Russian menace

The Crimean War started with Russia’s invasion of the Turkish Danubian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (now Romania). Britain and France both wanted to prop up the ailing Ottoman Empire and resist Russian expansionism in the Near East.

Although Russia fought a largely successful war against the Turks in Armenia, and British and French fleets operated in the Baltic Sea, it was the events in the Crimea that had the biggest impact on Britain.

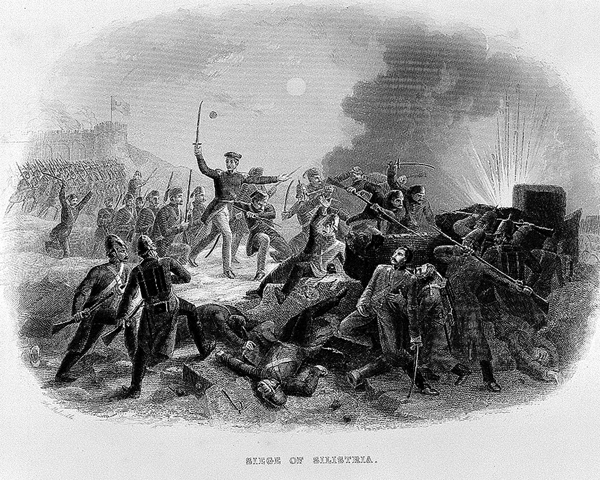

Allies intervene

In June 1854, British and French armies concentrated at Varna on the Black Sea with a view to supporting the Turks. However, the Russians were defeated by Ottoman Turkey at Silistria in the summer of 1854 and, under pressure from Austria, evacuated the disputed provinces. This made the British and French presence at Varna largely redundant.

Nevertheless, the British government, influenced by public opinion at home, decided that the Russian naval base at Sevastopol should be attacked instead. The French agreed. And on 14 September, the Allies landed on the north-west coast of the Crimea at Calamita Bay.

Map of the Crimea and the Black Sea, 1854

The Alma

By 18 September, 30,000 French under Marshal St Arnaud, 26,000 British under General Lord Raglan, and 4,500 Turks had been landed. Despite outbreaks of cholera among the troops, the Allies marched south on Sevastopol.

Blocking the way was a Russian force under Prince Alexander Sergeievich Menshikoff, which had taken up a strong position on the heights above the River Alma.

On 20 September, the Allies attacked and, despite confused leadership, the British stormed the main Russian position. The Russians retreated, having lost 5,000 men. The Allies had lost 3,000.

Missed opportunity

The way to Sevastopol was now open. But, unaware of the weakness of its defences, the Allies decided to march around the city and besiege it from the south, using the harbours of Balaklava and Kamiech as bases.

This gave the Russians time to strengthen Sevastopol’s fortifications, which stood up well to an initial bombardment commencing on 17 October.

Balaklava

On 25 October, Menshikoff mounted an attack with about 25,000 men in the direction of the British supply port of Balaklava and captured a number of Turkish redoubts. Pressing on towards Balaklava, a Russian cavalry force was checked by the fire of Major-General Sir Colin Campbell's Highland Brigade, the famous ‘thin red line’.

Commanded by Major-General Sir James Scarlett, the British Heavy Cavalry Brigade then charged and drove back the retreating Russian cavalry, which outnumbered them by more than three-to-one.

Menshikoff’s attack had run out of steam. Preparing to withdraw, the Russians began to remove the guns from the redoubts they had captured.

Charge of the Light Brigade

Seeing this from his position on high ground, Lord Raglan sent a loosely worded order instructing the cavalry ‘to advance rapidly to the front, follow the enemy and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns’.

However, Lord Lucan, the cavalry commander, and Lord Cardigan, commander of the Light Brigade, did not have the same view as Raglan. The only guns visible from their position were Russian ones at the end of a shallow valley. Cardigan proceeded to lead his Light Brigade in a fateful charge against them.

In an act of reckless bravery, 247 of Cardigan's 673 men were killed or wounded. Losses would probably have been even higher had the French Chasseurs d’Afrique not executed a brilliant charge to help the survivors withdraw.

The Russians had failed to take Balaklava, but they now overlooked the only road running from the port to the British siege lines at Sevastopol.

‘We advanced down a gradual descent of more than three-quarters of a mile, with the batteries vomiting forth upon us shells and shot, round and grape, with one battery on our right flank and another on the left, and all the intermediate ground covered with the Russian riflemen.’Lord Cardigan, describing the charge — 1854

Inkerman

On 5 November 1854, the Russians tried again. This time, they launched a surprise dawn attack on the British positions at Inkerman using troops from their field army and the Sevastopol garrison.

The battle was a confused affair, fought in thick fog. The British won thanks to the dogged determination of their infantry, who were supported as the day went on by French reinforcements. The British suffered 2,500 killed and the French 1,700. Russians losses amounted to 12,000.

Winter

The winter of 1854-55 became a nightmare for the British. On 14 November, a great storm swept the Crimea. The tents at the Allied camp outside Sevastopol were destroyed.

Several British ships were wrecked, including the steamship HMS ‘Prince’, which was carrying warm winter clothing and hay for the Commissariat’s horses. Altogether, 30 vessels with their precious cargoes of medical supplies, food and clothing were damaged.

Transport collapse

Having lost much of their fodder, the Army’s transport animals soon fell victim to cold and hunger. To make matters worse, the onset of winter had turned the earthen track between Balaklava and Sevastopol into a quagmire. Without adequate transport, the Commissariat was unable to move supplies to the men who needed them desperately.

In the worst of the winter, with wheeled transport unable to negotiate the boggy road and most of the horses dead, soldiers were forced to walk the 19km (12 miles) round journey to Balaklava in order to collect supplies.

Freezing trenches

The troops in the trenches outside Sevastopol soon ran short of rations, winter clothes, tents, medical supplies and fuel for cooking. Poorly clothed, lacking shelter and succumbing to disease, by February 1855 the British force had been reduced to 12,000 effective men.

‘We are now about three miles from Sebastopol and under canvas tents, the rain pouring in torrents and all around miserable. Cholera has broke out amongst the poor fellows who are exposed in the trenches day and night with nothing but their big coats to shelter them from the rain or cold... We get biscuits salt pork or beef and one gill of rum with some sugar rice and unroasted coffee. Just like our government, the idea of sending coffee here not roasted. We manage it somehow, by grinding it in a broken bombshell with a round shot to crush it. Water is very scarce and extremely muddy. I have not washed my face nor yet shaved since I landed here... being satisfied with enough to drink without washing my face and as for a clean shirt I think when I can find it convenient to wash one then I will put one on... This terrible Cholera... has made fearful ravages here. I have just commenced to write again and there are now six poor fellows lying dead. I am rather loose in my bowels, but take as much care of myself as possible.’Letter by Sergeant Frederick Newman, 97th Regiment, who died of fever two weeks after posting it — November 1854

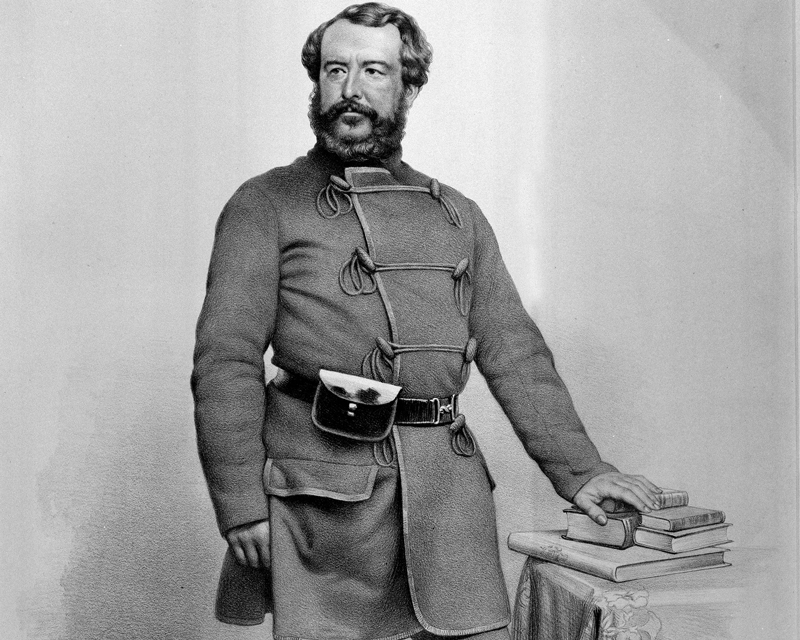

War reporting

There was nothing particularly new about these problems. Almost every British overseas expedition in history had suffered similar issues. But the Crimean War was the first campaign to be reported on by a war correspondent.

William Howard Russell of 'The Times' sent home shocking accounts of the Army’s shortcomings. The ensuing outcry led to the fall of Lord Aberdeen’s government.

Medical neglect

Short of shipping space, the British had brought only a few ambulances with them to the Crimea. With the transport animals dying of hunger in ever growing numbers, even these were not available to take the sick and wounded to Balaklava, where they could embark for Scutari, a suburb of Constantinople. Things got so bad that the British were forced to borrow French mules or use their cavalry horses to carry patients.

Those who managed to get back to Balaklava, and then survive the voyage to Constantinople (now Istanbul), found the hospitals at Scutari ill-equipped and the medical staff overwhelmed. Men sometimes lay untreated for weeks.

‘They were with few exceptions in a truly pitiable state of filth and utterly helpless from wounds and debility. On being brought inside the hospital several were found to be dead, many were at their last gasp, and others it was evident had but a short time to live. Almost all the living... were swarming with vermin, huge lice crawling all about their persons and clothes. Many were grimed with mud, dirt, blood etc and gunpowder stains. Several were more or less severely wounded and others were completely prostrated by fever and dysentery. The poor fellows endured their sufferings with heroic fortitude amounting in appearance to indifference to their fate… There has been somehow unaccountable neglect in the arrangements for this hospital. Until some hours after the arrival of the men there were neither stores, attendants nor the necessary refreshments on the spot. During this afternoon I attended single handed to the wounds and wants of 74 helpless men.’Journal of Acting Assistant Surgeon Henry Bellew, Army Medical Department — 1854

Re-organisation

Lord Palmerston’s new government appointed commissions of inquiry into the disaster. While recognising that the lack of a metalled road between Balaklava and Sevastopol had been a factor in the supply breakdown, the reports also criticised the government for not supplying adequate equipment and materials.

The inquiry also blamed senior Army officers for delays in distributing stores. In response to the findings, the government reorganised military administration, implemented plans for a Land Transport Corps and started building a railway at Balaklava. With these measures and the coming of Spring, the supply situation gradually improved.

Sanitary commission

Palmerston’s government also formed a commission to inquire into the sanitary condition of the Army. It consisted of Dr John Sutherland assisted by Dr H Gavin and Robert Rawlinson, a sanitary engineer.

They reached Constantinople in March 1855 and their work, alongside that of Florence Nightingale’s nurses, helped reduce the death rate in the hospital at Scutari by half within a matter of weeks.

Continuing on to the Crimea, the commission’s measures to overhaul sanitary conditions in the field hospitals and camps proved equally successful.

Nursing

The revelations from the Crimea also prompted the nursing work of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. Florence and her nurses improved the medical and sanitary arrangements at Scutari by setting up food kitchens, treating the wounded, cleaning the soldiers and washing their linen and clothes. Their work in the Crimea set the standards for modern professional nursing.

Aiding the wounded

Born in Jamaica to a Creole mother and a Scottish Army officer, Mary Seacole had travelled to London late in 1854 to volunteer her services as an Army nurse. Rejected by the War Office and Florence Nightingale, she paid her own passage to the war.

Famous for her homemade cures, she frequently rode out to dispense medicine and food to those in need. She was often on the front line and frequently under fire.

Although some of the Army doctors regarded her as a 'quack', others were more supportive and believed in her cures. Most of these were based on the use of traditional herbs, poultices and therapeutic rubs. If the soldiers could not afford to pay her, Mary subsidised them from her own pocket.

‘[She is] a warm and successful physician, who doctors and cures all manner of men with extraordinary success. She is always in attendance near the battlefield to aid the wounded, and has earned many a poor fellow's blessings.’William Howard Russell on Mary Seacole — 1856

Sevastopol

In the spring of 1855, preparations were resumed for the capture of Sevastopol. After a lengthy bombardment and the capture of some outworks, an assault was ordered for 18 June.

Redan

The British, many of whom were recently-arrived and inexperienced reinforcements, attacked a strongpoint known as the Redan. Forced to advance under heavy fire over 250 yards of open ground, they suffered over 1,500 casualties before falling back.

Malakoff

On 8 September 1855, the Allies attacked again. For a second time, the British failed to take the Redan. But the French capture of the Malakoff redoubt, another key part of the defences, led to the Russians abandoning Sevastopol. Among the trophies taken from the port city were around a thousand guns. Many of these are still visible in towns and cities across Britain and the Commonwealth.

The Allies spent another winter in the Crimea. This time it was the French Army’s turn to be decimated by disease, while the British - by now well-clothed, housed and equipped - were spared the sufferings of the previous winter.

Peace

The Russians were shaken by the loss of Sevastopol. In October 1855, their mainland base of Kinburn also fell to the Allies. When the Austrians threatened to enter the war against them, the Russians agreed to peace terms and the Treaty of Paris was signed in March 1856.

One of the treaty's clauses was the neutralisation of the Black Sea and Dardanelles. This served as a blow to the Russian dream of a warm water naval port in the south.