The problem

By the end of 1914, after a brief mobile period, the Western Front had become a complex system of trench defences, with Allied and German troops facing each other from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border.

The result of this was stalemate and deadlock. Some way had to be found to break through the enemy defences, to ‘the green fields beyond’.

The Germans tried using poison gas to achieve this in April 1915. Despite some early success, countermeasures were developed and the Allies too began to use the weapon against its inventors.

A secret solution

The British began to ponder a mechanical solution to trench warfare. Lieutenant Colonel Ernest Swinton, Royal Engineers, suggested an armoured vehicle, but initially received little interest from the War Office. Instead, it was the Admiralty that first embraced the idea of ‘Land Ships’.

The War Office was eventually persuaded too. In January 1915, trials were undertaken at Shoeburyness in Essex. Despite some early failures, by August 1915 the Landships Committee had decided to continue the project.

Royal Navy assistance

In tandem with Fosters of Lincoln, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) - who were already experimenting with armoured cars - tasked their engineers to design a prototype tracked vehicle. This was based on wheeled tractors with American-made tracks.

The resulting machine was named ‘Little Willie’ after Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany. But it was not a total success, and was unable to meet some of the military's requirements.

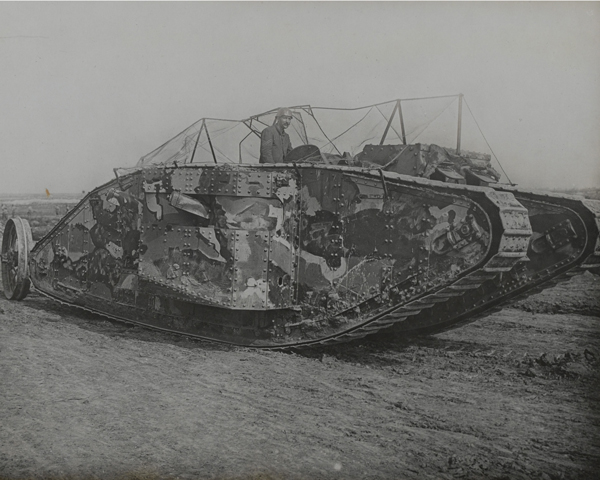

Centipede

Other designs were also developed, including one named His Majesty's Landship ‘Centipede’. This used specially designed tracks and other features, including the familiar rhomboid shape. It met War Office requirements, and following construction in January 1916, the new machine was secretly tested at Lincoln on the night of 19-20 January.

Known as ‘Mother’, it faced intensive trials over the coming months. The results were encouraging and on 12 February 1916, 100 were ordered by the Minister for Munitions, David Lloyd George.

Men and machines

The men who would operate the new secret weapon were recruited from across the army. They formed the Motor Machine Gun Service, part of the Machine Gun Corps. Later, on 1 May 1916, the tanks were renamed the Heavy Section, Machine Gun Corps.

During the spring of 1916, the new force trained at Bisley and later Elveden in Suffolk, under the command of Swinton. By then, tanks had evolved into two broad types. The ‘male’ was armed with two six-pounder guns and machine-guns, while the ‘female’ only had machine guns.

Training

In June 1916, the arrival of the first Mark I tanks enabled the crews to get to grips with their new machines. Each man learnt his role - as gunner, loader or driver - and also learnt basic maintenance. This was all done in the strictest secrecy. The men told civilians in nearby Bury St Edmunds they were working on water cisterns or ‘tanks’ for the Russian Army.

On 26 July 1916, King George V inspected the tanks at Elveden, and was given a bumpy ride in one. By the end of the month General Sir Douglas Haig had decided the first group of tanks would go to France to assist in the Somme Offensive, which had started on 1 July 1916.

Off to France

In mid-August 1916, C and D Companies set off for France with their tanks. Known as Operation Alpaca, it was a great success and the tanks arrived safely.

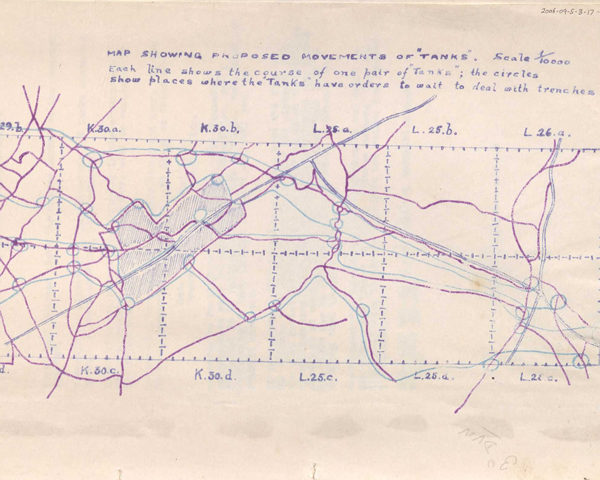

After further secret training behind the lines, it was decided that the tank would make its debut in support of the Fourth Army. Forty-nine tanks of the Heavy Section would join the attack on the village of Flers-Courcellette on 15 September 1916.

Amid great secrecy, the tanks were moved up to the line. But their presence could not be hidden from everyone. On 13 September, Gunner A Roads of the Royal Garrison Artillery noted: ‘Another “Big Do” being prepared. Saw armoured caterpillars going up to frontline.’

Into battle

To assist the six divisions involved in the attack, the tanks were broken up into small groups. They would lead the assault, destroying strong-points, machine-gun emplacements, wire and dugouts, and allow the infantry behind to push on and secure their objectives.

Prior to Zero Hour on 15 September 1916, the tanks made their way to the start line. But several broke down and were unable to continue. When the attack commenced only 15 out of 49 moved into no-mans land.

No breakthrough

These machines made a great impact on the Bavarian troops facing them, many of whom were terrified. A few tanks were able to advance far into the enemy defences.

These were gradually reduced in number by breakdowns and enemy action. Flers was captured but, despite the bravery of the crews, a total breakthrough eluded the tanks.

Co-operation

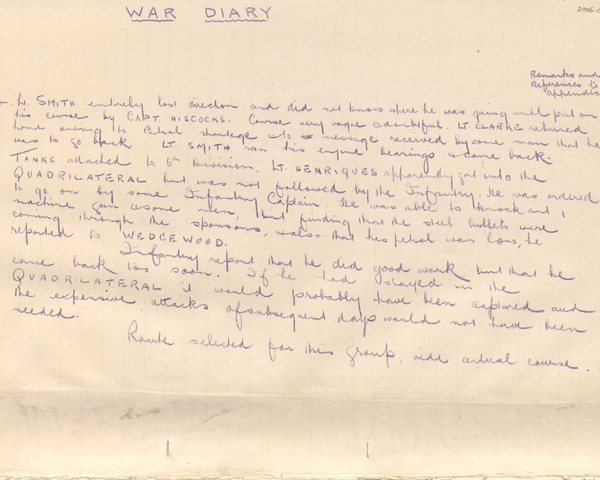

One of the main problems was co-ordinating the tank and infantry operations. One tank, C22, made it to a strong point in the German line known as the Quadrilateral, but struggled under enemy fire and was withdrawn.

‘Infantry report that he [the commander of C22] did good work, but that he came back too soon. If he had stayed in the Quadrilateral it probably would have been captured and the extensive attacks for subsequent days would not have been needed.’War Diary of Nos. 2, 3 and 4 Sections, C Company, Machine Gun Corps (Heavy Section) — 15 September 1916

Despite the shock to the Germans of encountering tanks for the first time, the overall aim of Flers had failed. Some tank officers later felt that too few tanks with hastily trained men had been thrown into the attack, and the key element of surprise had been wasted.

Tactical changes

Tanks were used again in November 1916 at the Battle of the Ancre. In an attempt to find a way to exploit the weapon, new methods were adopted. The heavy losses on the first day of the Somme had led the British to experiment with new tactics. By September, artillery and infantry were working in coalition, with troops advancing behind a creeping barrage. Unfortunately, the use of tanks caused problems with this method.

At Flers, large gaps were left in the bombardment to make way for the machines, meaning that enemy defences were left intact. In other places, such as High Wood, infantry overtook the slow-moving tanks and found themselves trapped in heavy machine-gun fire, suffering huge losses in the process.

Battle of the Ancre

At Ancre, it was decided that the tanks would follow the infantry. This would retain the integrity of the artillery fire, allowing troops to push forward. In instructions to troops it was emphasised that ‘the infantry will not wait for the tanks’ .

This meant that the tanks would instead mop up after the infantry, clearing leftover machine guns and strong points. To retain the element of surprise, the artillery were ordered to cover with shell fire the noise of the tanks making their way to the front line.

Unfortunately, the tanks themselves were still slow, cumbersome and prone to technical problems. And in the glutinous November Somme mud, they were also vulnerable to getting stuck.

‘I attribute the fact of the tanks failing to gain their objective to the extraordinary bad ground they had to cross which was worse than I imagined possible.’Report by Captain Richard Clively on the tank operations — 15 November 1916

Later battles

Tanks would be used again at Arras and Passchendaele in the spring and summer of 1917. But it was at Cambrai in November of that year that tanks were used in massed numbers for the first time.

They very nearly achieved the elusive breakthrough. But without adequate infantry reinforcements they could not exploit the gap created in the German line.

Anti-tank weapons

As well as struggling with rough terrain and erratic engines, the tanks were vulnerable to enemy artillery, airpower and anti-tank weapons.

The first generation of these was developed by the Germans in response to the appearance of the tank on the battlefield.

They used special armour-piercing bullets to penetrate the thick steel hulls.

All arms

By 1918, the tank had become part of a complex all arms battle-plan, using aircraft, artillery and infantry tactics together to ensure victory.

But in later years, despite a few British thinkers promoting the tank, it would be the Germans who used them to greatest effect in the Second World War during the Blitzkriegs of 1939-41.