The situation

After failing in 1914-15 to break the muddy stalemate of trench warfare, the Allies developed a new plan. A ‘Big Push’ on the Western Front would coincide with attacks by Russia and Italy elsewhere.

The British wanted to attack in Belgium. But the French demanded an operation at the point in the Allied line where the two armies met. This was along a 25-mile (40km) front on the River Somme in northern France.

On 21 February 1916, aiming to wear down the French in a battle of attrition, the Germans attacked at Verdun. In order to assist their ally, the British launched their attack on the Somme earlier than planned.

Allied commanders

The British Empire forces were commanded by General Sir Douglas Haig. Under pressure to attack at a time and place not of his choosing, Haig also disagreed with his senior commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson. The latter advocated modest ‘bite-and-hold’ tactics, having little confidence about a breakthrough. Haig was more optimistic.

The French were the senior partner in the alliance, so Haig had to accommodate their views. General Ferdinand Foch led the French on the Somme. Originally, their role in the operation was much greater. But the desperate situation at Verdun reduced this.

Battle plans

Haig’s plan was for the British Fourth Army to break through in the centre, while the Third Army in the north and the French Sixth Army to the south made diversionary attacks. If successful, the Reserve Army, including cavalry, would then exploit this gap and roll up the German line.

The Germans were stationed behind a formidable set of defences, the strength of which had been underestimated by Allied intelligence.

Key fact #1

The bulk of British troops involved in the Battle of the Somme were inexperienced volunteers of the 'New Armies'. They had been recruited in 1914-15.

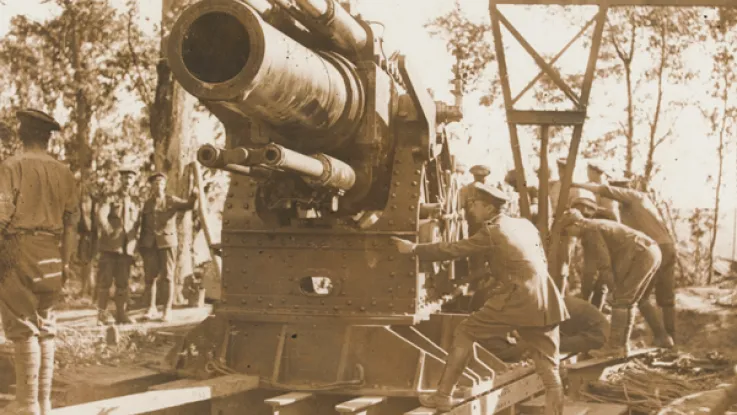

Prelude

On 24 June 1916, the British began a seven-day preliminary bombardment. Haig’s artillery was expected to destroy German defences and guns, and cut the barbed wire in front of the enemy lines. When the attack began, it would provide a creeping barrage behind which the infantry could advance.

The British believed that the Germans would be so shattered by this bombardment that the infantry would rush over and occupy their trenches. But they overestimated their firepower. The guns were too thinly spread for the task in hand.

The British fired 1.5 million shells. Many were shrapnel, which threw out steel balls when they exploded. These were devastating against troops in the open, but largely ineffective against concrete dugouts. At the same time, a lot of shells were defective. The German defences were not destroyed and in many places the wire remained uncut.

The Allies also used mines to destroy the German lines before the battle. One was detonated at Hawthorne Ridge 10 minutes before Zero-Hour, unwittingly signalling to the Germans that an attack was coming.

Key fact #2

Estimates suggest that as many as 30 per cent of the shells fired in the bombardment before the Battle of the Somme failed to explode.

The first day

At 7.30am on 1 July 1916, 14 British divisions attacked. In most cases they were unable to keep up with the barrage that was supposed to take them through to the German trenches.

This gave the Germans time to scramble out of their dugouts, man their trenches and open fire. Haig’s infantry were met by a storm of machine-gun, rifle and artillery fire. They suffered over 57,000 casualties during the day.

Although the French made good progress in the south and there were some local successes, in most places the attack was a bloody failure. But with the French still under pressure at Verdun, there was no question of calling off the offensive.

‘Went over top… after an interminable period of terrible apprehension. Our artillery seemed to increase in intensity and the German guns opened up on No Man’s Land. The din was deafening, the fumes choking and visibility limited owing to the dust and clouds caused by exploding shells. It was a veritable inferno. I was momentarily expecting to be blown to pieces. My platoon continued to advance in good order without many casualties and had reached half way to the Boche line. Suddenly... an appalling rifle and machine gun fire opened against us and my men commenced to fall. I shouted “down” but most of those that were still not hit had already taken cover. I dropped in a shell hole and occasionally attempted to move to my right and left but bullets were forming an impenetrable barrage and exposure of the head meant certain death. None of our men was visible but in all directions came pitiful groans and cries of pain.’Lieutenant Alfred Bundy — 1 July 1916

From July to November

More attacks between 3 and 13 July resulted in a further 25,000 casualties. But, gradually, the British tactics improved.

On 14 July, four British divisions made a dawn attack on Longueval Ridge. Supported by an intense artillery bombardment, they caught the Germans by surprise and by mid-morning they had captured the ridge.

Attacks continued through the summer, mostly on a series of individual objectives, with the Germans frequently mounting counter-attacks of their own. The Some offensive ultimately included 12 separate battles, many of which became slogging matches that lasted for weeks.

On 18 November 1916, with the weather deteriorating, Haig shut down the offensive. The Allies had only advanced seven miles (12 km) and there was still no breakthrough in sight.

In the process, the British Empire had suffered 420,000 casualties and the French 200,000. German losses were at least 450,000 killed and wounded.

Key fact #3

On 15 September, the British used tanks for the first time in support of an attack on Flers-Courcelette. They advanced about 1.5 miles (2.4km), but failed to make a breakthrough.

Success or failure?

For many, the battle exemplified the ‘futile’ slaughter and military incompetence of the First World War. Yet Haig had no option but to fight on the Somme. And despite his controversial tactics, the battle provided a tough lesson in how to fight a large-scale war.

A more professional and effective army emerged from the battle. And the tactics developed there, including the use of tanks and creeping barrages, laid some of the foundations of the Allies’ successes in 1918.

The Somme also succeeded in relieving the pressure on the French at Verdun. Abandoning them would have greatly tested the unity of the Entente.

‘The tragedy of the Somme battle was that the best soldiers, the stoutest-hearted men were lost; their numbers were replaceable, their spiritual worth never could be.’Unidentified German soldier

German losses

One German officer described the Battle of the Somme as ‘the muddy grave of the German Field Army’. That army never fully recovered from the loss of so many experienced junior and non-commissioned officers.

In the spring of 1917, the Germans retreated to the ‘Hindenburg Line’, a shortened defensive position. This move was a direct consequence of troop shortages resulting from the Somme fighting.

Key fact #4

The huge losses among the 'Pal’s Battalions' on the Somme plunged many British communities into grief. The battle, especially its first day, has become a popular symbol for the 'futility' of war.

On a battlefield far, far away...

For many at home, their first glimpse of trench warfare came from Geoffrey Malins's film 'The Battle of the Somme' (1916).

Filmed at the start of the battle, it mainly shows real events, although some scenes were staged for the camera. The film defined the popular image of the war, and indeed created the genre of war cinema.

It was also hugely popular with audiences, who hoped to glimpse their loved ones and were shocked to view its graphic depictions of war. During its first six weeks, the film was seen by nearly 20 million people in the UK, almost half the population. This record was only surpassed in 1977 by 'Star Wars'.

Thiepval Memorial and Anglo-French Cemetery

Commemorations

Over 150,000 British soldiers are buried on the Somme. The cemeteries there were created by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) and have become sites of pilgrimage and tourism.

The Royal British Legion and the CWGC remember the battle on 1 July each year at Thiepval Memorial. This commemorates 72,000 officers and men who have no known grave.