Political situation

On 20 October 1740, Emperor Charles VI of the Holy Roman Empire died, leaving his daughter Maria Theresa as sole heiress of his Habsburg dominions. This was in line with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 in which Charles had attempted to ensure his territories could be inherited by a daughter if he died without a son.

But several major European powers disputed the succession, seeing this as an opportunity to gain territories and influence at Austria’s expense. The struggle that followed is remembered as the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48).

British concerns

King George II was born in Hanover. He was both King of Great Britain and Elector of Hanover – a sovereign prince of the Holy Roman Empire. He therefore had a personal and political interest in upholding Maria Theresa’s succession, fearing any French expansionist moves into the German states of the Empire.

The British also wanted to prevent the French from overrunning the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium). Any enemy presence there directly threatened Britain and its maritime trading links.

In 1742, the government was criticised for voting a subsidy of half a million pounds to Maria Theresa, along with 16,000 troops and five million pounds to support the war. Some accused the King and government of sacrificing British interests to Hanoverian interests.

The 1743 campaign

An experienced veteran, Field Marshal John Dalrymple, 2nd Earl of Stair, was appointed commander of the Pragmatic Army, an allied force of British, Hanoverian and Austrian troops in support of Maria Theresa. The name 'Pragmatic Army' emphasised that it acted only to defend the 1713 Sanction, rather than having any alternative aggressive intentions.

Stair proposed an allied invasion of France from the Low Countries to strike at the heart of the enemy. But King George II dismissed this. Instead, he ordered Stair to march the Pragmatic Army from the Austrian Netherlands towards Germany, in order to threaten the French in Bavaria and to pressurise several German states to side with them.

From February until June, both the French and the Pragmatic Army were moving eastwards, trying to gain a positional advantage, but not committing to battle.

In order to keep his supply route open, Stair tried to secure key posts along the River Main and camped his army between Aschaffenburg and Kleinostheim, waiting for the King to arrive.

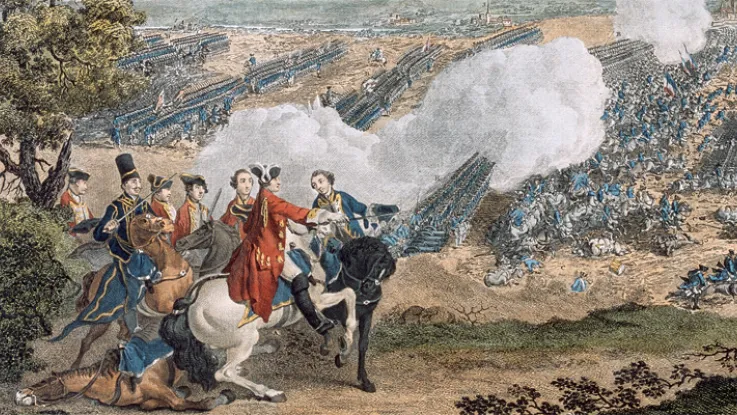

'Exact plan of the Battle of Dettingen', 27 June 1743

Trapped

When King George II arrived on 19 June, he took command, but attributed all the difficulties the army found itself in to Stair and completely ignored his views. Meanwhile, a French force under the Duke of Noailles took the upper part of the Main after Aschaffenburg and cut the supply line of the Pragmatic Army from the east.

He also occupied Seligenstadt, cutting the Army’s supply line from the other side of the Main. George’s army had been outmanoeuvred and was now trapped, facing possible starvation.

On the other side of the river, about 60,000 French troops were camped between Stockstadt and Seligenstadt. At the latter, they built two pontoon bridges to cross to the north and advance towards Dettingen, and then placed artillery along the Main to control the road to Hanau.

'There has been no action yet, nor will be, I believe, till want of provisions and forage force one side to begin or retire, for neither will choose to attempt to pass the river in sight of the other… I have slept three nights upon the ground, rolled up in my cloak without any covering except the sky, and my skin, or rather my hide, is well tanned.’Major Richard Davenport — 22 June 1743

Noailles’ plan

Noailles predicted that the Pragmatic Army would attempt to retreat to Hanau, where they could find supplies and reinforcements. His plan was to block its retreat at Dettingen. At the same time, he would send troops to occupy the village of Aschaffenburg when the allies abandoned it, blocking their escape upstream, trapping the Pragmatic Army from both sides, and then destroying it at his leisure.

The river on the left, and Spessart Hills on the right, would complete the Pragmatic Army's confinement. Noailles’ plan seemed to cover most possibilities.

The battle

Just after midnight on 27 June, King George gave the order for the Pragmatic Army to decamp and begin its retreat. Immediately, Noailles sent infantry to capture Aschaffenburg.

At the same time, his main force, led by the Duke of Gramont, started crossing the Main and moved towards the village of Dettingen. Gramont had precise orders to remain posted to the village and deploy with the boggy ravine at the edge of Dettingen to their front.

But rather than keeping the ravine ahead of his troops, as a natural obstacle to the oncoming enemy, Gramont moved his troops across the bridge over the ravine and deployed them with the swamp behind. In one stroke, this radically changed the tactical situation. The bog, instead of stopping the enemy, turned into a potential sinkhole for the French.

‘All [of Noailles’] measures were disconcerted by one single moment of impatience.’Voltaire, ‘The History of the War of 1741’ — 1756

Positions

By noon, both armies had taken their positions opposite each other, with two lines of infantry in the centre, flanked by cavalry. King George was prevented, with difficulty, from placing himself on the extreme left where it was obvious the severest of the fighting would take place.

The battle started with a charge of the Maison du Roi (French Household Cavalry) and carabiniers on the allied left. The lines of the British cavalry and infantry were pierced, but managed to regroup. The left flank of the allied army was bearing the brunt of the French attacks and was being decimated by French artillery fire from across the Main.

Frightened by the initial crackle of musketry, King George’s horse dashed off, carrying him to the rear to his great embarrassment. The King returned to the right of the line on foot, shouting encouragement to his troops. When the Duke of Ahremberg rode up to him and begged him not to expose himself to the enemy, he declined saying: ’What do you think I am here for - to be a poltroon?’

Infantry fire

Soon after, the French Guards advanced in line against the allied infantry in the centre. But they were met by British platoon fire. This technique involved men drawn up in platoons shooting in strict numbered sequence so it generated a rolling blast of musketry along the entire frontage of a battalion. The French withstood three volleys before they were thrown into disorder and retreated.

Meanwhile, French attacks against the allied right had been easily repulsed by British and Austrian cavalry. The allies then pushed the retreating French through the bog, taking Dettingen.

‘They didn’t even advance one step; their infantry in tight formation stood like a merciless wall.’The Duke of Noailles' letter to King Louis XV — 1743

End of the battle

The whole of the French army was soon retreating in confusion towards the bridges and fords of the Main. One of the pontoon bridges broke, the infantry plunging into the river and drowning in their panic.

The French Guards were particularly criticised for fleeing and throwing themselves into the river in their mad rush to escape. They were mocked by the French public who called them ‘les canards du Main’, ('the ducks of the Main').

The battle ended at around 4.00pm. It was an allied triumph. French casualties were about 4,000-5,000 and allied casualties about half of that.

Despite Stair’s pleading, King George made no attempt to pursue the enemy and capitalise on the victory. Instead, the army retreated to the safety of Hanau.

Impact

In Britain, there was rejoicing. George’s victory initially brought him much popularity. It was extensively celebrated in church halls and public places. Handel was commissioned to compose the ‘Dettingen Te Deum’ for the official commemoration.

But the battle was soon used in Britain to promote political agendas. Critics of King George’s foreign policy emphasised the preference that he seemed to have shown to Hanoverian troops during the battle. The fact that George wore the yellow Hanoverian sash rather than British insignia was taken to be indicative of his priorities and was heavily criticised.

The more sympathetic played up the King’s personal bravery. Indeed, while contemporaries accepted George lacked any flair for strategy and high military command, they maintained he compensated for this through his personal courage and sense of duty.

The battle had demonstrated the fighting qualities of the British Army, but it had little strategic impact on the wider war, the focus of which soon shifted to Flanders. Although the allies had missed an opportunity to pursue and inflict a more decisive defeat on the French, they had had also enjoyed something of a lucky escape themselves thanks to Gramont’s blunder.

‘I think that you committed one mistake, and we two: yours was the passing of the hollow way, and not having patience to wait; ours was first exposing ourselves to destruction, and then not making a proper use of our victory.’Field Marshal The Earl of Stair to Voltaire — 1743