Suez offensive

On 2 February 1915, Turkish forces in the Middle East attempted to breach British defences on the Suez Canal. Capturing this strategically vital channel would cut British communications with East Africa, India and Asia, and prevent British Empire troops from reaching the Mediterranean Sea and Europe.

The British had expected the offensive and were well prepared, having fortified the length of the Canal. The fighting lasted two days, with the Turks losing over 2,000 men. British losses were minimal.

Senussi revolt

Several months later, the Turks attempted to raise a rebellion among the Senussi tribesmen of British-controlled Egypt. This was eventually defeated by the Western Frontier Force and peace terms were agreed with the rebels.

Defence

Throughout 1915 and 1916, the British were content to guard the Suez Canal. But defeat at Gallipoli dashed any hope of a quick victory over the Ottoman Empire.

Defending the Canal from possible Turkish attack also required a level of manpower the Army could not sustain, especially with the ever-growing demand for troops on the Western Front.

‘27 December 1915 - We are situated in a pretty spot on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. The redoubt is built with sandbags and we are under canvas, while our front is barbed wire. We are away from anywhere but greatly enjoying it, as the sea is only a few yards away, presenting splendid bathing facilities. We patrol the banks of Suez at night… A wonderful sight are the search lights which every ship carries when passing through the canal. / 5 February 1916 - Laying cable through the desert to trenches. The light railway is well on its way towards completion… The desert is covered with dried shrubs and lizards and large rats abound. The only people we see are Indian lancers, whose duty is to patrol. Our food and water are brought up by camels, which we captured from the Turks in their last raid.’Diary of Private James Tait, The East Yorkshire Regiment — 1915-16

Sinai

Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Murray, commander of the newly formed Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), now decided to push the Turks out of the Sinai peninsula. This would reduce the threat to the Canal and force them to defend their own territory in southern Palestine.

During Spring 1916, the EEF cut Turkish routes to the Canal. By destroying wells and waterholes, they stopped the enemy from advancing across the desert. The British then occupied Romani in May 1916 to prevent it from being used as a base for Turkish raids.

In August 1916, a Turkish counter-attack at Romani was repulsed, marking the end of their campaign against the Suez Canal.

Crossing the desert

The Turks retreated. But if the British were to push them all the way back to Palestine, the EEF would have to cross hundreds of miles of desert. In February 1916, construction began on a railway and water pipeline, which would eventually stretch to the Palestine border.

Egyptian help

Even while under construction, the railway could still carry men and supplies forward. The same was not true for the pipeline. The men working on it, and indeed the mounted troops providing protection and diversion from Turkish raids during construction, needed a separate water supply.

Support came from the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps. Between 1916 and the end of the campaign in 1918, 170,000 Egyptian volunteers with their 72,500 camels transported water, as well as food and medical supplies, to the British front.

Sinai secured

The EEF finally reached eastern Sinai in December 1916. On 23 December, it defeated the Turks at the Battle of Magdhaba, forcing them from their forward base of El Arish.

British and Anzac troops of the mobile Desert Column then attacked the Turks at Rafa on 9 January 1917. After overcoming tough resistance and well-constructed fortifications, they captured the border town and 1,500 enemy troops. This victory expelled the Turks from Sinai.

Murray replaced

Under political pressure to win a quick victory following the losses suffered on the Western Front in 1916, Murray launched two unsuccessful attacks on Gaza in March and April 1917. Had he been given time to build up his forces and supplies, he may have succeeded. But failure saw him replaced as commander by General Sir Edmund Allenby in June.

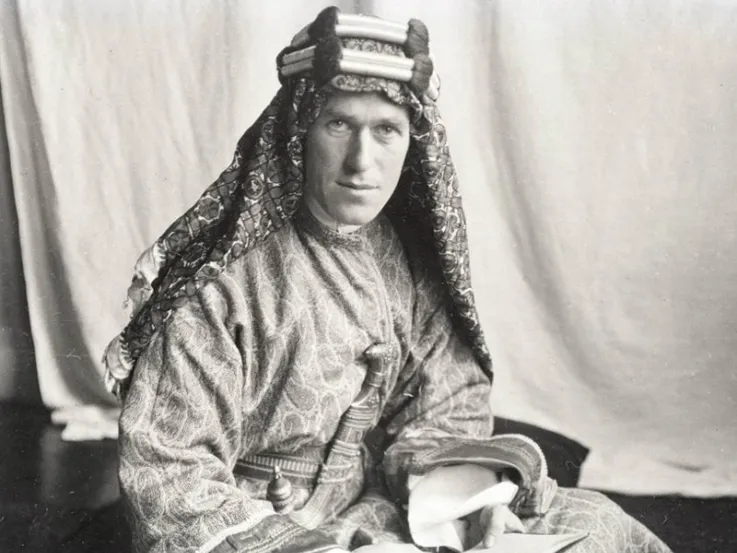

Allenby brought a greater vigour to the EEF. More importantly, he brought reinforcements at a time when Turkish strength was being whittled away by the Arab Revolt. This had started the previous June and was helping to undermine Turkish strength, partly through the efforts of Colonel TE Lawrence - now better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

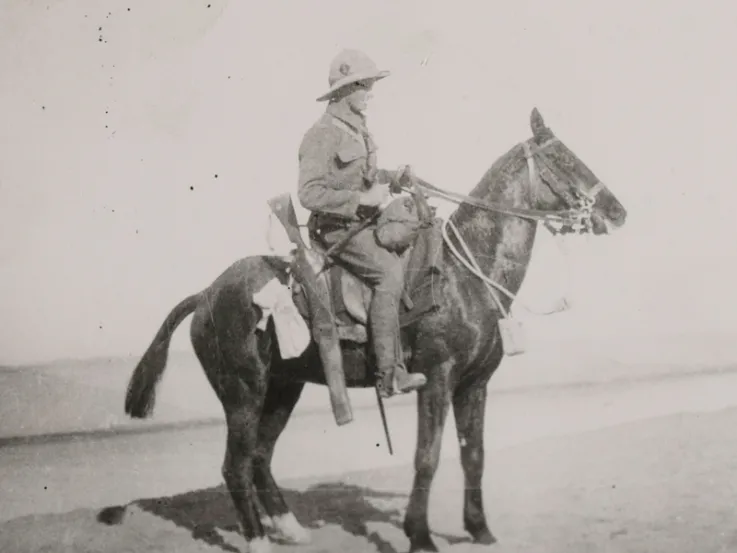

By October 1917, the British outnumbered the Turks by two-to-one in infantry and eight-to-one in cavalry in one of the few theatres of war where mounted troops could still be used effectively.

Advance on Gaza

To wrong-foot the Turks, Allenby now made a feint towards the heavily defended Gaza sector. He launched raids and regular bombardments there to keep the enemy’s attention, before launching his main attack further east against Beersheba (31 October 1917) on the northern edge of Sinai.

Allenby’s British Yeomanry, Australian and Indian cavalry units were particularly successful, driving deep into the desert.

The capture of Beersheba outflanked the Turks, who were forced to retreat. The Third Battle of Gaza (1-2 November) then began. And on 7 November 1917, Allenby entered the town.

‘Beersheba was captured with 1500 prisoners and 16 guns. Our casualties 900… All night Turkish artillery bombarded our trenches. They seemed to have been deceived as to the true point of our attack… [At] midnight, and twice again after, the Turks made strong counter-attacks which in each case were repulsed with heavy losses to them… We later found that the Turks had bolted… we are well on the way to Gaza itself and the cavalry are working round between Gaza and the sea.’Diary of Captain Walter Bagot-Chester, 3/3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles — 6-7 November 1917

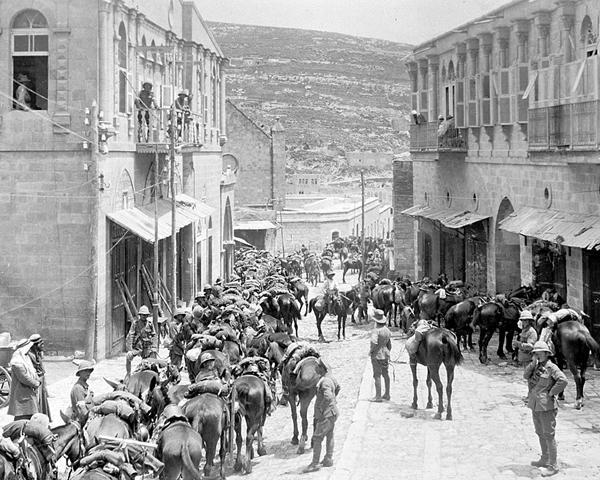

Jerusalem

Allenby pressed on. After defeating the Turks at the Battle of Mughar Ridge on 13 November 1917, he captured Jaffa three days later. His forces then pushed north. Following another successful offensive, he entered Jerusalem on 11 December 1917.

‘The taking of Jerusalem was a good performance by my troops... They had been marching and fighting hard since 31st October. As the supply situation would not allow more troops to be brought up for some days, I decided to attack to the north of Jerusalem, through the mountains, at once with what I had; risking counter-attack at Jaffa and Ludd. I sent the Yeomanry Mounted Division and two infantry divisions by the valleys of Beit Ur and Yalo and the Jerusalem Jaffa road. Their objective was Bire, to avoid fighting near the Holy City. On 20th the infantry gained the crest of the range; and the Turks were well up on their left. However, they could not get further; and it was not until I could relieve them by fresh troops, and get up some guns, that I was able to complete the isolation of Jerusalem. The mountains are barren, stony and roadless; a mass of rocky peaks and precipices. If we had given the Turk time to organise a defence we should never have stormed the heights… I have now beaten 11 Turkish divisions. He has fought well, however, and still puts up stubborn resistance – though disorganised. I have taken over 12,000 prisoners and more than 100 guns.’Letter from General Sir Edmund Allenby to a colleague — 18 December 1917

Deception

Further advances were temporarily delayed as troops were transferred from Palestine to France in the wake of the German Spring Offensive. But in September 1918, Allenby attacked the Turks, who held a defensive line running from Jaffa to the River Jordan.

Once again, deception played its part in the operation. While Arab forces disrupted Turkish communications and aircraft bombed their headquarters, Allenby made a feint towards the Jordan Valley while secretly building up his forces on the coast.

Triumph at Megiddo

On 19 September 1918, following accurate artillery barrages, the infantry broke through at Sharon, pushing the Turks away from the sea. General Sir Henry Chauvel's Desert Mounted Corps poured through the gap.

They rode up the coast for 50km (30 miles), taking Haifa, before swinging inland to Megiddo to block the Turkish retreat. Waves of British and Australian aircraft repeatedly attacked Turkish forces as they withdrew.

Map of Palestine campaign, 1918

Victory

Ottoman opposition collapsed and Allenby swept on into Syria. Damascus fell on 1 October, and Aleppo on 23 October. At the end of the month, defeated in Mesopotamia and under pressure at Salonika, the Turks sued for peace.

In just over a month, Allenby had advanced 560km (350 miles) and taken 75,000 prisoners for the loss of 5,000 men.