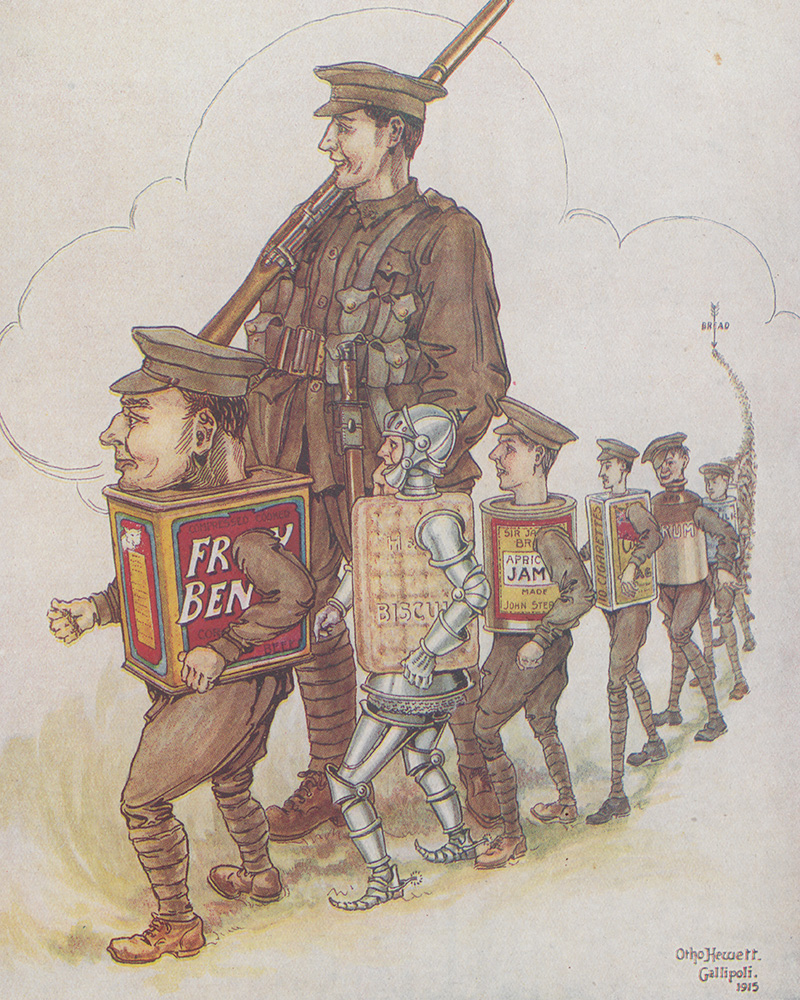

Rum rations

Stoneware jars were produced in vast numbers during the First World War (1914-18) and were used to store and transport a variety of liquids. Some carried whale oil, which helped protect troops from trench foot; others carried lime juice to keep scurvy at bay. But they were perhaps best known for carrying rum.

As in earlier conflicts, British and Commonwealth soldiers were entitled to a rum ration in the trenches. This was to be drunk in the presence of an officer or non-commissioned officer to guard against overindulgence. The daily allowance was 2.5 fluid ounces (about 70ml).

Each jar had the letters 'SRD' impressed on it, signifying that it came from the Supply Reserve Depot. Soldiers had their own ideas about what these initials stood for, including ‘Seldom Reaches Destination’, ‘Service Rum Diluted’ and ‘Soon Runs Dry’.

‘They have … stopped the men’s rum ration … because a blithering lot of fools made complaints about the amount of rum being sent out to English troops. I don’t believe half of the men could have existed without it all through the winter, and even now it’s awfully cold standing too [sic] at daybreak.’Lieutenant Maurice Asprey, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment), in a letter to his mother — 26 April 1915

Diagnosing dirt

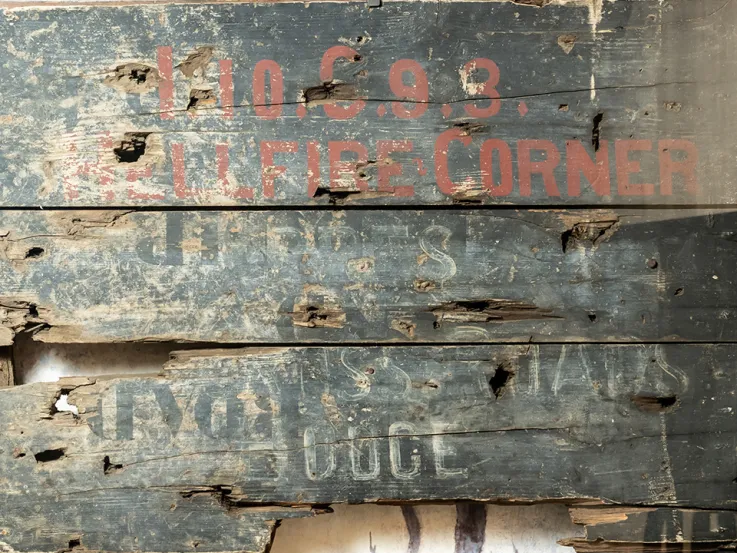

The rum jar now on display in our Conflict in Europe gallery was excavated in 1982 from the site of a trench occupied by British troops at Messines Ridge. Unsurprisingly, it emerged from the ground caked in mud.

An ethical question we often have to ask in conservation is whether dirt is historic or new. With a blood-stained tunic, for example, the blood tends to be classed as historic dirt, meaning it would be wrong to remove it. In contrast, dust that has settled on an object while held in storage would be considered new dirt.

It's quite possible that the mud bound itself to our rum jar over the many decades it lay buried in the ground. However, when making heritage decisions, we also have to take into account the historical context.

Mud is something that immediately springs to mind when contemplating the trench experience that First World War soldiers had to live through. While it's conceivable that the men took special care of their prized rum, it's easy to imagine the jar being kept in fairly mucky conditions.

In either case, we can be satisfied that the dirt attached to our jar is the same soil in which these soldiers were fighting more than 100 years ago.

Treating the jar with Paraloid B72

Installing the jar in the Conflict in Europe gallery

Careful consolidation

Prior to treatment, the mud was actively flaking from the jar, so we decided to consolidate it with an adhesive, Paraloid B72. First, we tested how the object would respond to the adhesive and its solvent, acetone. The two recorded effects were the slight darkening of the dirt as well as the desired effect of the dirt hardening. The ceramic itself experienced no change.

We started off by using a pipette to apply the adhesive to thicker sections of dirt. This allowed the adhesive to be absorbed, creating better internal stability. We followed this up by applying multiple layers to the entire jar with a spray gun. This effectively created a coat across the entire object that holds the dirt to the ceramic surface.

Once this process was complete, we were able to transport and install the jar in its new showcase without losing any of the mud. We can now be confident that it will remain stable during its time on display.

See it on display

Conserving the dirt on this jar gives visitors a rare insight into the conditions in which soldiers of the First World War fought, lived and drank!

Come and see it on display in our Conflict in Europe gallery, alongside other items that help shed light on life in the trenches.