Japan strikes

On 7 December 1941, the Japanese attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii and then declared war on Britain and the United States. The British colony of Hong Kong was attacked the next day. It surrendered on 25 December.

Japan also landed troops in the Philippines, on British territories in Malaya (now Malaysia) and northern Borneo, and on several Allied-held island staging posts in the Pacific Ocean.

Japanese forces had already occupied French Indo-China (now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) in 1940, and had been fighting in China since 1937.

Perimeter

In the first months of 1942, the Japanese launched further attacks against British Burma, the Australian-administered territories of New Guinea and Papua (both now part of Papua New Guinea), and the islands of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

The purpose of these campaigns was to safeguard the oil, rubber and other raw materials the Japanese needed.

They would also create a fortified perimeter around an economically self-sufficient Japan, which could then be defended until the Allies tired of war.

Malaya

On 8 December 1941, Japanese troops landed at Singora (Songkhla) and Pattani in Thailand, which immediately signed an armistice. Landings also occurred in Kota Bharu in northern Malaya. The invasion force from both landings quickly broke through British and Indian defensive positions, and then pushed down the west coast of Malaya.

The Japanese succeeded in making rapid advances through the jungle. By 25 January 1942, they had fought their way to Singapore, Britain’s major military base in Southeast Asia and the keystone of its regional defence system.

Defeat

Inadequate planning, little jungle training, poor intelligence, low morale, confused command structure and lack of air cover all contributed to defeat in Malaya. The British had also underestimated their battle-hardened enemy.

The Japanese were thoroughly prepared, determined and used the jungle effectively. Their infantry soldiers used bicycles to quickly advance, and they skilfully deployed tanks, which the British had thought impractical within the dense jungle. Their fast attacks never allowed the British forces time to re-group.

Singapore

The last British units crossed to the island of Singapore on 31 January 1942, destroyed its causeway and prepared for a siege. Unfortunately, the defences were primarily designed to repel a seaborne attack. The landward defences were much weaker.

Singapore's famed coastal guns were mostly equipped with armour-piercing shells, designed to penetrate the hulls of warships, but ineffective against infantry targets. More high-explosive shells would have caused larger enemy infantry losses.

The commander at Singapore, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, had no air cover and little artillery with which to stop the Japanese who attacked on 8 February.

Landings

Australian troops fought off initial landing attempts on the north-west of the island, while inflicting heavy casualties on the Japanese. However, the high command believed this to be a diversion from the main enemy assault and did not provide enough reinforcements or artillery support.

The outnumbered Australians eventually retreated amid the confusion of battle, allowing the Japanese to gain a foothold which they subsequently expanded following additional landings.

‘In some units the troops have not shown the fighting spirit expected of men of the British Empire… It will be a lasting disgrace if we are defeated by an army of clever gangsters many times inferior in numbers to our men.’Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival — 11 February 1942

Disaster

By 13 February, the British were trapped in a 28-mile (45km) perimeter around the city, with little hope of counter-attacking or even holding off the Japanese. Percival surrendered two days later, ending a disastrous campaign which lasted only 73 days. Around 9,000 British, Indian and Commonwealth soldiers were killed or wounded and 130,000 captured in Malaya and Singapore.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the fall of Singapore as ‘the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’.

Retreat from Burma

As a land invasion had long been thought unlikely, the defences of Burma (now Myanmar) had been neglected. When the Japanese attack began in January 1942, the British position there quickly deteriorated. By early March, the capital Rangoon (now Yangon) and its vital port had been lost.

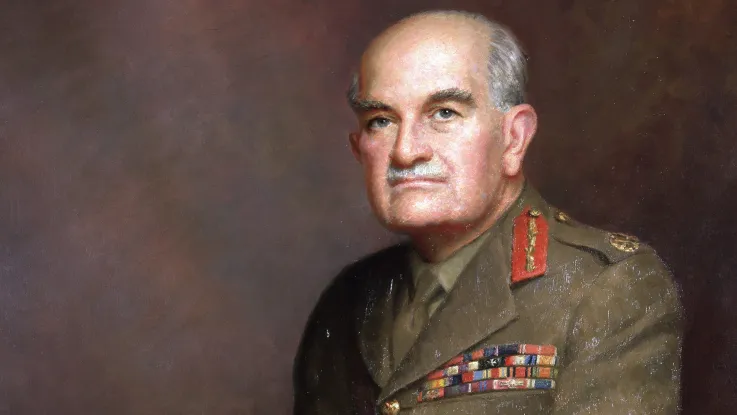

As the Japanese pushed northwards, the surviving British and Commonwealth troops under General Sir Harold Alexander, together with Chinese Army units, carried out a fighting retreat across nearly 1,000 miles (1,600km) of awful terrain. During the withdrawal to India, they lost most of their equipment and transport.

Although the first Burma campaign ended in defeat, the British could take comfort from the fact that their troops had reached India as fighting soldiers. They also had two of the best field commanders of the war in Alexander and General William Slim.

Arakan

Without adequate resources, a major counter-offensive into Burma was out of the question. Eastern Asia remained well down the list of British strategic priorities throughout 1942 and 1943.

But in order to wrest the initiative from the Japanese, General Sir Archibald Wavell, Commander-in-Chief in India, ordered the Eastern Army in India to attack the coastal Arakan region (now Rakhine State) in September 1942, and to capture enemy airfields on Akyab Island (now Sittwe).

Defeated again

After initial British success in Arakan, the Japanese counter-attacked. Their reinforcements crossed rivers and mountain ranges declared impassable by the Allies to hit their exposed flank and overrun several units.

The exhausted British were unable to hold. By March 1943, their position was untenable and the force was withdrawn.

Behind the lines

Wavell also sanctioned the 'Chindits', or Long Range Penetration Force. Their attacks behind the lines in Burma raised morale and proved that British soldiers could live and fight in the jungle. Their special forces operations also showed that troops could be supplied solely by air.

In February 1943 and March 1944, British and Indian Chindits sabotaged railways and roads, and encouraged local Burmese, Kachin and Keren resistance groups to attack the Japanese.

Diversion

The Chindits suffered heavy casualties and many succumbed to illness. But, by engaging enemy units and interrupting supply lines, they prevented the Japanese deploying all their resources to the main battle zones in Burma.

‘Word went round that there were snakes and before long five Kraits had been killed. The speckled Krait is a venomous snake about a foot long, which is chiefly dangerous because it is deaf and so easily trodden on. Defensive measures include boots and anklet puttees, shaking your clothes out and turning your boots upside down with care before putting them on, and examining your bed most carefully before retiring.’Captain Peter Gallup, Royal Artillery, 1945

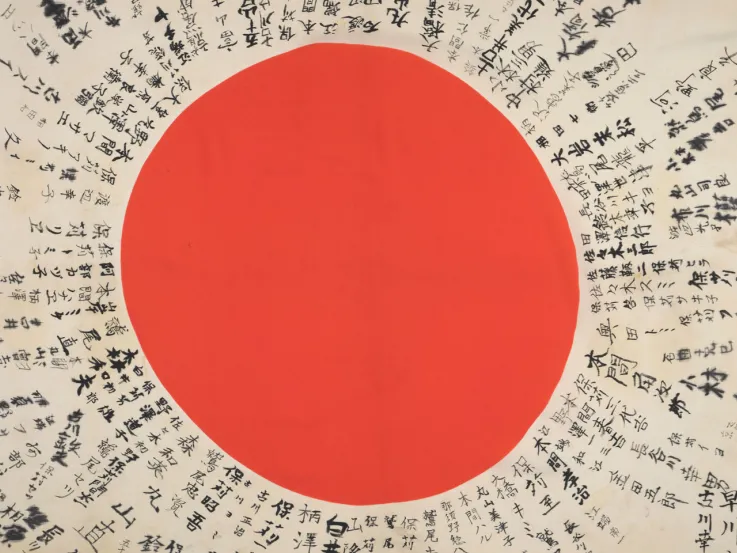

Prisoners

The Japanese despised the act of surrender. And, although they had signed the Geneva Convention, they had never ratified it. The lives of the thousands of British, Indian and Commonwealth soldiers that fell into Japanese hands were therefore extremely vulnerable.

Prisoners were held in appalling conditions both in established jails, like Changi on Singapore, and in makeshift jungle camps throughout Southeast Asia.

‘If you weren’t working hard enough they would make you stand and hold a stone above your head… You picked it up, which was better than collapsing because then they kicked you all over the place.’Gunner Jack Walker, a prisoner on the Thai-Burma railway

Forced labour

The Japanese treated prisoners badly because they saw surrender as dishonourable. They believed it was a soldier's duty to commit suicide if captured.

Many prisoners died through the brutality of their captors. But the punishing climate, and the lack of adequate food and medicine, meant that thousands more died from diseases such as cholera, dysentery and malaria.

Death Railway

The Japanese viewed prisoners as expendable labour for their war effort. Their most notorious project was the Burma-Thailand railway or 'Death Railway'. Opened in October 1943, it covered over 1,250 miles (2,000km) and cost the lives of over 15,000 prisoners of war and 80,000 local labourers.

South East Asia Command

In November 1943, a new phase of the war in eastern Asia began for the British with the formation of South East Asia Command (SEAC) under Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten.

SEAC replaced India Command in control of operations. Under its leadership, the prosecution of the war against the Japanese took on a new energy. More personnel, aircraft, equipment and supplies were also now available.

Stand firm

Previously, British troops had fallen back when the Japanese cut their lines of communication, and operations had practically ceased during the monsoon season.

Now, the policy was to stand firm and rely on air supply when cut off, and to fight on throughout the harshest conditions until relieved. The success of this policy was seen in 1944.

Imphal and Kohima

In March 1944, the Japanese 15th Army began an advance against India’s North-East Frontier to forestall a planned British invasion of Burma. The Japanese intended to capture the British supply bases on the Imphal Plain and cut the road linking Dimapur and Imphal at Kohima.

With Imphal in their hands, the Japanese would also be able to interrupt air supplies to China. It would also give them a base from which to conduct air attacks against India.

A Japanese diversionary attack in the Arakan was defeated in February (the Battle of the Admin Box), but in early April the troops at Kohima and Imphal were cut off.

Close quarters

Supplied by air, the garrisons threw back the Japanese attacks in bitter close-quarter fighting until relief forces reached them. At Kohima, a scratch force of 1,500 troops held a tight defensive perimeter centred on Garrison Hill. Facing them were 15,000 Japanese soldiers.

Between 5 and 18 April, Kohima saw some of the bitterest close-quarter fighting of the war. In one sector, only the width of the town's tennis court separated the two sides. When relief forces finally arrived, the defensive perimeter was reduced to a shell-shattered area only 350 metres square.

Relief

Despite the arrival of British reinforcements and supplies, the battle continued to rage around Kohima until 22 June, when the starving Japanese began a desperate withdrawal. The opening of the road at Kohima ensured the relief of Imphal.

The Japanese lost over 60,000 men and the momentum gained allowed General Slim’s Fourteenth Army to begin the reconquest of Burma.

‘The fighting all around its circumference was continuous, fierce, and often confused as each side manoeuvred to outwit and kill. There was always a Japanese thrust somewhere that had to be met and destroyed. Yet, the fighting did follow a pattern. The main encounters were on the spokes of the wheel, because it was only along these that guns, tanks, and vehicles could move.’Field Marshal William Slim recalling the Imphal fighting — 1956

British offensive

After their defensive victory, the British planned a new offensive to clear the last Japanese forces from northern Burma and drive them south towards Mandalay and Meiktila.

Fighting through the monsoon and supplied by air, troops of the Fourteenth Army now crossed the River Chindwin. XV Corps took Akyab in the Arakan following a series of amphibious landings in December 1944, while IV Corps and XXXIII Corps won bridgeheads across the River Irrawaddy in February 1945.

Victory in Burma

After fierce fighting, Meiktila and Mandalay were captured in March 1945. It was a decisive victory, won through the courage and endurance of the troops and the superb generalship of their commander William Slim.

The route south to Rangoon now lay open. And IV Corps was only 30 miles (48km) from the city when it fell to a combined air and seaborne operation in early May 1945.

Following their victory, the British began planning for new landings in Malaya and for the recapture of Singapore. But these were forestalled by the Japanese surrender in August 1945.

A Forgotten Army?

The Burma campaign was one of the longest fought by the British during the war. Remote from the experience of most people at home, and often sidelined in the contemporary press, it became known as the 'Forgotten War'; the troops serving there were the 'Forgotten Army'.

New Guinea

As the fighting in Burma raged, American and Australian forces were engaged against the Japanese in the territories of New Guinea and Papua. The Japanese had landed there in January 1942 and soon secured most of the north of the island.

They also took the nearby island of New Britain, where they established a major base at Rabaul. From there, they could direct operations in the South West Pacific.

By capturing both islands, along with the neighbouring Solomon Islands, the Japanese intended to use them for air attacks on northern Australia. Their seizure would also disrupt the sea and air links between the United States and Australia.

Japanese stopped

The Japanese drive to conquer all of the island of New Guinea ended with their failure to capture Port Moresby on the south coast. This was after their landing at Milne Bay was repulsed (August-September 1942) and a landward drive against the city was halted in desperate fighting on the mountainous Kokoda Trail (July-November 1942).

Counter-attack

Soon afterwards, in January 1943, the Americans and Australians won the Battle of Buna-Gona. This victory destroyed the main Japanese beachheads on the island of New Guinea and came after a gruelling battle of attrition.

This was followed by a string of amphibious assaults along the northern coast that eventually gave the Allies control of most of the island. Troops also landed on New Britain and, in tandem with air and naval attacks, helped isolate the powerful Japanese base at Rabaul.

Solomon Islands

To further neutralise Rabaul, the Allies also counter-attacked the Japanese in the neighbouring Solomon Islands. They made several landings, including Guadalcanal in August 1942, Vella Lavella in August 1943, and Bougainville in November 1943.

Securing New Guinea, New Britain and the Solomons helped pave the way for the Americans to return to the Philippines. They landed on Leyte in October 1944.

For the next ten months, US and Philippine forces steadily set about liberating the various Philippine islands until the Japanese capitulation in August 1945.

Borneo

The Allies also landed on the island of Borneo in a series of amphibious assaults between April and July 1945. Their aim was to secure its oil and establish the island as a launch pad for the liberation of the Dutch East Indies.

Pacific

Meanwhile, the Americans were undertaking an ‘island-hopping’ campaign against the Japanese over the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

While US air and naval forces engaged the Japanese fleet, marines seized strategically important islands that could be used as air and supply bases for their drive towards the Japanese main islands. Some of the fiercest fighting took place at Tarawa (1943), Saipan (1944), Guam (1944), Iwo Jima (1945) and Okinawa (1945).

Atomic bombs

After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 and the Soviet Union's formal declaration of war, Japan announced it would surrender on 15 August. This date was celebrated in many Allied countries as VJ Day (Victory over Japan).

The Allies believed that the atomic bomb attacks, which killed around 130,000 people, were necessary to achieve victory and avoid many more deaths. The intense fighting and heavy casualties sustained on outlying islands, like Iwo Jima and Okinawa, convinced them that the price of invading the Japanese mainland would be too high.

Following the surrender, Allied troops began occupying Japan from 28 August onwards. The Japanese Instrument of Surrender document was formally signed on 2 September 1945 on board the 'USS Missouri' in Tokyo Bay. This finally brought the Second World War to an end.