Training and appointment

Born into a wealthy family, Florence overcame the narrow opportunities offered to girls of her station. In 1851, despite the disapproval of her family, she completed a course of nursing training in Germany.

Moved by newspaper accounts of soldiers' suffering in the Crimean War (1854-56), Florence answered a government appeal for nurses. She was soon appointed Superintendent of the Female Nurses in the Hospitals in the East.

Arrival at Scutari

On 21 October 1854, Florence and her party of nurses left London. They crossed the Channel and travelled through France to Marseilles. From there they sailed to Constantinople (now Istanbul), arriving on 3 November.

At Scutari, near Constantinople, the conditions were dire. The dirty and vermin-ridden hospital lacked even basic equipment and provisions. The medical staff were swamped by the large number of soldiers being shipped across the Black Sea from the war in the Crimea. More of these patients were suffering from disease than from battle wounds.

‘All were swarming with vermin, huge lice crawling all about their persons and clothes. Many were grimed with mud, dirt, blood and gunpowder stains. Several were completely prostrated by fever and dysentery. The sight was a pitiable one and such as I had never before witnessed... There has been somehow unaccountable neglect in the arrangements for this hospital. Until some hours after the arrival of the men there were neither stores, attendants nor the necessary refreshments on the spot. During this afternoon I attended single handed to the wounds and wants of 74 helpless men.’Assistant Surgeon Henry Bellew describing Scutari hospital — January 1855

Gradual acceptance

Despite these conditions, the male army doctors didn't want the help of Florence and her nurses. At first, they saw her opinions as an attack on their professionalism. But after fresh casualties arrived from the Battle of Inkerman in November 1854, the staff were soon fully stretched and accepted the nurses' aid.

Florence and her nurses improved the medical and sanitary arrangements, set up food kitchens, washed linen and clothes, wrote home on behalf of the soldiers, and introduced reading rooms.

The Lady with the Lamp

Florence gained the nickname 'the Lady with the Lamp' during her work at Scutari. 'The Times' reported that at night she would walk among the beds, checking the wounded men holding a light in her hand.

The image of 'the Lady with the Lamp' captured the public's imagination and Florence soon became a celebrity. One of the main creators of the Nightingale cult was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who immortalised her in his poem 'Santa Filomena'.

‘A Lady with a lamp shall stand. In the great history of the land, A noble type of good, Heroic Womanhood.’'Santa Filomena' by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow — 1857

Death rate

Florence and her nurses greatly improved the comfort of the men at Scutari. But, by February 1855, the death rate at the hospital had risen to 42 per cent. Florence mistakenly blamed the high number of deaths on inadequate nutrition, not on poor sanitation.

The unventilated building sat on top of a damaged sewer. The death rate only dropped after the sanitary commission repaired the sewers and improved the ventilation.

More help needed

In January 1855, Florence wrote to Lord Raglan, the British commander in the Crimea, pointing out deficiencies in medical arrangements for the sick and wounded at Scutari. She wrote about the lack of trained medical orderlies in the wards and pointed out that 'hundreds of lives may depend upon' addressing this situation.

Troubles and turmoils

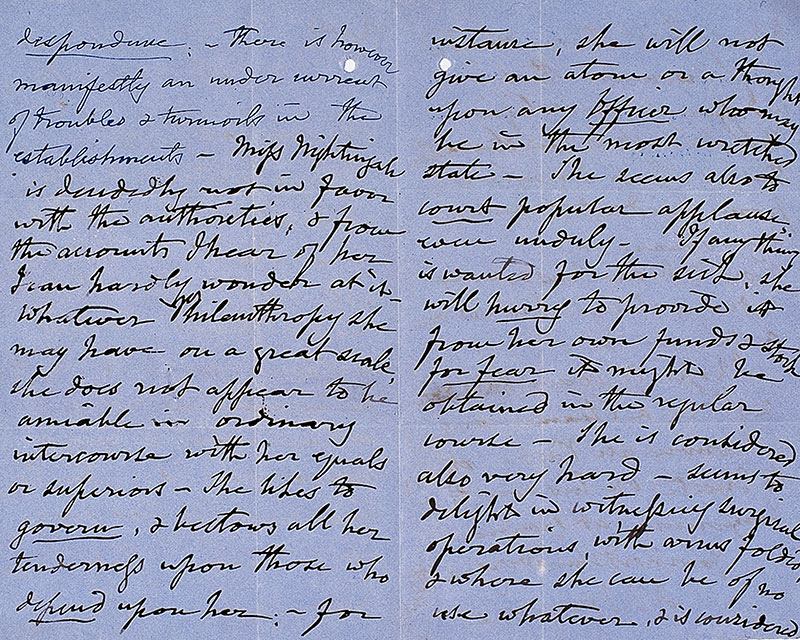

Lord Raglan was sympathetic, but others were less enthusiastic. General Sir John Burgoyne believed that although 'the hospitals appear to me to be in excellent order' and the patients content, there was 'an under current of troubles and turmoils'.

He felt that Florence did 'not appear to be amiable in ordinary intercourse with her equals or superiors. She likes to govern, and bestows all her tenderness upon those who depend upon her'.

Fever

On 2 May 1855, Florence left the hospital in Scutari in order to witness for herself the conditions of the army at Balaklava. Within a few days of her arrival in the harbour, she was struck down with 'Crimean fever'.

Although it was feared that she was near to death, Lord Raglan was able to telegraph London that she was out of danger by 24 May. However, her recovery was slow, hampered in part by her demanding schedule.

‘During the greater part of the day I have been without food necessarily, except a little brandy and water (you see I am taking to drinking like my comrades in the Army).’Florence Nightingale writing to Sidney Herbert, Secretary at War, during her illness — 1855

Crimean carriage

On returning to her duties, the exertion of travelling to far-flung field hospitals took its toll on Florence's delicate health. She was given a mule cart, but this overturned one night. Colonel William McMurdo of the Land Transport Corps presented her with her Crimean carriage, which also served as an ambulance.

Statistics

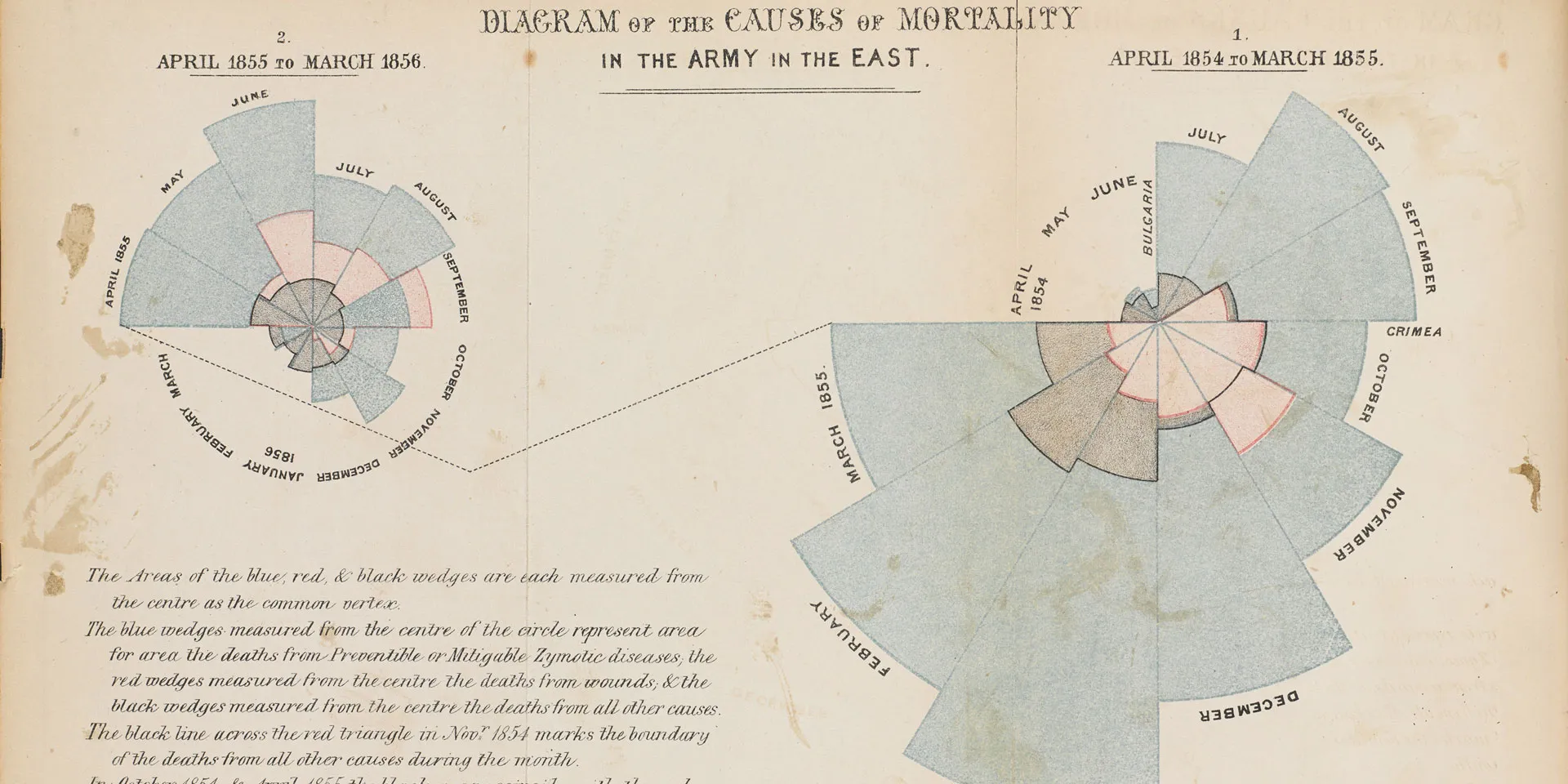

Florence was also a ground-breaking statistician. When she arrived at Scutari, the number of deaths was not being recorded appropriately. Her use of statistics cut through rumour and hearsay, while diagrams provided hard evidence in support of her recommendations for reforms in patient care.

Through data analysis, she found that soldiers were more likely to survive if they stayed in the hospitals at the front (which had a 12.5 per cent mortality rate) than if they were transferred to the hospital in Scutari (which had a 37.5 per cent mortality rate). In 1859, in recognition of her pioneering work, she was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society.

The chart below, which Florence included in one of her books, allowed multiple data comparisons in one diagram. It clearly demonstrated that more soldiers had died in the Crimea in 1855-56 from disease (shown in blue) than from wounds (shown in red).

Nightingale Training School

Florence returned to England in August 1856. In the years that followed, she continued to campaign for the reform of nursing and for cleaner hospitals.

By 1859, well-wishers had donated over £40,000 to the Nightingale Fund. Florence used this money to set up the Nightingale Training School at St Thomas's Hospital on 9 July 1860.

Once the nurses were trained, they were sent to hospitals all over Britain, where they introduced her ideas. Florence also published two books, 'Notes on Hospital' (1859) and 'Notes on Nursing' (1859), that laid the foundations of modern nursing practice.

Recognition and adulation

Florence was showered with awards and decorations in recognition of her work. She became a national icon.

Her contemporary fame was reflected in the production of merchandise commemorating her achievements. Florence herself was publicity-shy and was appalled at the adulation she received. But this did not prevent the development of a whole industry based on her celebrity.

Queen Victoria herself awarded Florence a jewelled brooch, designed by her husband, Prince Albert. It was dedicated: 'To Miss Florence Nightingale, as a mark of esteem and gratitude for her devotion towards the Queen's brave soldiers.’

Florence Nightingale was the first of eight women to receive the Order of Merit. The highly prestigious Order's membership is limited to the Sovereign and a maximum of 24 others at any one time.

Later life

Florence later suffered from what is now known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Despite being bedridden for many years, she still campaigned tirelessly to improve health standards.

She died on 13 August 1910 aged 90. Her relatives declined the offer of burial in Westminster Abbey. She was instead buried at St Margaret's Church in East Wellow, near her parents' home.

Legacy

Before Florence Nightingale, nursing was not considered a respectable profession. With the exception of nuns, the women who worked as nurses were often ill-trained and poorly disciplined. Most were working-class. Florence was determined to encourage educated, 'respectable' women into nursing.

Her work in the Crimea set the standards for modern nursing and helped transform its public image.