Obliged to serve

During times of war, Britain has long relied on soldiers on home soil to ease the fear of invasion. As far back as Anglo-Saxon times, able-bodied men were bound to serve in a militia army called the 'fyrd', mobilised usually as a reaction to raids by Vikings.

The 'fyrd' comprised a core of experienced soldiers supplemented by ordinary villagers and farmers. Its function was to defend local lands from invaders. They were not full-time fighters, but bound to serve when the king needed them. Men could be fined if they neglected service in the 'fyrd' on being called up.

The demise of the militia?

The decay of feudal life in Britain during the 16th and 17th centuries led to a rise in mercenary soldiers who could be paid to fight.

This might have resulted in locally conscripted civilian militiamen no longer playing a part in defence. But the British Civil Wars (1639-52), followed by the reign and deposition of King James II in 1688, showed how a centralised army could be exploited as an instrument of royal tyranny or political revolution.

A civilian institution

The part-time militia was preserved as a counter to a small professional army that had to be sanctioned by Parliament. It became an increasingly important institution in civilian life.

The Militia Act of 1757 further transformed these men into a better-trained and better-equipped national force, organised by county.

Local force

The militia remained local in character. Militia officers were gentlemen chosen by the local landowner. But ordinary militia soldiers were local farmers, tradesmen and labourers. They were conscripted by ballot from their own communities - unless they could produce a substitute - to serve for five years.

Uniforms and weapons were provided and regiments were assembled for training and to deal with civil disturbance. The sheer number of eligible men obliged to serve in the militia meant that many more ordinary civilians had experience of military service than they do today.

‘In the year 1803 I drawn as a soldier for the Army of Reserve. Thus… I was drafted into the 66th Regiment, bid good-bye to my shepherd companions, and was obliged to leave my father without an assistant to collect his flocks… My father tried to buy me off, and would have persuaded the sergeant of the 66th that I was of no use as a soldier, from having maimed my right hand by breaking the fore-finger when a child. The sergeant, however, said I was just the sort of chap he wanted, and off he went, carrying me amongst a batch of recruits he had collected.’Rifleman Benjamin Harris recalling his recruitment to the militia — 1848

French threat

Militia units were fully assembled - or embodied - on a permanent footing during the Wars of the French Revolution (1793-1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). Troops were stationed at strategic locations, especially along the south coast to allay the fear of French invasion.

In Ireland, the use of militia units also grew. In the space of a few years, the number of part-time soldiers expanded from 14,000 to over 80,000 men. When rebellion broke out in Ireland in 1798, the militia played a leading role in its bloody suppression and in opposing the French landing on the west coast.

Policing unrest

Major social unrest among the industrial and rural poor presented a further problem for the establishment. In the pursuit of political representation and economic reform, food riots, machine wrecking and strikes became widespread.

By 1812, there were 12,000 soldiers in the most disturbed counties of Nottinghamshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire. Anti-militia conscription riots frequently followed the widespread popular unrest.

Yeomanry

Alarm at the prospect of rank-and-file militiamen turning against the military authorities in part prompted the creation of other back-up units.

The yeomanry, a mounted force drawn from the upper classes, was created at the peak of the fear of French invasion and used extensively in support of the civil authority to put down riots and disturbances.

Relatively ineffective as a military force, the yeomanry's main job was to suppress political and social unrest. They undertook this task with a brutal vigour that earned them the hatred of many.

An attractive option?

Even when embodied, day-to-day militia camp commitments were not onerous. Reviews held in summer drew great local interest, becoming part of the social calendar and providing opportunities for local tradesmen. The troops would spend a day marching, drilling and firing at targets for the entertainment of gathered crowds.

Only occasionally did militia soldiers get drafted into the army - although there were bounties offered to men who opted to become regulars - and it was a step that caused resentment in rural communities.

End of compulsion

Although muster rolls were prepared as late as 1820, compulsory obligation to serve in the militia was abandoned in the early 19th century. Those who joined would return to their day jobs after initial training, subsequently reporting only for extra instruction and the two-week camp every year.

There was never an obligation for militia to serve overseas like regular soldiers sent on active service, and for all ranks it was a relatively soft option in comparison.

The militia still appealed to agricultural labourers and men in casual occupations who could leave their civilian job and pick it up again. And the pay they received could be a useful top-up of their usual wages.

Easing the pressure

The strain on the regular army stationed on garrison duty around the world had become clear during the Crimean War (1854-56) and the Indian Mutiny (1857-59).

Troop shortages and patriotic zest during the imperial crises and expansion of the British Empire in the second half of the 19th century prompted the creation of other volunteer and yeomanry units, such as the Volunteer Force, with a far less distinct role, as well as the permanent embodiment of the militia in vulnerable British towns.

New legislation allowed more men to enter the army from the militia. By 1880, it was accepted that the militia now acted as a drafting body. It was no longer a citizen army designed to keep the regular army small and military despotism in check.

Territorials

The militia was transformed into the Special Reserve by a reforming Liberal government under the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act of 1907.

During the First World War (1914-18), the Special Reserve guarded vulnerable points in Britain and acted as a training and drafting body for the army, supplying replacements for soldiers posted overseas.

The legislation also merged the other reserve forces. The Volunteer Force joined with the yeomanry to form the Territorial Force, reformed later as the Territorial Army. We know the descendant force as the Army Reserve today.

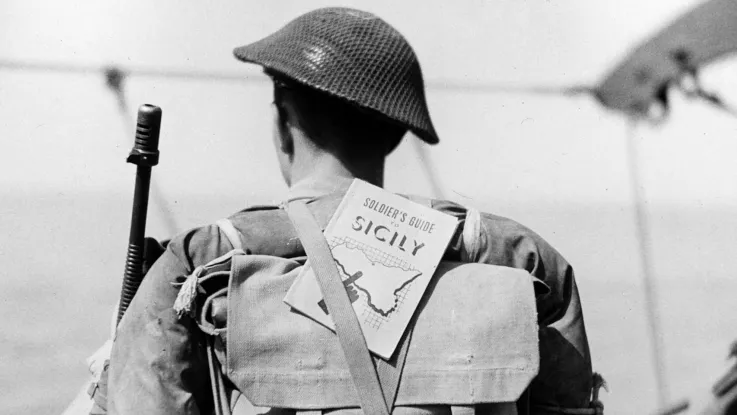

Territorials were not obliged to serve overseas. But when asked in August 1914, the vast majority agreed to do so.

Home Guard

Fear of invasion has dominated the trajectory of citizen soldiering in Britain. For example, the Home Guard, initially called the Local Defence Volunteers, was established during the Second World War (1939-45) to protect against possible German attack.

In May 1940, Anthony Eden, the Secretary of State for War, broadcast to ‘men of all ages who wish to do something for the defence of their country’ encouraging them to join. Within 24 hours 250,000 men had registered.

Dad’s Army?

The Local Defence Volunteers comprised ordinary citizens who were otherwise ineligible for military service. Nicknamed ‘Dad’s Army’, many of them were veterans, but a significant number were 17-year-olds waiting to be called up.

Others worked in jobs that were necessary to keep the country running, such as railway workers, bank staff and teachers. They were poorly armed and trained in the evenings in weapons handling, unarmed combat and basic sabotage.

Extra ears and eyes

In July 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill instructed that the volunteers should receive proper military training so that they could act as extra ‘ears and eyes’ for full-time soldiers.

The ‘Home Guard Handbook’ published in 1940 identified that a Home Guardsman was expected to know ‘the whole of the ground in his own district’.

Key fact

At its peak, the Home Guard numbered 1,793,000. It did not fall below one million until it was stood down at the end of 1944, as the threat of invasion began to fade. Around 1,200 Home Guardsmen were killed on duty or died from wounds during the Second World War.

‘The way it worked for the Territorial Army before, if you wanted to go on deployment, you’d go as a TA company and you do something called force protection, just basically like protecting an area. It’s not like doing war fighting or front-line infantry work; it’s kind of doing the jobs that the regular army don’t really want to do. And then, when HERRICK 10 came to our force, they didn’t want anyone to be doing force protection anymore. It was just you slotted in with the regular army. So, you just basically became a regular soldier and just did what they did.’Lance Corporal Thomas Saldanha, 7th Battalion The Rifles — 2012

Reserve service today

Reserve units were not called upon for either the Falklands War (1982) or to support the civil power in Northern Ireland during The Troubles (1969-2007). But today they play an increasingly critical role in British soldiering.

Following the reduction in size of the regular army as part of a strategic Army 2020 initiative, Britain will become more reliant on part-time soldiers in operations both at home and overseas. Anyone joining the Army Reserve now can expect to be mobilised for operational service within five years.

Army Reserve soldiers have recently been called upon for civil enforcement and as back up for environmental defence. Reservist soldiers who live and work in the same place are valuable because they have local knowledge that is useful in flood relief and emergency work. They can also be deployed quickly in their own communities.

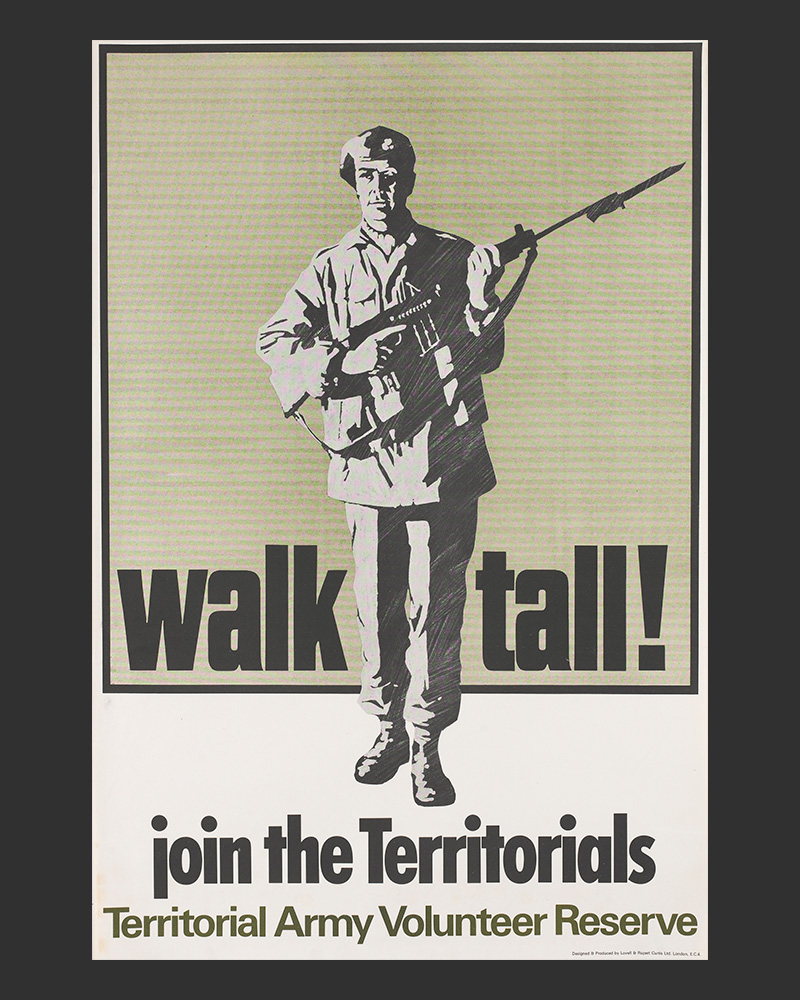

Territorial Army recruiting poster, c1967