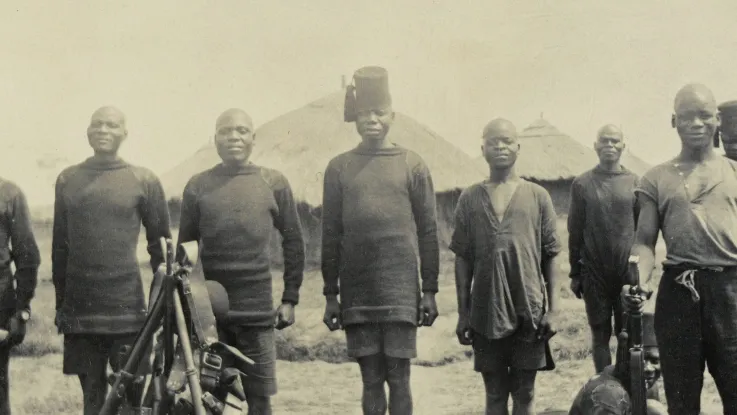

Askaris

On the outbreak of war in 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck was the commander of a small army in German East Africa (now Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda). He was determined to tie down as many Allied troops as he could in the region to prevent them from being deployed elsewhere.

With an army that never numbered more than around 14,000 men - comprising about 3,000 Germans and 11,000 askaris (African soldiers) - he succeeded in occupying ten times that number of Allied troops.

‘With the means available, protection of the Colony could not be ensured even by purely defensive tactics... it followed that it was necessary, not to split up our small available forces in local defence, but... to keep them together, to grip the enemy by the throat and force him to employ his forces for self-defence.’General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, 'My Reminiscences of East Africa' — 1920

Defeat at Tanga

In August 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck raided British positions around Mount Kiliminjaro and Lake Victoria in British East Africa (Kenya). In response, a British-Indian force under Major-General Arthur Aitken landed near the German East African port of Tanga on 3 November 1914. Aitken made no attempt at concealing his plans and Lettow-Vorbeck was given time to reinforce his defences.

When they came under fire, Aitken’s poorly trained Indian troops panicked and ran. Although they were outnumbered, the Germans counter-attacked. Aitken’s troops were driven back to their boats, where they re-embarked on 5 November.

At a cost of 150 casualties, Lettow-Vorbeck had inflicted 850 casualties and captured hundreds of rifles and machine guns, and 600,000 rounds of ammunition. The supplies left behind helped equip his army for the next year.

‘We were trying to land and when inside the harbour the Germans opened fire from guns which are supposed to have been landed off the “Konigsberg”… We went in with bands playing only to be mown down… Tanga was practically empty, the Germans on being asked to surrender got 12 hours – not having got their defences perfected and men down from up country asked for 12 hours more and got it! Then they allowed our chaps to walk in with disastrous results. We lost 2 batteries, 12 maxims, 1 million rounds, rifles and goods galore... Unless something strange happens it will not be a walk over taking German East Africa.’Letter from an unknown officer at Tanga to General Sir Stanley De Burgh Edwardes — 20 November 1914

Raids

Britain commanded the sea and was able to send reinforcements. Lettow-Vorbeck, heavily outnumbered and with limited resources, switched to a guerrilla campaign, mounting raids in Kenya and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).

At the same time, the German cruiser ‘Königsberg’ attacked Allied shipping off the coast. She was eventually sunk in July 1915.

New offensive

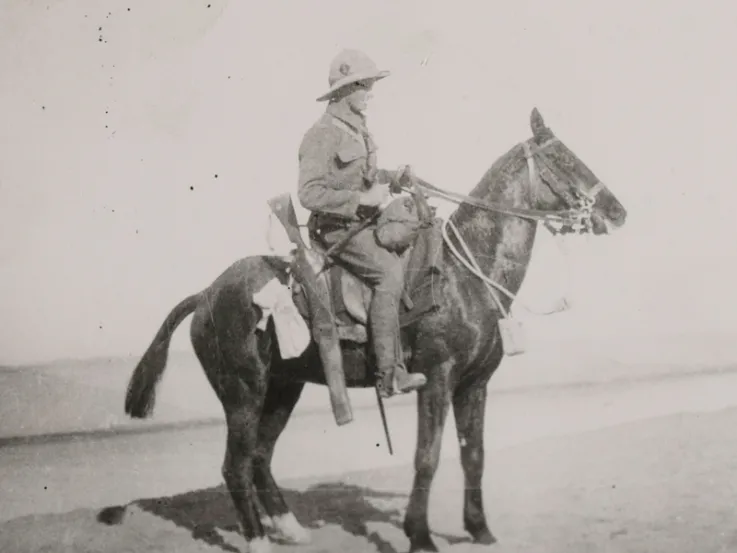

In March 1916, General Jan Smuts assumed command of the Allied forces. He brought with him South African troops who were now available following the conquest of German South-West Africa (now Namibia).

A large Carrier Corps of African porters carried supplies for Smuts into the interior, much of which lacked railways or roads. Smuts himself was an old hand at this type of warfare, having fought against the British in the Boer War (1899-1902).

In May 1916, Smuts attacked from the north out of Kenya, while troops from the Belgian Congo (now part of Democratic Republic of the Congo) advanced from the west. A column also advanced from Northern Rhodesia in the south-west.

By August 1916, Smuts had captured the railway line from Dar es Salaam to Morogoro and Dodoma. Despite this, Lettow-Vorbeck always managed to disengage his forces before they were overwhelmed, fighting a series of rearguard skirmishes and carrying out many ambushes.

‘When marching along the road the Germans opened on us with maxims. Our “cow” guns as they are called – because they are pulled by cattle – came up and after about 40 shells shifted the Germans… I went out afterwards and brought in two wounded German askaris… The country here is so mountainous that it is very easy for the Germans to leave a small rearguard to hold us up… The scenery is magnificent. Huge tree ferns all along the valleys and the hills covered with thick bush which you can’t get through without cutting down... We also marched through a succession of swamps… and pushed on up a steep pass through the mountains. Our men had just got to the top when they were fired on and for a time there was a regular duel… We had two men hit. Altogether in three days scrapping we have had about 40 casualties. We pushed on another two miles, the Germans trying to stop us. We had to lie down every now and again when they were firing… We then went on and got to a small mission flying a Red Cross flag. In it we found 15 Germans and 34 askaris, most of them sick… All the Germans said they were tired of the war but that they were going to hold out until the very end. Most were from the crew of the Konigsberg. I never dreamt we should have this sort of warfare here… We get lots of queer food (beans etc) which we raid from the surrounding villages – the inhabitants having all cleared out.’Letter from Captain Alexander Wallace to his fiancée — 6-13 September 1916

Disease

Many troops suffered from the climate and tropical diseases. One unit, the 9th South African Infantry, began the campaign with 1,135 men in February 1916. By October, it was down to 116, having hardly engaged the enemy.

For every man the Allies lost in battle, a further 30 were lost through sickness. Lettow-Vorbeck’s askaris, on the other hand, were more resistant to local diseases.

Africans take over

At this time, Smuts began to withdraw many of his South African, Rhodesian and Indian troops and replace them with Africans from the King’s African Rifles, Gold Coast and Nigerian Regiments, who were more resistant to the climate and local diseases.

By November 1918, the ‘British Army’ was mainly composed of African soldiers.

Confined

By the end of 1916, the Germans were confined to the southern part of German East Africa. Early in 1917, new moves were made against Lettow-Vorbeck from Kenya, Nyasaland (now Malawi) and the Belgian Congo.

His forces divided into three groups. Two of them managed to escape the offensives. But the third, of around 5,000 men, was forced to surrender.

‘We moved at dawn, proceeding slowly through the bush. We had only gone a few hundred yards when our scouts suddenly came on the Germans… Their main body opened out and came for us. There was a lot of firing for a bit… We had rather a rush to get away. The bullets were coming rather close... While we were lying in our hole some Germans got behind us and we felt rather uncomfortable until some of our men dropped back behind us. The fight went on for two hours and ended in the rout of the Germans… I believe the Rhodesians made a bayonet charge which settled things, but we have had some good men killed. The Germans seem to be a plucky lot. There was a white man on each maxim and they were all bayoneted at their guns… The German askari were Nubians whom our men said were wonderful fighters. We buried 45 Germans and next morning they sent in a white flag saying they were leaving 40 wounded for us. Our casualties were under 30.’Letter from Captain Alexander Wallace to his fiancée — 14 November 1916

Final moves

As the British closed in, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed south into the Portuguese colony of Mozambique. Small detachments of Germans attempted to join him there. The British columns continued to pursue these for the remainder of the war, engaging in a series of skirmishes.

Both sides were continually hampered by logistical problems and food shortages. Medical provisions were basic.

Although groups of Germans began to give themselves up, Lettow-Vorbeck was still raiding in 1918 when he learned of the Armistice, reputedly from a British prisoner. On 25 November 1918, he surrendered his unbeaten force - now reduced to about 1,500 men - to the British in Northern Rhodesia.

‘I got 41 wounded off yesterday, but still have 20 serious cases, mostly askaris. Their wounds are all very septic and it takes a long time to dress them. I hope to get the others off in a few days. There is difficulty in getting carriers for them… This is rather a filthy camp [and] the flies are simply swarming. There are also a lot of mosquitoes.’Letter from Captain Alexander Wallace to his fiancée — 7 September 1917

Cost

During the East Africa campaign, British Empire forces lost over 10,000 men. German losses were about 2,000.

East Africans suffered the most. One estimate is that around 100,000 carriers and camp followers died on both sides. There were also thousands of civilian casualties.

‘There will be a lot of starvation… The Belgians told us that last year in the Rwanda country – between Lakes Tanganyika and Nyasa – 20,000 natives died of starvation. War is a sad thing for the native population. The troops occupy the country for a bit, take what food there is leaving nothing for the natives.’Letter from Captain Alexander Wallace to his fiancée — 10 December 1917

Discover more

Visit our Global Role gallery to delve deeper into the contribution of troops from across the African continent, as well as other Commonwealth soldiers, during the First World War.