland - 2 Troops of Life Guards, 5 Regiments of Horse, 1 Regiment of Dragoons, 1 Regiment of Foot Guards and 1 Regiment of Foot.

- Ireland - 1 Troop of Life Guards, 3 Regiments of Horse, 1 Regiment of Foot Guards and 6 Regiments of Foot.

Public unease

But not everyone was fully reconciled to the need for a standing army. The New Model Army's political interventions and the Rule of the Major-Generals were still fresh in the memory. People also questioned the cost of maintaining a standing army when the country was not at war.

Some feared that an army under royal command would allow future monarchs to ignore the wishes of Parliament. And their concerns proved well founded when this issue came to a head during the reign of Charles's successor, King James II.