North America

The conflict in North America began in 1754, following prolonged border disputes between British and French colonists. It was known locally as the French and Indian War (1754-63).

Both sides raised their own troops and were supported by military units from their parent nations and by indigenous American allies.

New tactics

Early in the war, the British Army learned some harsh but valuable lessons. In July 1755, a force under Major-General Edward Braddock was advancing to attack Fort Duquesne - established by the French in what grew to become the modern-day city of Pittsburgh, USA - when it was ambushed by French and indigenous American troops in the forests around the Monongahela River.

Aware of the dangers of such an ambush, Braddock had spent time trying to train his men for forest warfare. But when they came under attack, their lack of preparation led to them firing ineffectual volleys into the trees, before eventually breaking and fleeing. Clearly, new tactics were needed.

As a result of this, light companies were added to existing regiments, composed of troops who could scout, skirmish and make good use of natural cover. Eventually, whole regiments of light troops were formed for service in America.

Resources

For the next couple of years, the conflict in North America was marked by skirmishing and raiding, as each side attacked the other’s forts and settlements. The French went on to win further victories at Oswego (1756) and Fort William Henry (1757).

But, while the British gradually increased their military resources in the colonies, the French - concerned about British naval power - were unwilling to risk large convoys to aid the smaller forces they had in North America. Instead, France preferred to focus its efforts on the wider war in Europe.

Louisburg

In 1758, Major-General Jeffrey Amherst captured the French fortress of Louisburg (in modern-day Nova Scotia, Canada). This allowed the British to advance up the St Lawrence River as far as Quebec, where 5,000 French troops under Lieutenant-General Louis, Marquis of Montcalm, occupied an extremely strong position.

Quebec

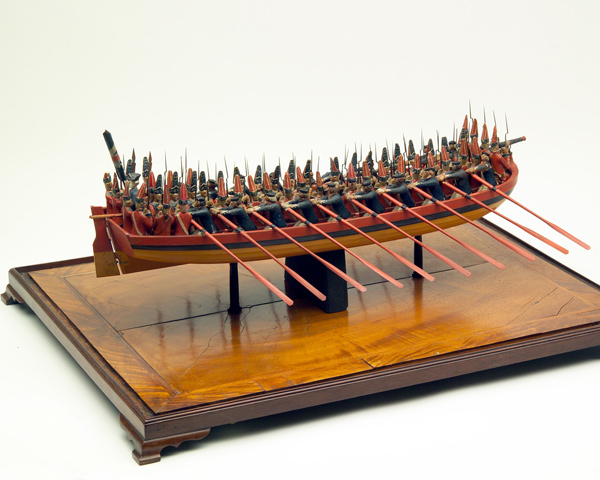

In 1759, a British force under Major-General James Wolfe arrived on board Royal Navy ships with the intention of taking Quebec. Montcalm was cut off, but his position looked impregnable. It seemed he simply had to sit it out until the winter, when the British would be forced to withdraw.

After consultations with his officers, Wolfe decided to land upstream from Quebec. On the night of 12 September, while the Navy created a diversion downstream, Wolfe’s men left their rowing boats and scrambled up a narrow cliff path onto the Heights of Abraham.

The following day, Montcalm left Quebec and attacked Wolfe’s force. The British stopped Montcalm’s men in their tracks with accurate musketry. They then charged, scattering the French.

Both Wolfe and Montcalm were mortally wounded in the battle. Quebec surrendered to the British five days later. A French attempt to recapture the fortress the following spring was defeated.

Montreal

In September 1760, Montreal also surrendered to the British following the Battle of the Thousand Islands. This victory was secured with the help of warriors from the Iroquois Confederacy.

Caribbean

Meanwhile, combined Navy and Army operations in the Caribbean captured several French - and later Spanish - islands. These included Guadeloupe, the richest of the French islands in the Caribbean, which was taken in 1759, and Martinique, seized in 1762.

India

The end of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48) was supposed to have halted Franco-British hostilities in India. However, the fighting there rumbled on. In 1751, for example, the British successfully defended Arcot from the French East India Company and its Indian allies.

The outbreak of the Seven Years War expanded this conflict. The British East India Company now reorganised its armed forces under Lieutenant-Colonel John Stringer Lawrence. And, for the first time, a regular British Army unit - the 39th Regiment of Foot - was sent to the subcontinent.

Lawrence succeeded in conquering the Carnatic region in southern India. But, in 1756, the French and their allies captured Fort William at Calcutta (Kolkata). This was then retaken by Major-General Robert Clive in January the following year.

Plassey

In March 1757, Clive captured Chandernagore, before confronting Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, at Plassey in June.

Clive had only 750 European and 2,500 Indian troops against Siraj’s army of 50,000. But his men were well-disciplined and his dispositions well-planned. Furthermore, Clive was aware that a number of Siraj’s own commanders were plotting against him.

He deployed his men around an orchard and brought up his artillery to drive off an enemy cavalry charge. When Siraj’s infantry advanced, they were stopped by the steady volleys of Clive’s men, who then counter-attacked and drove them from the field.

The British victory at Plassey cleared Bengal of all opposition.

Carnatic

Four years later, following his victory at Wandiwash in January 1760, Lieutenant-Colonel Eyre Coote completed Lawrence’s work in clearing the Carnatic.

The surrender of Pondicherry in January 1761, after a joint army and naval siege that lasted several months, marked the end of French power in India.

Europe

Reacting to the ongoing warfare in North America, France prepared to attack Hanover, which was ruled by the British monarch, King George II. To safeguard George’s continental holdings, the British concluded a treaty in early 1756 whereby Prussia agreed to help protect Hanover. In response, France concluded an alliance with Austria.

The war in Europe began with the French capturing the island of Menorca from the British in June 1756. Two months later, Prussia attacked Saxony, which in turn triggered Austria to declare war against the Prussians. Before long, most major European states had joined the conflict.

Although the British focused most of their efforts at sea and in the colonies, they also joined the struggle on the Continent, giving financial aid to their European allies and sending troops.

Defeat

In July 1757, an army of Hessian, Prussian and Hanoverian troops under the Duke of Cumberland was defeated by the French at Hastenbeck in Hanover. Cumberland was forced to sign the Convention of Kloster Zeven, by which he agreed to disband his force.

However, William Pitt’s government in London rejected these terms. It sent British reinforcements to Cumberland’s army, which was now under the command of the Prussian Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick.

In 1758, a counter-offensive commanded by Ferdinand saw French forces first driven back across the Rhine, and then beaten at Krefeld in June. But in April 1759, Ferdinand was defeated by the French at Bergen.

Minden

Four months later, on 1 August 1759, Ferdinand gained his revenge at Minden, a battle which saw a brigade of British and Hanoverian infantry misinterpret their orders and mount a frontal attack on 60 squadrons of French cavalry. Remarkably, the infantry stood firm when counter-attacked and then returned to the advance.

The victory would have been even more decisive had it not been for the inactivity of the allied cavalry under Lieutenant-General Lord George Sackville, who was later recalled to Britain in disgrace.

Victories

Ferdinand’s British, Hanoverian, Prussian and Brunswick troops won further victories at Emsdorf and Warburg in 1760, Villinghausen in 1761, and Wilhelmsthal in 1762. This enabled him to resist the French attempt to take Hanover.

During these campaigns, he was aided by Lieutenant-General John Manners, Marquess of Granby, who displayed great skill in commanding allied cavalry formations at several battles.

Iberia

In 1762, Spain joined the war and, with French support, attacked Britain’s ally Portugal. After initial setbacks, the Portuguese successfully resisted, thanks to British assistance that included 8,000 troops under Brigadier-General John Burgoyne.

The war dragged on. But most of the European powers were by now militarily and financially exhausted and began putting out peace feelers. Indeed, Russia and Sweden signed separate peace agreements with Prussia in 1762.

Peace

The wider war ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris between Britain, France and Spain, and the Treaty of Hubertusburg between Saxony, Austria and Prussia. The latter agreement succeeded in restoring the situation that had existed in central Europe before the conflict broke out.

Following the Paris deal, Britain kept most of the territories it had captured from the French in North America, as well Spanish Florida, several Caribbean islands, and the African colony of Senegal.

Britain had also secured superiority over the French trading outposts on the Indian subcontinent. This put it in a position to become the greatest economic and military power in India over the years that followed.