Egypt

Britain’s strategic interest in Egypt increased after the construction of the Suez Canal. Opened in 1869, the Canal considerably shortened the trade and military routes to India and the East. In 1875, the British government bought shares in the Suez Canal Company.

Egypt, which owed nominal allegiance to the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul, had become virtually bankrupt by 1878. The dire economic situation led to Britain and France taking control of Egyptian finances and, in effect, running the country.

This caused outrage among large numbers of Egyptians. Their anger was exacerbated by the decision of their ruler, the Khedive (Viceroy), to get rid of many Egyptian Army officers as a money-saving measure. Many Egyptians also sought wider reforms that would increase opportunities for previously excluded groups.

Arabi Revolt

In May 1882, one Egyptian officer, Colonel Ahmed Arabi, sidelined the Khedive and led a revolt against what he and his supporters saw as unwarranted foreign interference in Egypt’s affairs. They also wanted to reform Egyptian society.

The British government concluded that in order to protect its strategic and financial interests in the region, military intervention was unavoidable.

After a naval bombardment of Alexandria in July, a British and Indian force of 35,000 men under Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet Wolseley sailed into the Suez Canal and landed at Ismailia the following month.

Map of Egypt, 1882

Kassassin

On 10 September 1882, Arabi led an Egyptian force against British troops at nearby Kassassin in an attempt to recapture the Suez Canal. The battle's outcome was in the balance until British reinforcements arrived and secured victory just as darkness began to fall.

Tel-el-Kebir

On 13 September, after a daring night march, Wolseley’s troops surprised the Egyptians at Tel-el-Kebir and drove them from their trenches.

When Wolseley entered Cairo the following day, Arabi and his army surrendered. The authority of the Khedive was restored, but the British remained in Egypt to ensure stable and co-operative government.

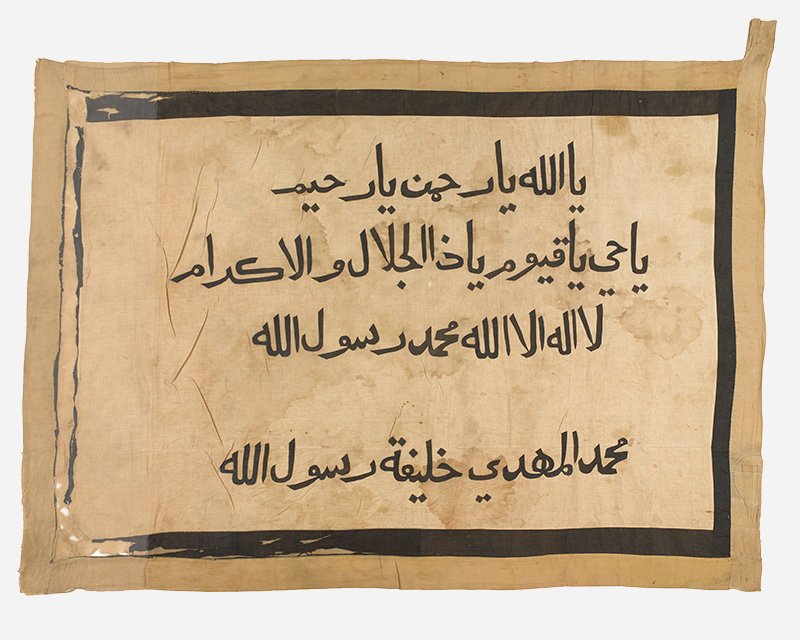

The Mahdi

In occupying Egypt, Britain also assumed responsibility for Sudan, which had been under Egyptian rule since the 1820s. An Islamic revolt had begun there in 1881, led by Mohammed Ahmed, who styled himself the ‘Mahdi’ or ‘guide’.

By the end of 1882, the Mahdists controlled much of Sudan. On 5 November 1883, at El Obeid, they annihilated an Egyptian force that had been sent to restore order.

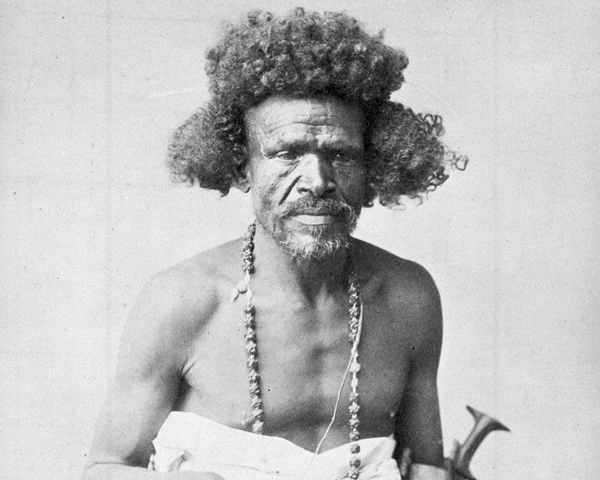

Osman Digna

The Mahdi was supported by Osman Digna, leader of the Hadendoa Beja people of eastern Sudan. In some British accounts from the period, the Beja are described as 'fuzzie-wuzzies' in reference to their hair.

In January 1884, Digna commanded a Mahdist army - mainly composed of his fellow Beja tribesmen - which wiped out an Egyptian force under Colonel Valentine Baker outside the Red Sea port of Suakim.

El Teb and Tamai

To rectify this situation, a 4,000-strong British-Indian force under Major-General Gerald Graham was sent out to Suakim. On 29 February 1884, it defeated Osman Digna at El Teb. But two weeks later, on 13 March, it was almost overwhelmed at Tamai.

The British fought in two brigade squares, one of which was temporarily broken by the Mahdists. The situation at Tamai was only retrieved when the second square moved up in support.

These two victories were a boost to public morale, but they had little long-term effect. Osman Digna was able to recover from his losses and Graham’s force was withdrawn, leaving only a small garrison at Suakim.

Map of the Sudan, 1884

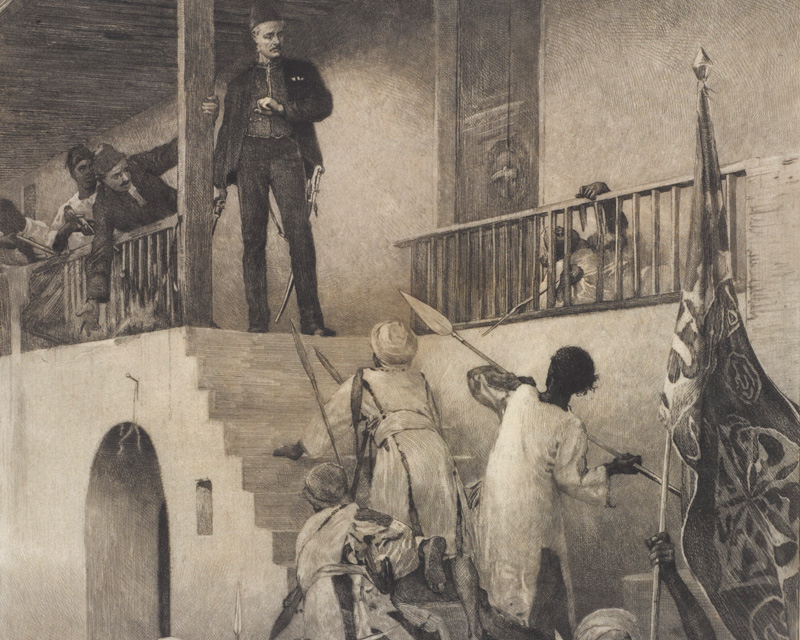

Gordon in Khartoum

Meanwhile, Major-General Charles Gordon had been sent to Sudan with orders to oversee the evacuation of Khartoum. Gordon was familiar with the region, having already governed there the previous decade. However, instead of focusing on evacuation efforts, he elected to stay and defend the city.

In May 1884, Khartoum was invested by the Mahdi. And Britain was forced to organise an expedition to rescue the besieged General Gordon.

Relief force

Wolseley’s relief column set off from Wadi Halfa in October 1884. Realising that his infantry, travelling in boats up the River Nile, might not reach Khartoum in time to save Gordon, he detached a desert column to travel overland by a faster, but more dangerous route.

This force, commanded by Brigadier-General Sir Herbert Stewart, was composed of four regiments of camel-mounted troops formed from the various units in Egypt and a detachment of the 19th Hussars.

Abu Klea

On 17 January 1885, the desert column was attacked by the Mahdists at Abu Klea. Despite suffering heavy losses to British rifle fire, the Mahdists succeeded in penetrating the British square, which was closed only after desperate hand-to-hand fighting. The British suffered 168 casualties, the Mahdists about 1,100.

The column finally reached Khartoum on 28 January 1885, two days after Gordon had been killed and the town had fallen.

‘The most savage and bloody action ever fought in the Sudan by British troops.’Winston Churchill on Abu Klea — 1899

Humiliation

For Britain, the death of General Gordon at Khartoum was a national humiliation. There was strong public pressure on the government to send another expedition to avenge him and restore Egyptian rule in Sudan.

A Mahdist invasion of Egypt was defeated during 1888-89. But it was not until 1896 that the government authorised military action. This decision may have been influenced by concerns that if Britain did not conquer Sudan, then the Italians and French would.

Re-conquest

In 1896, an Anglo-Egyptian army, led by Major-General Herbert Kitchener, entered Sudan. Kitchener understood the importance of keeping his force supplied, and he built a railway as he advanced and used steamers to move his troops and equipment down the River Nile. Progressing slowly but surely, he inflicted a number of defeats on the Mahdists.

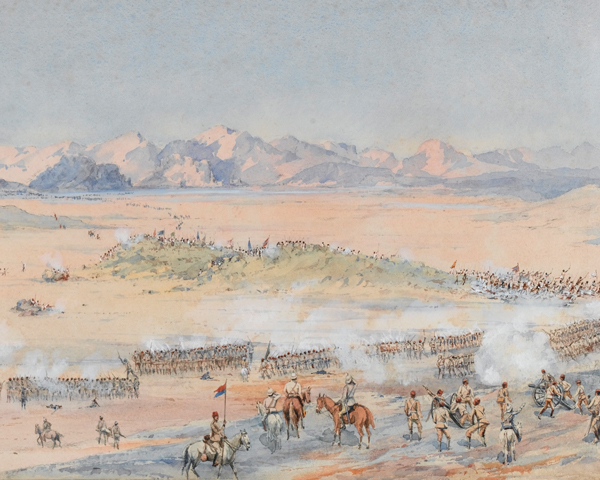

Atbara

On 8 April 1898, Kitchener’s force of about 12,000 attacked the fortified camp of a Mahdist army at Atbara. After a fierce struggle, the tribesmen were completely routed. The commander, Emir Mahmud, was captured along with 4,000 of his men.

Omdurman

Finally, on 2 September 1898, at Omdurman, Kitchener inflicted a crushing defeat on the forces of the Khalifa, Abdullah Ibn-Mohammed, who was the successor to the Mahdi.

Although they attacked with fanatical bravery, the Mahdists were no match for the rifles and Maxim machine guns of Kitchener’s army. By the end of the day, they had suffered approximately 27,000 casualties. The Anglo-Egyptians lost only 43 dead.

The Battle of Omdurman broke the power of the Mahdists. And although the Khalifa remained at large until November 1899, Sudan was quickly pacified.

‘With a crash the bullets leaped out of the British rifles… section volleys at 2,000 yards… [The Mahdists] could never get near and they refused to hold back . . . It was not a battle but an execution.’Description of Lee-Metford rifle fire at Omdurman by journalist George Steevens — 1898