Anglo-Irish relations

Since the Middle Ages, English dominion over Ireland had been a cause of conflict between the two kingdoms. This ongoing friction took on new ethnic, religious and economic dimensions from the mid-16th century as successive English governments implemented a policy of colonisation (or plantation) to impose greater control over Ireland.

As part of this policy, waves of Protestant settlers from England, Scotland and Wales were given land confiscated from the predominantly Catholic native population. The largest of these plantations took place in the northern province of Ulster in the early 17th century after a failed uprising by local nobles resulted in their permanent exile.

Despite resistance, Catholic land ownership became increasingly marginalised. The Protestant ascendency in Ireland was further secured in 1691, when the forces of King William III defeated supporters of the deposed King James II at the Battle of the Boyne.

Political control

Throughout the following century, Ireland remained a separate kingdom with its own parliament in Dublin. However, in reality, it was firmly under British control. Executive power was held by a Lord Lieutenant appointed by the British government in Westminster, and the legislative freedom of the Irish parliament was severely restricted.

To maintain Protestant power, Catholics were denied many rights. They couldn't vote, hold political office, join the Army, or purchase and inherit land. Across Ireland, there was also a deep-seated resentment felt by the Catholic peasantry at the brutal exploitation they often experienced at the hands of their Protestant landlords.

Many civil rights were also denied to dissenting (i.e. non-Anglican) Protestant groups, such as Presbyterians, who felt similarly alienated as a result.

Powerful new ideas

These injustices led to a growing movement for political change. Reformers called not only for equality of rights, but also for greater independence from Britain.

Their ambitions were shaped and galvanised by the American War of Independence (1775-83) and the French Revolution (1789). These tumultuous events revealed how old regimes could be overthrown in the name of powerful new ideas of liberty, equality, democracy and nationhood.

Portrait of Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-98) (© National Gallery of Ireland)

Pamphlet written by Tone in August 1791 and reprinted by the newly formed Society of United Irishmen

United Irishmen

In October 1791, the Society of United Irishmen was founded by Theobald Wolfe Tone and a group of like-minded associates. With branches established in Belfast and Dublin, they set out to follow a path of peaceful reform towards a more independent and democratic Ireland.

While the majority of the leadership was Protestant, the group sought to transcend the sectarian strife of the past by uniting Irishmen of all denominations.

As the 18th century drew to a close, their calls for reform had met with some success. However, real power still lay with the British government and the Anglican Protestant elite. Resentment among Catholics and Dissenters continued to fester.

‘To unite Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter under the common name of Irishmen in order to break the connection with England, the never failing source of all our political evils, that was my aim.’Theobald Wolfe Tone, founder of the Society of United Irishmen

Revolution and War

The tension grew following the outbreak of war between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793. The bloody extremism of the French shook the British authorities. They feared that revolution could quickly spread across the English Channel and were determined to confront it with military force.

In a political atmosphere such as this, the path to peaceful reform in Ireland was blocked. As known sympathisers with the revolution, the United Irishmen were now viewed by the British as a serious threat.

When their collusion with the French government was exposed in 1794, the organisation was banned. A crackdown on its membership was instigated that drove Wolfe Tone into exile in America.

Militia and Fencibles

To bolster their strength against both internal enemies and the threat of invasion by France, the Irish government began recreating the local defence force known as the Militia.

This was a difficult and dangerous move. Not only was compulsory military service resented and resisted by many, but it also meant that the government had to take the risk of arming large numbers of Catholics, whom they did not entirely trust.

Their fears were compounded by the lack of regular troops in Ireland. Skilled soldiers were needed elsewhere in the war with France, and were replaced only with low-grade home service forces known as Fencibles.

Radicalisation

Driven underground, the United Irishmen became radicalised. They now sought to break all ties with Britain in order to create a wholly independent Irish republic and embraced violence as a means to achieve this.

To build their military capability, they formed an alliance with a militant underground Catholic group called the Defenders. This greatly expanded the number of men available for armed insurrection and gave them a wider national reach.

However, this alliance would severely undermine the objective of leaving behind the religious violence of the past. The Defenders were avowedly sectarian in their outlook, targeting Protestant landlords and militant groups like the Peep o’ Day Boys and the newly formed Orange Order.

French expedition

Also central to the United Irishmen’s strategy was an alliance with the French in the hope of gaining military support for an uprising.

In December 1796, their plan came within an ace of success when the French launched an expedition to land troops in Ireland. This had been negotiated by Wolfe Tone, who had returned from exile in America and now accompanied a French fleet bearing 14,000 men.

The fleet succeeded in eluding the Royal Navy and was only denied by violent winter storms. Some of their ships were lost off the southwest coast of Ireland; the rest were forced to return to France.

Counter-insurgency

This narrow escape from invasion raised the level of tension in Ireland to fever pitch. The government instigated a campaign of counter-insurgency, which in its severity amounted to a reign of terror.

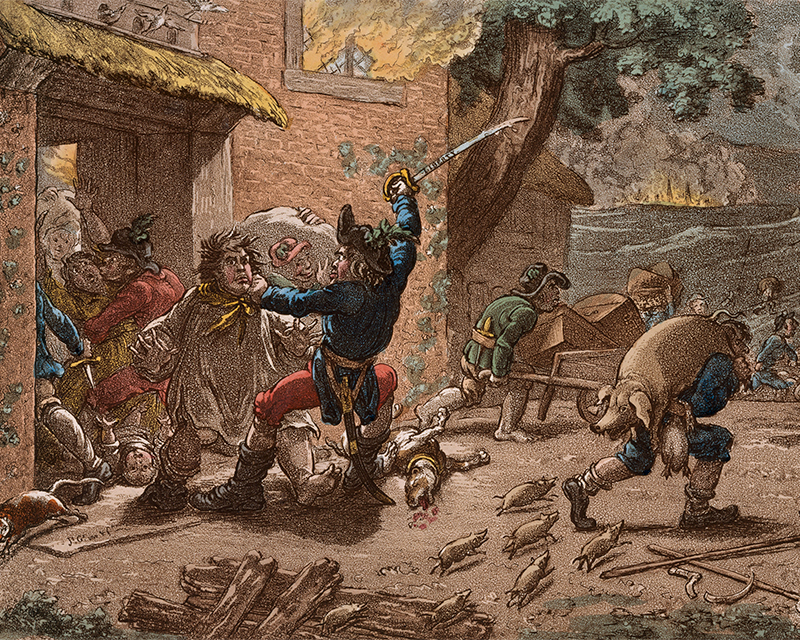

To break and cow its internal enemies, the government used ruthless methods of torture, summary execution, mass arrests and house burning. The Army and the Militia were supported in this work by the newly raised Yeomanry. This was composed overwhelmingly of loyalist Protestants and so served to further deepen sectarian divisions.

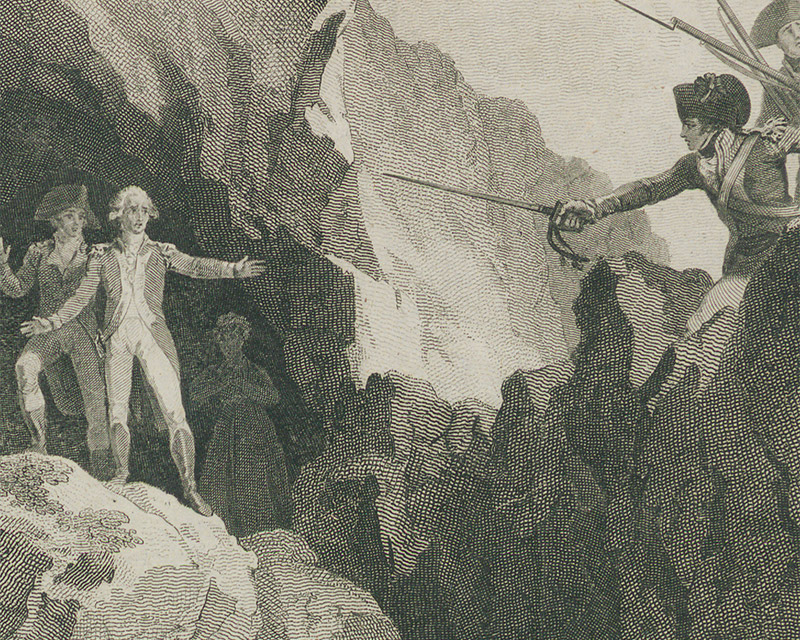

The government also established a network of spies which succeeded in penetrating and subverting the United Irishmen. This campaign resulted in the arrest and death of much of its leadership. Most notable among them was Lord Edward Fitzgerald, the rebels' figurehead and foremost military leader, who was fatally wounded while resisting arrest on 18 May 1798.

Outbreak

In the face of these growing threats, the United Irishmen felt compelled to launch their rebellion before it was too late. It began on the night of 23 May, signalled by the halting of mail coaches leaving Dublin.

However, the organisation had already been irretrievably damaged. Lack of leadership saw the uprising quickly descend into a series of isolated and uncoordinated outbreaks in the counties surrounding Dublin.

Poorly armed, trained and led, the rebels had little or no hope against the government’s forces. Dublin was placed under a strict military lockdown and was never seriously threatened.

‘Never did I see people under any military discipline in such a ragged situation, the generality of them was without shoes or stockings and scarce any clothing. They seem to be a mob of very desperate people and I am creditably informed their commanders, before they were ordered to attack any place, made them intoxicated with spirits.’Corporal Samuel Blomeley, The Coldstream Guards, describing the wretched condition of the Irish rebels — July 1798

Wexford

It was only in County Wexford that the rebellion managed to gain momentum. Incensed by stories of government brutality, and invigorated by a victory over the hated North Cork Militia at Oulart on 27 May, the rebels succeeded in capturing Enniscorthy and Wexford town. However, they could not capitalise on this success and were bloodily checked in their attempts to break out and capture the towns of New Ross, Arklow and Newtonbarry (now Bunclody).

Frustrated and embittered, the rebels perpetrated many atrocities against their enemies. Most cruelly, more than 100 loyalists were burned to death in a barn at Scullabogue. But such actions could not turn the tide of events. Demoralised, the rebels were compelled to fall back to their camp at Vinegar Hill, near Enniscorthy, where they attempted to regroup.

Ulster

Meanwhile, the rebellion had spread north to Ulster. In early June, the United Irishmen of Counties Antrim and Down, led by Henry Joy McCracken and Henry Munro respectively, rose in support of their southern comrades.

But, once again, the rebels lacked the military strength to make much headway. They were swiftly and brutally put down by British forces under Major-General George Nugent. Both McCracken and Munro were captured and executed.

Vinegar Hill

The authorities now turned their attention to the main rebel camp at Vinegar Hill. On 21 June, British forces under General Gerard Lake surrounded the site, subjecting it to a fierce artillery bombardment before storming the summit. The rebels suffered severe losses and were soundly defeated. While many managed to escape into the surrounding hills, it was clear that the rebellion was now over.

Again, in the desperation of defeat, the rebels resorted to atrocity, murdering 70 Protestant prisoners at the bridge in Wexford town. In retribution, the victorious loyalist army unleashed an orgy of violence upon the defeated rebels. This appalled Lord Cornwallis, the newly installed Lord Lieutenant, who harboured hopes of reconciling the warring factions and bringing an end to the conflict.

‘Murder appears to be their favourite pass time [sic].’Charles, Marquess Cornwallis, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, describing loyalist forces — 1798

Castlebar and Ballinamuck

Despite the crushing defeat at Vinegar Hill, the rebellion flared once more in August, this time in the west. General Jean Humbert succeed in landing a second, though much smaller, French force at Killala Bay in County Mayo. With only around 1,100 men, the French commander was heavily reliant on the local people rising en masse in his support.

There was a moment of hope for the rebels when Humbert's troops won a notable victory at Castlebar on 27 August. But this failed to spark a mass revolt. His small force was compelled to surrender to the British at Ballinamuck on 8 September, bringing the rebellion to end.

Wolfe Tone, who had accompanied a small group of French reinforcements, was captured at sea a month later. He was condemned to death by hanging, but instead cut his own throat and died in prison before his sentence could be carried out.

Failure

The rebellion was a total failure for the United Irishmen. Their forces had been vanquished and brutal reprisals had been meted out to both the rebels and the civilian Catholic population. Most of the rebel leadership had been killed and estimates of the total death toll have been put in the tens of thousands.

The United Irishmen's hopes of overcoming the sectarian hatred of the past had been dashed. Instead, this had only been deepened by the atrocities perpetrated by both sides.

Not only had the United Irishmen failed to attain any of their political objectives, but Ireland was brought under even closer British control. The Irish parliament was abolished and the country became a formal part of the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801.

For loyalists, the events of 1798 would serve as a warning of what could occur should British control ever weaken in the future.

The United Irish Patriots of 1798 (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

Legacy

Despite all of this, the rebellion still marked a significant turning point in Irish history, inspiring nationalists and radicals of varying opinions.

The liberal ideas of democracy, civil rights and republicanism were evident in other reform campaigns, including the Irish anti-slavery movement and the Irish National Land League. Rebel leaders like Wolfe Tone were also celebrated in Irish culture, serving as examples for future reformers to emulate.

While open conflict had failed, the rising saw the development of secret organisations pioneering tactics of violent insurgency, which would be honed by future Irish revolutionary groups like the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

At the same time, the violence of 1798 convinced some Irish nationalists to pursue peaceful methods, a process that culminated in the Home Rule campaign of the late 19th century.

All these factors would contribute towards the events which eventually brought independence to Ireland in 1921.