Serbs defeated

Serbia was an ally of Britain and had successfully resisted the attacks of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the opening months of the First World War. But, in October 1915, the combined forces of Austria, Germany and Bulgaria overwhelmed her armies and conquered the country.

The Serbs retired through the mountains of Montenegro to Albania, losing over 200,000 men in the winter snow. The survivors were evacuated to the island of Corfu to regroup.

Aid delayed

Lack of resources and political indecision among the Allies led to delays in the dispatch of aid to Serbia until it was effectively too late to help. It was eventually agreed to land forces at the vital port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki) in the northern Greek region of Macedonia.

Greece was neutral and in some political turmoil. King Constantine was pro-German, while his prime minister, Eleutherios Venizelos, supported the Allies.

French forces and Lieutenant-General Sir Bryan Mahon’s 10th (Irish) Division, exhausted after service at Gallipoli, began landing at Salonika on 5 October 1915.

Freezing winter

The 10th Division eventually went into the line in the mountains around Kosturino in November as the Allies attempted to block the Bulgarian advance. Unfortunately, the troops had not been equipped for a winter campaign in difficult mountain terrain. By the end of November, more than 1,600 men had been evacuated from the division, many suffering from frostbite.

‘Very bad night – no shelter from the cold and wet. I had a rotten passage round the line, falling and stumbling about in snow drifts up to my shoulders in some places. The snow kept on falling yesterday evening and part of the night, and then changed to a most intense frost. This morning everything is frozen hard and every track is too slippery to walk on… Our overcoats are frozen hard, and when some of the men tried to beat theirs to make them pliable to lie down in they split like matchwood. The men can hardly hold their rifles as their hands freeze to the cold metal. Everyone is falling and tumbling about in the most ludicrous way… We had an enormous sick parade this morning nearly 150 men reporting. There are many bad cases of frost bite in hands and feet.’Diary of Captain Noel Drury, 6th Battalion The Royal Dublin Fusiliers — 27-28 November 1915

Battle of Kosturino

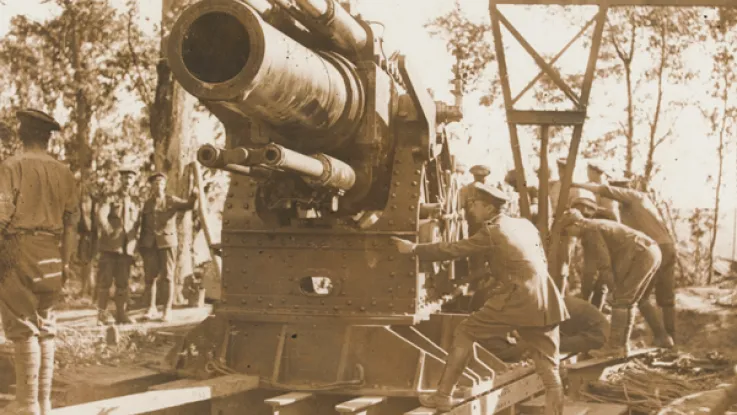

Apart from artillery exchanges, little fighting took place until 6 December when the Bulgarians attacked following a heavy bombardment. Fighting alongside the French, British units fought off several assaults on their positions.

‘A large mass of Bulgars was creeping up in the fog and were only about 50 yards away. We hastily formed up the men and fired five rounds rapid along the ground into the fog. Almost at the same time we heard B Coy [Company] on our left firing too. We must have got a lot of Bulgars as we could hear their shouts and groans. The Bulgar then charged and we gave them another 5 rounds rapid as they loomed up in the fog. Some of our fellows even got at them with the bayonet. The old Bulgar was so shaken up that he retired into the fog to pull himself together a bit.’Diary of Captain Noel Drury — 8 December 1915

The Birdcage

Outnumbered and lacking sufficient artillery, the Anglo-French forces fell back on Salonika. Luckily for them, the Germans prevented the Bulgarians from continuing their advance into Greece, as they still hoped to win the Greeks to their side.

Nevertheless, fearful of a Bulgarian assault on Salonika, and uncertain of neutral Greece, the Allies spent the first half of 1916 constructing a fortified line known as ‘The Birdcage’ in the hills around the city.

‘We have now started digging a new defensive line. It is very different work from Gallipoli. There we had to dig in anywhere we happened to be whether it was well sited or not, but here we can site our trenches and redoubts so as to give the best field of fire… The work on the trenches, MG [machine-gun] emplacements and redoubts goes on fast. We have done an enormous amount of revetting trenches with brush wood so that they won’t fall in… The wire entanglements are wonderful and I hear that we have used no less than 1,000 miles of wire per mile of front.’Diary of Captain Noel Drury — 8 January 1916

Multi-national force

The Bulgarians did not attack Salonika. And the Allies, once re-inforced, were able to advance north and west during 1916. They established a front line that ran from the Albanian coast through northern Greece to the Gulf of Orfano (also known as the Strymonian Gulf) on the Aegean Sea.

This ‘Army of the Orient’ was a multi-national force under French command. French, Serbian, Russian and Italian forces manned the western portions of the line and successfully captured Monastir in Serbia on 19 November 1916. British formations held the area east of the Vardar River, the trenches west of Lake Doiran, and patrolled the Struma Valley to the east.

Heat and disease

At its utmost, Lieutenant-General George Milne’s British Salonika Force (BSF) eventually numbered over 200,000 soldiers. These men faced a boiling summer climate and many succumbed to heatstroke. To counter this, travelling was usually undertaken at night.

British troops in the Struma Valley used cyclists and cavalry to patrol and fortify villages in order to deny them to the Bulgarians and Turks. Both sides evacuated the valley in the summer, owing to the prevalence of diseases like malaria, which alone caused 160,000 British casualties during the campaign.

‘Marching is very hot and tiring and we get a thirst which no amount of drinking will satisfy; our water bottles are very precious things. Our bottles are filled before moving off and no man must drink until the order is given, although we get a longing to empty the bottle in one glorious drink. The water men have difficulty in keeping up the supply, which has to be carried in leather bags on the mules. We go a long way up the Seres Road, one of the few decent roads in the country, then branch off… I begin to lose interest in life and when we lie down again would like to stay there and die, but there is some strange force which says “stick it” until you drop from sheer exhaustion… Through the endless night we put one foot in front of the other, aching in every joint’.Diary of Private George Veasey, 8th Battalion The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry — July 1916

Doiran

In April 1917 the British 22nd, 26th and 60th Divisions helped attack the defences around Doiran and on the Vardar as a diversion from the main Franco-Serb offensive to the west. They were repulsed and the main attack also failed.

The front line thereafter remained more or less static until September 1918 when the Allies, now including Greece, launched a new attack at Doiran.

Once again the British-Greek assault failed, with the attackers sustaining over 7,000 casualties, but the Serbs broke through in the mountains to the west. With no reserves and a starving population at home, the Bulgarians were forced into a general retreat, harried by the pursuing Allies. Bulgaria finally signed an armistice on 28 September 1918.

Criticism

The army in the Balkans was criticised at the time as a waste of men and material, with the troops there having an easy time. However, drained of strength and morale by the harsh conditions, the poorly supplied BSF managed to bring about a successful conclusion.

The campaign ended with the defeat of Bulgaria, liberation of Serbia and strategic exposure of Austria and Turkey. Despite these successes, the Balkan Front has become one of the forgotten 'side-shows' of the war.