Early career

John Moore (1761-1809) was commissioned into the 51st Regiment in 1776. He served in the American War of Independence (1775-83), before returning home and spending six years as a Whig member of parliament.

After serving in Corsica and the West Indies in the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802), he was promoted to major-general.

Ireland

Moore was then posted to Ireland, where he helped suppress the 1798 rebellion. His personal intervention was credited with turning the tide of battle at Foulksmills on 20 June. He also regained control of Wexford town before the notorious General Lake, thereby preventing its sacking.

Although the rebellion was put down with great brutality, Moore stood out from many other commanders in his refusal to carry out atrocities.

Egypt

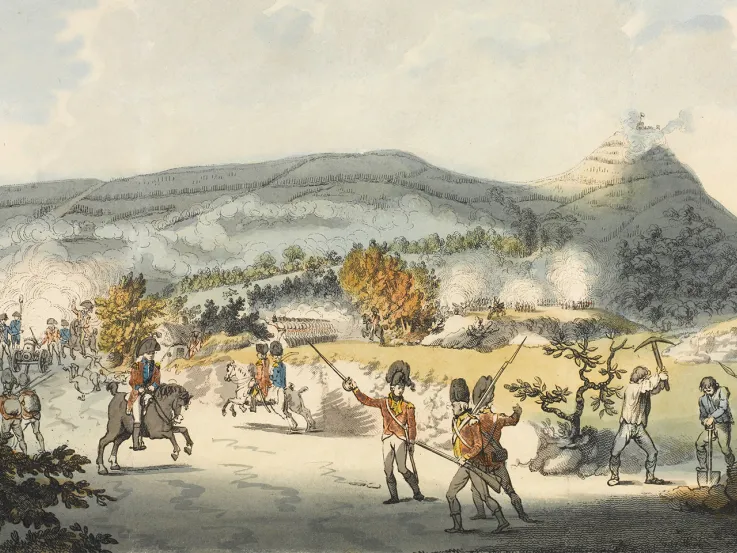

After commanding a brigade on the Dutch Expedition of 1799, during which he was wounded, service in Egypt followed. At the Battle of Alexandria on 21 March 1801, his reserve division bore the brunt of the French attack among the ruins of Nicopolis.

In the oil painting of the battle shown below, Moore is the mounted figure to the right of the colours rallying his men.

Home defence

Moore subsequently organised the defences of the English south coast against possible French invasion. It was on his initiative that the Martello Towers were constructed and a militia raised.

He also initiated the cutting of the Royal Military Canal in Kent and Sussex to defend a low-lying stretch of coast that was a possible French landing point.

Light infantry

It was during this period that Moore established a training camp at Shorncliffe in Kent. Here, light infantry tactics were taught to selected units including the 43rd, 52nd and 95th Rifles - the regiments that afterwards formed the famous Light Division.

Moore also made sure his troops were well housed and fed properly, earning himself a reputation as a comparatively humane commander. The barracks at Shorncliffe are now named after him.

In 1804, Moore was knighted and promoted to lieutenant-general.

‘His talents and firmness alone saved the British army [in Spain] from destruction; he was a brave soldier, an excellent officer, and a man of talent’.Napoleon Bonaparte on Sir John Moore

Peninsular War

In September 1808, following the removal of General Sir Harry Burrard for his signing of the Convention of Cintra, Moore was given command of the British Army in Portugal.

He advanced deep into Spain, planning to co-operate with Spanish forces against the French. But the surrender of Madrid and the arrival of Napoleon with an army of 200,000 soldiers forced him to retreat from Salamanca.

Retreat

Although the retreat was marked by foul weather, frequent skirmishing, long marches and widespread drunkeness, Moore was able to maintain the morale of his soldiers who were weakened by hunger and cold.

At one point, as ammunition ran low, he urged his men: ‘You've got your bayonets. Remember Egypt!’

‘Slowly and sadly we laid him down, From the field of his fame fresh and gory; We carved not a line, and we raised not a stone, But we left him alone with his glory.’Charles Wolfe, ‘The Burial of Sir John Moore at Corunna’ — 1816

Death

Moore withdrew northwards to the port of Corunna. There, he fought a skilful rearguard battle on 16 January 1809 that kept the French from attacking his embarking army.

At one point in the fighting, Moore led two regiments back into the village of Elvina, from where they had been ejected by the French. After firing a volley, they drove the French out at the point of the bayonet.

Moore was mortally wounded by cannon shot during this engagement, but lived long enough to learn that he had been victorious. His last words were: ‘I hope the people of England will be satisfied! I hope my country will do me justice!’

He was buried in the ramparts of the town. His French counterpart, Marshal Soult, was so impressed by Moore that he ordered a monument erected to his fallen foe as a sign of respect.