Burma

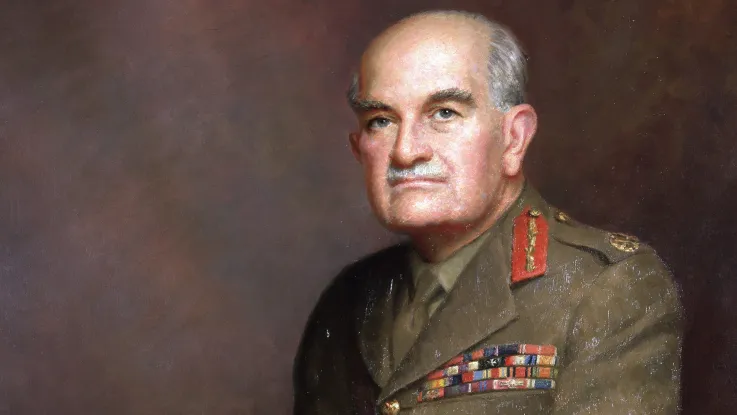

The Burma campaign (1942-45) was the longest fought by the British Army during the Second World War (1939-45). Most of the soldiers who served there were members of the Fourteenth Army under Lieutenant General William Slim.

This diverse force was the largest single Commonwealth army, comprising almost a million men by early 1945. Formed in 1943, it was made up of troops from India, Nepal, East and West Africa, and Britain.

Slim's army succeeded in defending British India before recapturing Burma (now Myanmar) from the Japanese.

Japanese occupation

The Japanese invasion of Burma had begun in January 1942 and, with its defences neglected, the country was quickly overrun. The Japanese occupation force was known as the Burma Area Army and consisted of the Fifteenth, Twenty-Eighth and Thirty-Third Armies.

Owing to Allied naval attacks on Japanese shipping, the Burma Area Army was not as well supplied as forces of a similar size elsewhere, particularly by 1944-45. Its troops often had to live off the land or try to capture Allied supplies.

Nevertheless, it was a formidable fighting force which included many veterans from Japanese conquests in China and elsewhere.

At close quarters

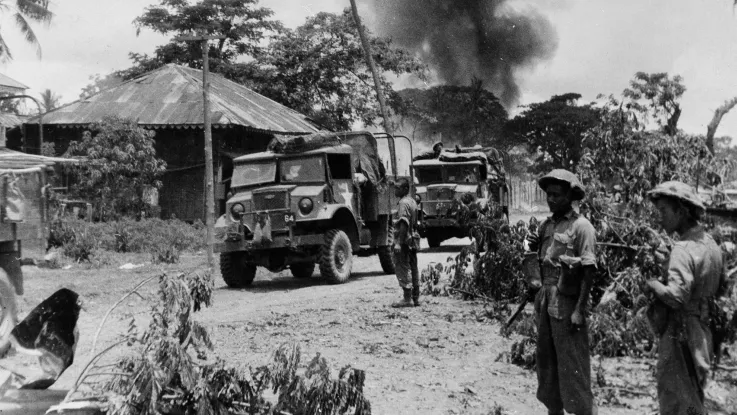

Much of the fighting in Burma took place in rough, malaria-ridden jungle terrain and scrubland. The wide open spaces of the North African or European theatres of the Second World War were comparatively rare.

As a result, close-quarter actions were a common feature of the campaign. British-Indian forces regularly encountered enemy patrols and attempted to capture entrenched Japanese positions.

The bitter fighting at Imphal-Kohima (March-July 1944) exemplified this type of close warfare. A decisive Japanese defeat in north-east India, this was the springboard for the Fourteenth Army’s subsequent re-conquest of Burma, which was largely complete by the early summer of 1945.

Map of India and Burma, 1944

Spoils of war

As they seized enemy positions during the course of these battles, the Fourteenth Army's soldiers began to acquire the personal belongings of Japanese soldiers. The items were often captured following close combat or when Japanese troops had been forced to hastily retreat from their dug-outs and entrenchments.

These souvenirs included swords of many varieties, but also 'senninbari' - one-thousand stitch belts made by Japanese women in order to bring good fortune to their loved ones - and, more frequently, 'yosegaki hinomaru', or good-luck flags.

Lucky charms

Upon signing up for wartime military service, or when deploying overseas, many Japanese soldiers were presented with these personalised flag mementoes by their families and friends.

Good-luck flags marked the beginning of a soldier’s military journey and were adorned with messages wishing them success in their endeavours. They were objects of real sentimental value to the soldier recipients, and served as emotive reminders of their loved ones and homes.

These flags stand in a long tradition of soldiers' lucky charms. Superstitious belief in the power of objects to bring luck or ward off danger has been prevalent throughout the ages and among soldiers of all nations.

‘Long-lasting fortune’

The good-luck flag shown here was captured in Burma in 1945. Dated 25 April 1942, it was presented to an officer called Tsuyoshi Ishihara, a squad commander from Hiroshima. The main message next to his name reads 'long-lasting fortune for warriors'.

Other messages from his wife, mother, niece and nephew include: 'invincible loyalty', 'victory', 'conquer London', 'determination', 'flourish in the south', 'wishing you health victory', 'brave outbound journey' and 'divine country'.

Japanese flag captured in Burma, c1942

Hinomaru

The design for all of these flags is the 'Hinomaru', which translates literally as 'the circle of the sun'. This was first adopted under the reign of Emperor Meiji in 1870 and continues to be used as the national flag of Japan today.

Flags presented early in the war were made of silk, often bought from a store and taken home for signing and personalisation. But as the war progressed, and resources like silk became scarce, cheaper cotton cloth was used.

Most flags were reinforced on all four corners with triangular tabs made from a variety of materials. These tabs were used to hoist the flags and sometimes to attach them to rifles.

Interpreting dates

Many flags don't have dates written on them. But they can sometimes be dated by the interpretation of the other messages. For example, any text mentioning fighting America or Britain can be dated to post-December 1941, after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong.

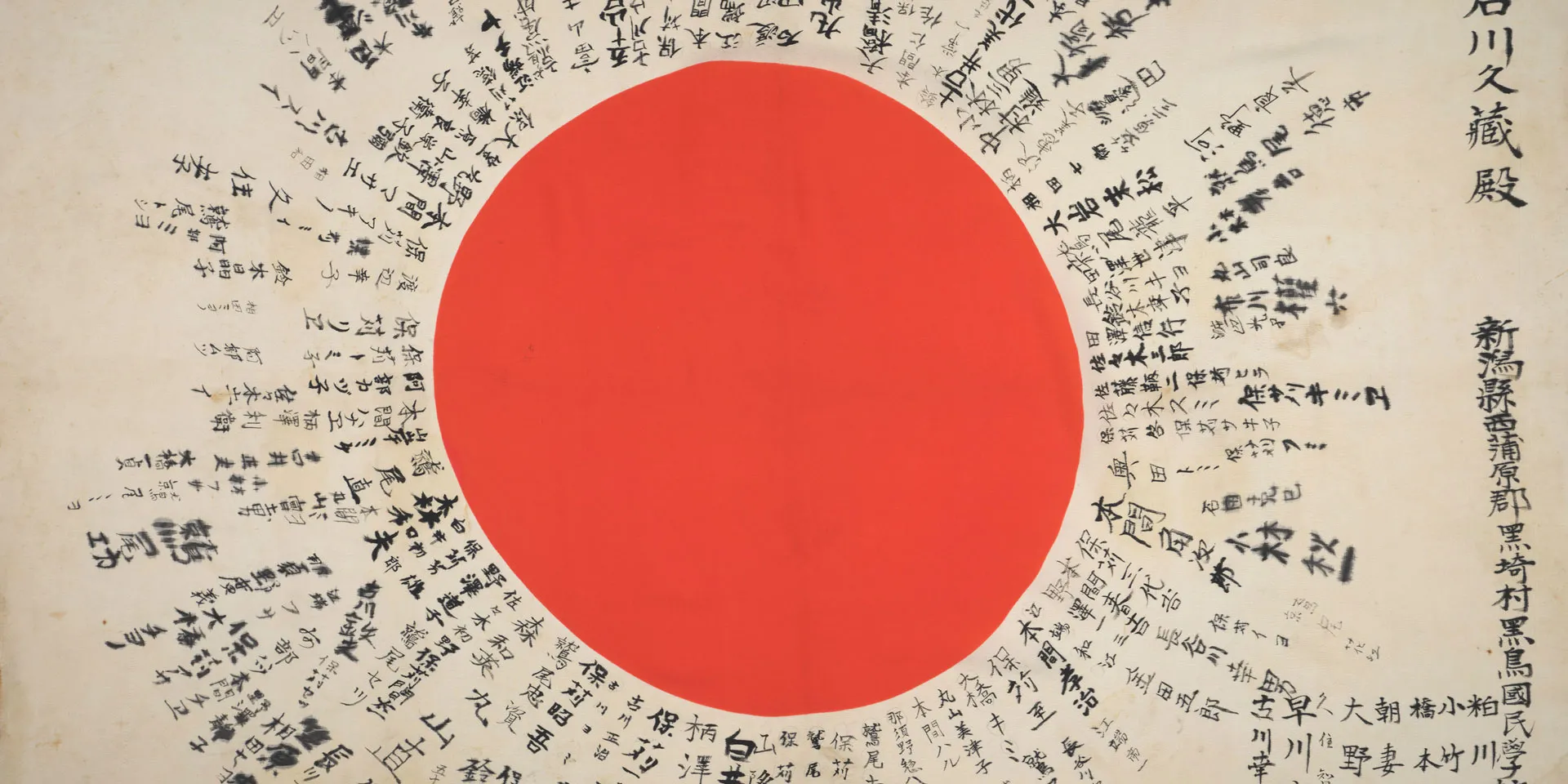

The flag above, captured in Burma by 6th Battalion, the 5th Mahratta Light Infantry, was presented to a soldier called Hisazo Ishikawa by Kurotori National School in Niigata Prefecture. We can date this flag to post-March 1941, as that's when the school was established.

Hope, victory and luck

A good-luck flag would usually contain the name of the recipient on the right-hand side. Names of friends and family members or the organisation that presented the flag often radiated from the centre.

Alongside this, there would be messages of hope, victory and good luck, as well as popular wartime patriotic slogans. These slogans were sometimes larger than the other characters.

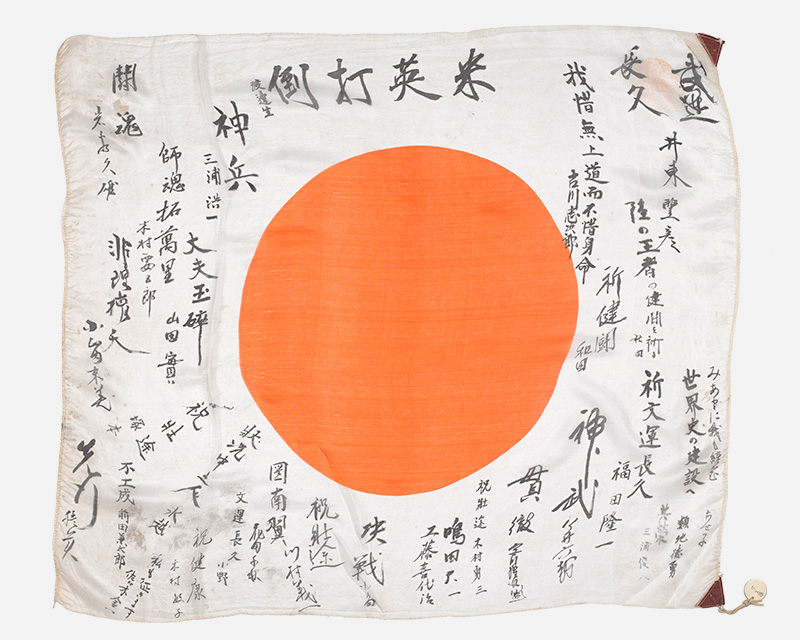

The messages in the example above, captured by 1st Battalion, the 1st Punjab Regiment, include: 'divine fighting spirit', 'leadership spirit will reach thousands of miles', 'beautiful death with honour and loyalty', 'huge accomplishments in distant lands', 'for construction of world history', and 'defeat the US and UK'.

Only half the story

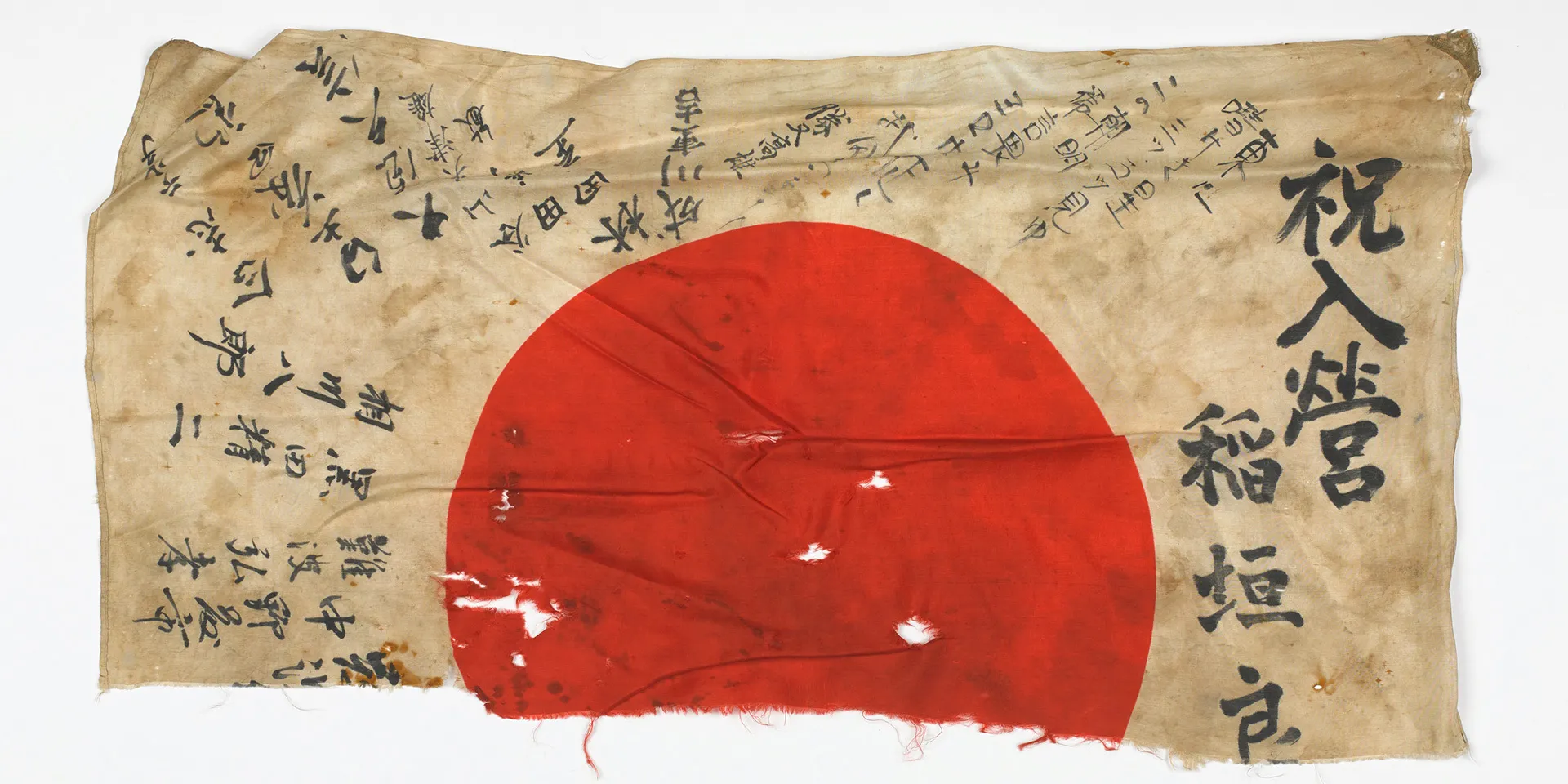

On 27 July 1944, 1st Battalion, The Seaforth Highlanders attacked enemy positions at Lokchao Bridge during XXXIII Corps' advance on Tamu. During the fighting, two Highlanders killed a Japanese soldier carrying the flag displayed above. As they could not decide which of them should keep it, they tore it in half and shared it.

A few days later, one of the men was killed. His portion of the flag was lost or perhaps recaptured. The remaining part was brought back to Britain and later donated to the National Army Museum.

The writing at the top-right of the flag reads: ‘Congratulations on your enlistment’. Only the surname of the original owner - Inagaki - remains visible.

A change of fortune

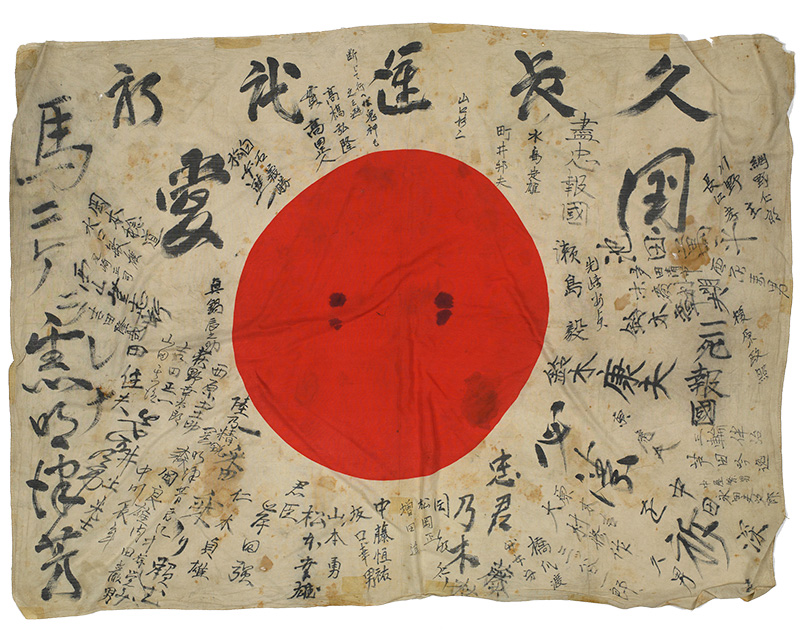

Personalised good-luck flags varied in size, but were usually small enough to be folded and worn on the person. Japanese soldiers often carried them in their uniform pockets or equipment packs. Sometimes, they were wrapped around the waist or kept under the shirt.

The bloodstained example shown above was captured on Ramree Island - just off the south coast of Burma - on 25 January 1945, when a platoon from 2nd Battalion, The Green Howards engaged around 40 Japanese soldiers. After the intense jungle firefight was over, one of the dead Japanese men was found to have this flag under his shirt.

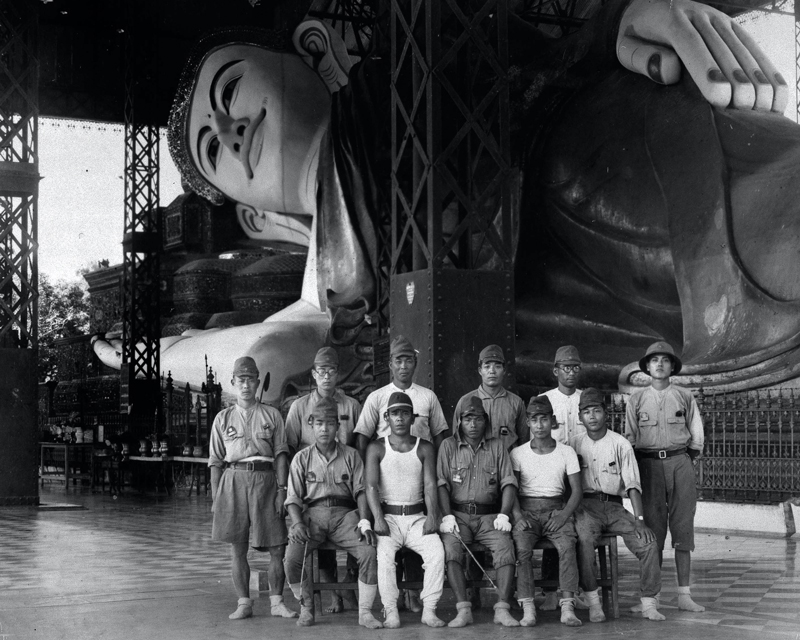

The flag was discovered along with many other personal effects, including photographs. One of these images (shown below) depicts a group of Japanese soldiers visiting the Shwethalyaung Buddha temple in Pegu (now Bago) in March 1943.

Surrender

This photograph represents a time when Japanese control of Burma was still secure and the wider war in eastern Asia was still going in their favour.

By 1945, the reverse was true. In Burma and elsewhere, Japanese forces were on the back foot. Their Burma Area Army had sustained thousands of casualties and suffered a series of defeats at the hands of the Fourteenth Army and its Chinese and American allies.

The surviving remnants of the Japanese Burma Area Army surrendered to the Allies at Moulmein (now Mawlamyine) on 15 August 1945.