The Ryshworth-Hill papers

In 2002, Mrs Valerie Wilkinson donated to the National Army Museum the papers of her late first husband, Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Ryshworth-Hill. Consisting of letters, diaries and photographs covering his service during and after the Second World War (1939-45), the collection also documents his courtship of Valerie, whom he met through mutual friends in the summer of 1942.

Letters between sweethearts during wartime are a regular find in the archives of military repositories such as the National Army Museum. However, the record descriptions tend to conceal the fact that quite often, as in the case of Valerie, the women in these relationships had an interesting story of their own to tell.

Valerie and Anthony

Valerie Erskine Howe (1920-2003), from Uckfield, Sussex, met Anthony in 1942 in Oxford, where he had been sent to attend a training course. Valerie was a cousin of one of Anthony’s friends, and their friendship soon developed into a romance, despite the fact that Valerie had recently come out of a broken engagement.

When Anthony suggested that Valerie might ‘learn about life’ before marrying, she promptly volunteered for the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). Anthony left for North Africa in the autumn of 1942. Valerie joined No 8 ATS Training Centre at Leicester in November of that year.

'Wives and Sweethearts' exhibition poster, 2011

Detail from 'Wives and Sweethearts' book cover

Valerie’s story

There are two sides to Valerie’s story. First, there is the love story, documented through the hundreds of letters between her and Anthony – a story which has already been explored by the National Army Museum in exhibitions and publications. The other side is the adventure she had during this courtship, while attached to a Transport Company of the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC).

In the past, the Museum has concentrated its cataloguing resources on providing access to the stories of servicemen, like Anthony, whose role in operations and theatres of war have been little covered elsewhere, necessarily skimming over the role of women such as Valerie. Recently, we have been able to delve deeper and discover that her experience amounted to more than this striking photograph of her on a motorcycle reveals on its own.

Adjusting to military life

Valerie was just 22 when she joined the ATS. She had no idea what the future might hold for her, and yet her letters demonstrate a maturity and positive outlook which are both refreshing and illuminating.

In over 450 letters, airgraphs, airmails, postcards and notes, Valerie describes in elegant and amusing detail her training and duties as an ambulance driver, despatch rider and staff car driver with 597 Command (M) Transport Company Royal Army Service Corps at Salisbury Plain and Winchester from 1943 to 1945.

Hidden among words of love and endearment is a picture of how one woman adjusted to military life, and found her passion in the maintenance of motor vehicles and driving motor cycles.

‘I’m being essentially Army-minded and working with fervish [sic] concentration to get into the Advanced Squad. I’m learning all about Carbarettas and Cooling Systems and driving the WD vehicles around and around.’Correspondence of Valerie Ryshworth-Hill — February 1943

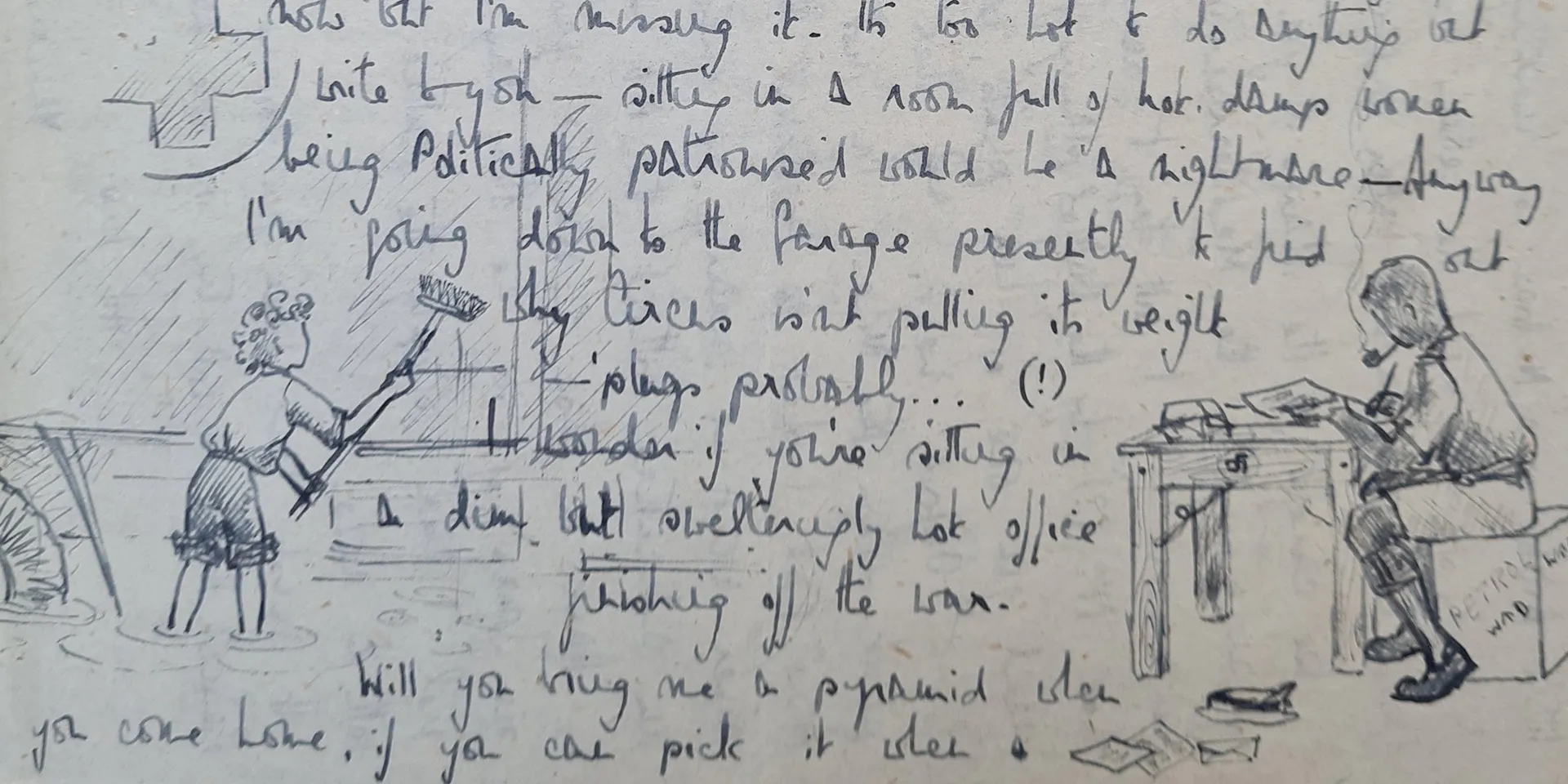

Detail from Valerie's letter featuring sketches of both herself (left) and Anthony (right)

Responsibilities

Valerie’s extensive correspondence includes details of her training, learning the mechanics of the vehicles for which she was responsible. The scene is set in vivid detail observing her sitting in a Nissen hut, her ambulance outside, waiting for a call, taking in the boredom, the lack of energy of those around her, and the dilapidated surroundings.

Her enjoyment of motorcycles and pride in the Bedford Ambulance, which she nicknames ‘One Hundred’, are evident in the letters to Anthony, as she attempts to portray to him the realities – and ridiculousness – of ATS life.

Also contained within her letters are the different personalities she meets as a staff car driver for The Hampshire Regiment, as well as her friendships with other ATS girls and the men of the RASC working alongside them. Littered throughout are pen sketches which add life to her descriptions and further illustrate her sense of fun.

‘These girls are all of them behaving, superficially, like men. With men’s responsibilities and men’s work and men’s clothes (we wear battle-dress, leather jackets and boots) it happens as a matter of course that some kind of a men’s mentality is evolved... The tension is comically balanced by the bathroom shelves being littered with powder-boxes and bottles and jars of this-and-that and scents and ribbons.’Correspondence of Valerie Ryshworth-Hill — May 1943

An officer’s wife

It is unclear whether Valerie's military service gave her a better idea of what life would be like as an officer’s wife. As Mrs Ryshworth-Hill, she initially continued in her role at the ATS, even after an early miscarriage in April 1945, although she was evidently weighing up her options and looking for opportunities to join Anthony in Europe.

Once officially released from the ATS in September 1945, she made plans to travel to Furstenfeld, Austria, where Anthony was based with the British occupation force. Within their correspondence, we next meet Valerie in 1946, by which time she was teaching English in Ankara, Turkey, where Anthony was in charge of the War Office Mountain Training School. It was another 13 years before they would settle together in England.

‘This morning the Invasion of Europe was begun. Tonight we are about to listen – and this the fantastic but gospel truth – we are in five minutes time to listen to Miss Constance Spry lecturing on How to Arrange Flowers – I am speechless.’Correspondence of Valerie Ryshworth-Hill — ‘D-Day’, 6 June 1944

‘An astonishing experience’

Reading Valerie’s letters today, we are left with a sense of how she immersed herself into a military environment which must have been totally new and bewildering for her. She pushed beyond the usual feminine stereotypes, enduring the unwanted attentions of her male passengers, and making the most of all the opportunities which came her way.

In 2002, a year before her death, Valerie donated her late husband’s papers, which had been stored in boxes in her garage for decades. She explained that Anthony’s suggestion to her in 1942 to join the Army and broaden her experiences had led her to ‘learn about life within a fortnight’ in what was ‘an astonishing experience altogether’.

She wondered if her letters ‘might have some bearing on Military History’. Twenty years later, it is clear that her story - and those of the other women who volunteered during the Second World War - is one to be shared.

Dig deeper

You can explore this collection (NAM. 2009-02-116), and many others like it, at the Templer Study Centre, the National Army Museum’s research facility in Chelsea.