Crown v Parliament

Civil war broke out in England in 1642 when King Charles I botched the arrest of his political opponents and declared war against Parliament. In the years that followed, armies loyal to the King fought in pitched battles and sieges against forces raised by Parliament. They fought for control of key cities and strongholds all over Britain.

By 1645 King Charles commanded support in the West Midlands, Wales and the South West. Parliament controlled London, the South East and the North.

Neither side had a clearly defined plan. Parliament needed to defeat the King, but wanted time to recruit and develop their New Model Army. The King could not decide whether to regain the northern counties, or to consolidate his strength in the South West.

On 7 May, King Charles sent his army to the South West, while he moved north. Parliament’s troops converged on his headquarters at Oxford. The King’s army slowly turned and marched south to relieve the city. The New Model Army moved to cut it off.

The Royalist force

The Royalist army was led by King Charles I (1600-49). Its commanders were chosen and promoted for their aristocratic pedigree rather than their experience or ability. Royalist troops were paid, equipped, trained and deployed in much the same way as their Parliamentarian counterparts; but Parliament’s control of the main Channel ports and major armouries like the Tower of London meant the Royalists operated under greater logistical constraint.

At Naseby the army consisted of around 10,000 men. The foot soldiers were armed with muskets or pikes. Charles's 4,000 cavalrymen were led by his nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619-82). Rupert’s drive, determination and experience of European military techniques had brought him several victories prior to Naseby. But his advice against accepting battle there was ignored by his uncle.

Key fact #1

In the week before the battle neither side could be sure exactly where their enemy was! Both forces were only a short distance apart, but covered a lot of ground marching back and forth. The two armies finally met on 14 June just north of Naseby in Northamptonshire.

The New Model Army

Parliament’s New Model Army was unusual for its time. Its commanders were excluded from political power and promoted on the basis of ability, not blood.

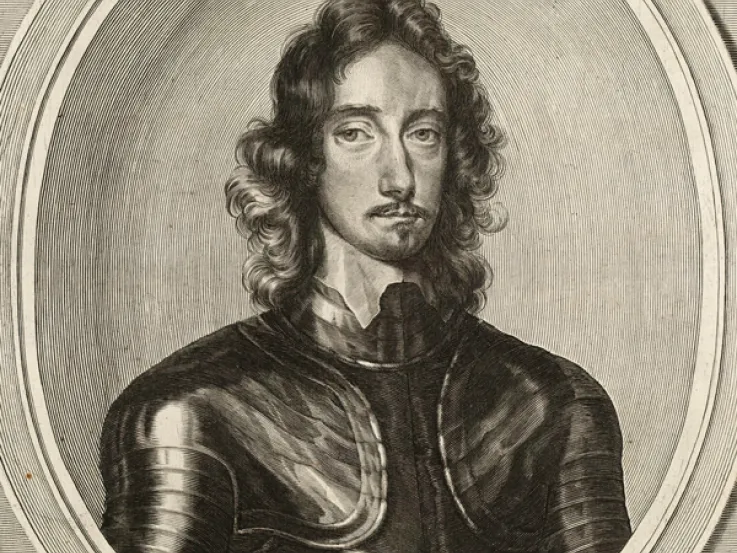

Sir Thomas Fairfax had overall command of the army at Naseby, which consisted of 12,000 men.

Around half were on horseback, under the command of Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell.

Cromwell said of his force: ‘I had rather have a plain, russet-coated Captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a Gentle-man and is nothing else’.

The battle

The armies drew up on opposite sides of a shallow valley, at the base of which ran a stream. Both Royalist and Parliamentarian lines arranged their foot regiments in the centre, and cavalry on the wings. The battlefield was about a mile across and confined on either side by hedges.

Cromwell ordered his dragoons (mounted troops with muskets) to harass the right wing of the Royalist cavalry from the cover of the hedgerow on that side. Unwilling to take fire, and eager to open the battle, Prince Rupert led his cavalry forward. He charged through the New Model Army's left wing and on to the artillery and baggage trains in the rear.

Meanwhile, the foot soldiers from both sides closed and struggled in the centre. Initially, the Royalists appeared to be getting the upper hand. But Cromwell, on Parliament’s right wing, sent the first line of his cavalry to attack and rout the Royalist left wing, and then charge the Royalist foot regiments in the centre. Out-manoeuvred, the Royalists began a fighting retreat north.

Key fact #2

About 1,000 Royalists were killed and as many as 5,000 taken prisoner, along with ‘the whole Booty of the field’ which included the Royalist army’s supplies and guns.

Impact

King Charles and many of his commanders, including Prince Rupert, escaped. But the Royalists were unable to replace the men and resources lost at Naseby. The war continued, but there was little hope. Within a year the King was on the run, and eventually gave himself up.

The King's Cabinet, his office and correspondence, also fell into enemy hands, causing irretrievable political damage. Letters from the Queen demonstrated that she had been trying to enlist support from Catholic powers in Europe. If any of Charles's Protestant subjects had previously been unsure of the King’s attitude to England’s religion and independence, the evidence now seemed clear.

In captivity, Charles managed to strike a deal with the Scots. This reignited civil war, but Parliament and the New Model Army were again victorious. The King himself, in one of the most dramatic and unprecedented events of British history, was tried by Parliament for treason. He was found guilty and executed in 1649.

Key fact #3

The New Model Army secured victory for Parliament. It was radical as a national fighting force not tied to a region or locality. Until 1660, it was the most important force in the country, and dominated English politics, upholding the constitutional experiments of the 1650s. It was also the immediate predecessor of today's British Army.

Legacy

Naseby won the First English Civil War (1642-46) for Parliament and ensured that, whatever happened subsequently, the monarch would never again be supreme in British politics.

Although the monarchy would be restored in 1660, the later Stuart and Hanoverian kings would have a very different, conditional relationship with their parliaments compared to some of their Continental cousins. The possibility of absolute monarchy died with Charles I.