ATS recruits parading with full kit, c1943

First recruits

The Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) was established in September 1938 as the threat of war loomed ever larger.

Recruitment was aimed at women between 18 and 43 years old. But the upper age limit was increased to 50 for ex-servicewomen, including veterans of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

The first recruits served as cooks, bakers, clerks and storekeepers. After initial training, they were asked to carry out trade tests to establish which area of work they should move into. Experience in civilian life was usually crucial. For example, if a woman had been a typist, she would be assigned clerical duties.

In the early days, new recruits were often surprised to discover that their accommodation was very basic or that they had little or no uniform.

‘We only had the absolute minimum of uniform. We were not allowed to cut anything to fit us, and there were only three sizes of everything: small, medium, and large. I was too big for the small, the medium was too long, and the large was far too big. So we could only turn things up, we couldn't cut or make anything to fit us.’Mary Coomer, ATS — 1938-45

ATS recruits being issued with uniform, 1942

Expansion

As more men were needed for combat roles, it was decided to increase the size of the ATS to take over other support tasks. Numbers reached 65,000 by September 1941.

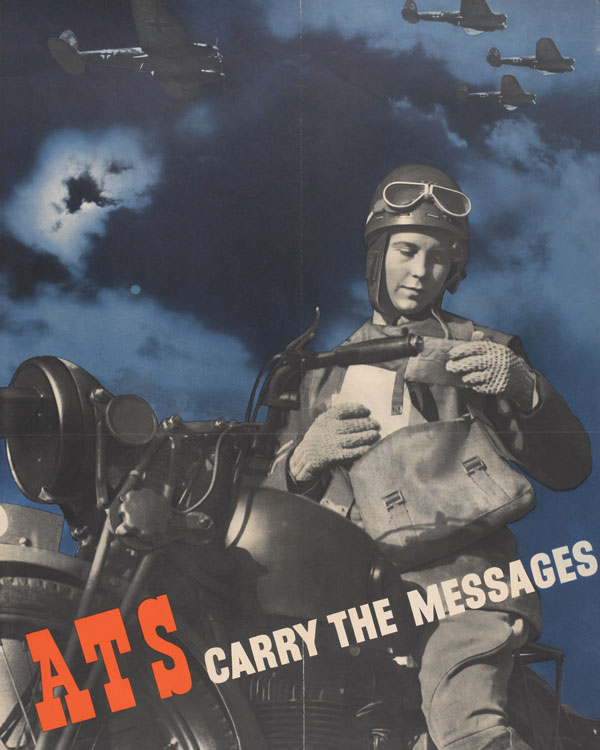

Women were not allowed to fight, but their range of duties expanded. They worked as telephonists, car mechanics, drivers, despatch riders, mess orderlies, postal workers, ammunition inspectors and military police.

ATS women training as firefighters, c1944

Conscription

Female conscription was introduced in December 1941. Women were given the choice of working in industry or farming, or of joining one of the military auxiliary services. The ATS was the largest of these, but women also joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force and the Women's Royal Naval Service.

Except for nurses, who joined Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, any women entering the Army joined the ATS.

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

The ATS also took on most women of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY). This provided the unit with ready-trained drivers.

Nominally, FANY continued as an independent unit to provide a cover for recruitment to the Special Operations Executive. Many female agents were parachuted into enemy territory.

Anti-aircraft Command

ATS personnel operated searchlights, range finders and sound detectors. They even aimed anti-aircraft guns, although Army rules meant that only men were allowed to fire them.

‘Until my experience in London I had been opposed to the use of women in uniform. But in Great Britain I had seen them perform so magnificently in various positions, including service with anti-aircraft batteries, that I had been converted. Towards the end of the war the more stubborn die-hards had been convinced and demanded them in increasing numbers.’General Dwight Eisenhower — 1948

Women from across the Empire

By June 1945, there were around 200,000 members of the ATS from all across the British Empire, including the Dominions, India and the West Indies. They served in many overseas theatres of operation as well as on the Home Front. Altogether, 335 ATS women were killed by enemy action and many more were injured.

Discrimination

Despite their vital contribution, ATS women were not treated the same as men. On average, they received two-thirds of the pay given to male soldiers of similar rank, and four-fifths of the rations.

ATS women were also subjected to many derogatory comments, even being referred to as ‘officers' groundsheets’ by some male soldiers.

Prejudice

Black women from the West Indies had to overcome the additional challenge of institutional prejudice. Initially rejected as recruits by the War Office on colour grounds, they later faced the dubious argument that they would find it difficult to adapt to the climate and culture of Britain, and would therefore be unable to discharge their duties effectively.

However, the growing demand for service personnel and pressure from the Colonial Office - eager to improve relations between Britain and the Caribbean - brought an end to this discriminatory recruitment policy. In 1943, the War Office agreed to recruit black West Indian women into the ATS.

A WRAC military policewoman on duty in Germany, c1970

Women’s Royal Army Corps

The ATS lasted beyond the Second World War, but was eventually disbanded in 1949. Its remaining troops were transferred to the newly formed Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC). This included all women serving in the Army, except for medical and veterinary orderlies, chaplains and nurses.

The available roles for women continued to expand. Eventually, they worked in over 40 trades, including as staff officers, clerks, chefs, dog handlers, communications operators, drivers, intelligence analysts, military police women, and postal and courier operators.

Ranks

At first, the WRAC inherited the ATS’s unique system of commissioned officer ranks. For example, a controller was equivalent to a colonel, and a second subaltern to a second lieutenant. However, in 1950, the unit adopted standard British Army ranks.

‘Most of the service women went into trade training. Drivers had to be over 5ft 5in and went to the Royal Corps of Transport. Policewomen over 5ft 8in went to the Royal Military Police. Some women went to the Royal Corps of Signals.’Angela Rose, who served in the WRAC 1978-80 — 2017

Disbandment

By 1991, many WRAC personnel were already serving with other regiments and corps. By the end of that year, they had been formally transferred.

The remainder of the unit was largely made up of pay clerks. When the WRAC disbanded in 1992, these became part of the Staff and Personnel Branch within the new Adjutant General’s Corps.

For some, the demise of the WRAC was a cause for regret. But it marked the beginning of women's full integration into the British Army. No longer restricted to a single, separate unit, their opportunities would continue to grow.

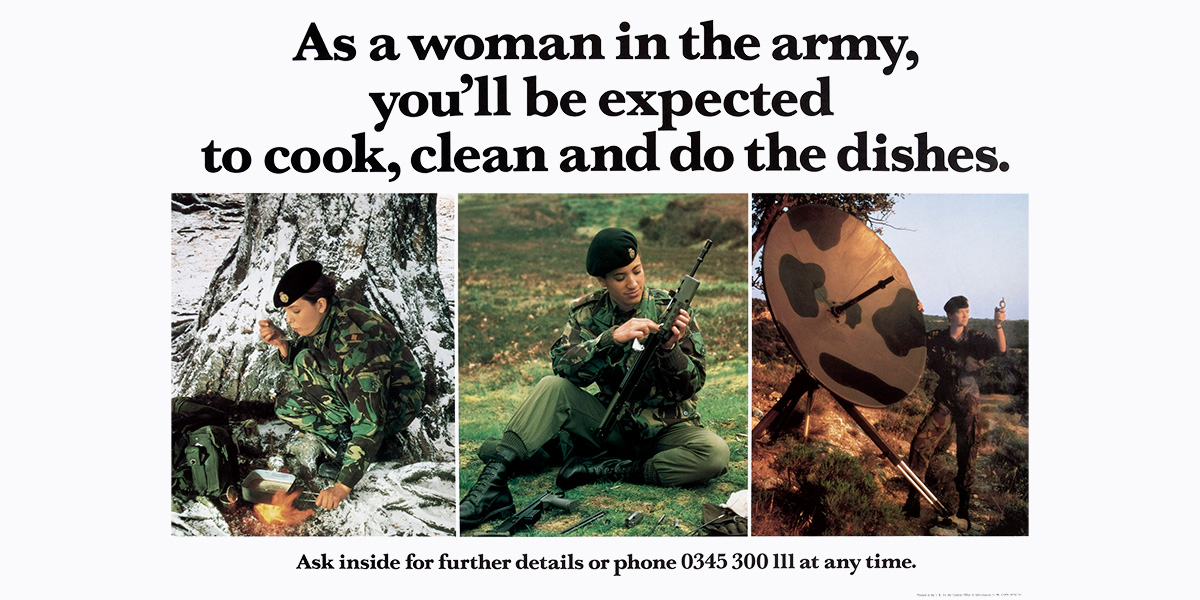

Women’s work?

In this video, discover how women’s contributions to the British Army have helped bring about change over the past 100 years. And see how Army recruiters have adapted their messaging accordingly.