Background

Weapons played a large part in creating the difficult and unusual circumstances of trench warfare which the British Army encountered during the First World War (1914-18). The destructive power of modern artillery and machine guns forced soldiers to seek cover on the battlefield and dig in for protection.

The First Battle of Ypres (20 October - 22 November 1914) marked the end of open and mobile warfare on the Western Front. Both sides dug in and a line of trenches soon ran from the Channel to the Swiss frontier.

These early trenches were built quickly and tended to be simple affairs that offered little protection from the elements. But they soon grew more substantial.

The front-line trenches were backed-up by second and third lines: 'support' and 'reserve' trenches. Communication trenches linked them all together. This system was strengthened with fortifications, underground shelters and thick belts of barbed wire.

For commanders, the greatest tactical problem was to get troops safely across the fire-swept divide between the trenches to penetrate enemy defences. While modern weapons had helped create this problem, generals hoped that they would also assist the Army in fighting their way out of it.

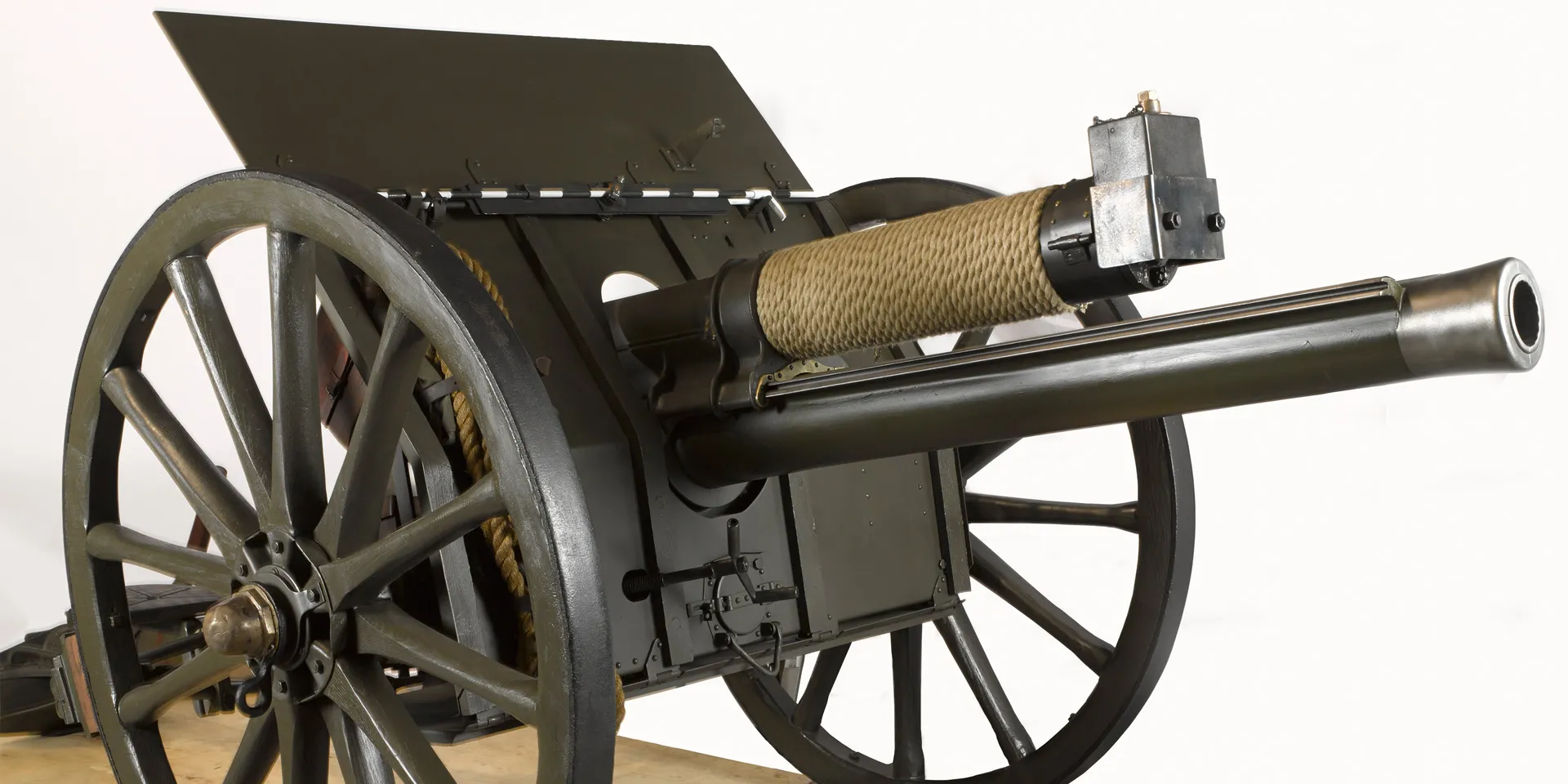

Artillery

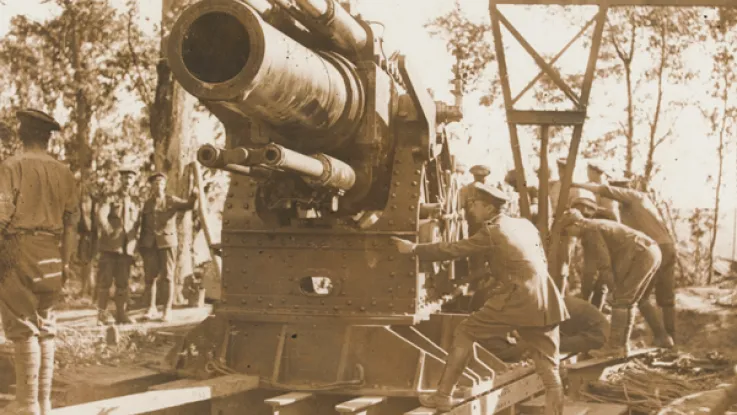

Artillery was the most destructive weapon on the Western Front. Guns could rain down high-explosive shells, shrapnel and poison gas on the enemy. Heavy fire could destroy troop concentrations, wire and fortified positions.

Artillery was often the key to successful operations. At the start of the war, the British bombarded the enemy before sending infantry over the top, but this tactic became less effective as the war progressed.

Before the Battle of the Somme (1916), the Germans retreated into their concrete dugouts during the artillery barrage, emerging when they heard the guns stop.

Later in the war, the British used artillery in a defensive way, rather than attempting to obliterate enemy positions.

The army developed tactics like the creeping barrage, which saw troops advance across no-man's land behind the safety of a line of shell fire. They also made the most of new technologies like aircraft, sound ranging and flash spotting to locate and neutralise enemy artillery.

‘We are going to beat the Germans by heavy howitzers and heavy trench mortars as they are the only weapons which will smash him in his deep dug outs.’Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, at the start of the Battle of the Somme — 3 July 1916

Machine guns

The machine gun was one of the deadliest weapons of the Western Front, causing thousands of casualties. It was a relatively new weapon at the start of the war, but British and German forces soon realised its potential as a killing machine, especially when fired from a fixed defensive position.

The Vickers machine gun (above) was famed for its reliability. It could fire over 600 rounds per minute and had a range of 4,500 yards.

With proper handling, it could sustain a rate of fire for hours. This was providing that a necessary supply of belted ammunition, spare barrels and cooling water was available. When there was no water to hand, soldiers would urinate in the water jacket to keep the gun cool!

The Lewis Gun (above) was the British Army’s most widely used machine gun. It required a team of two gunners to operate it, one to fire and one to carry ammunition and reload.

As gunnery practice improved, the British were able to use this light machine gun to give effective mobile support to their ground troops. The gun was so successful that it was later fitted to aircraft.

‘The noise of the German machine guns was completely inaudible and, as I watched, the ranks of the Highlanders were thinned out and torn apart by an inaudible death that seemed to strike them from nowhere. It was peculiarly horrible to watch.’Lieutenant Richard Barrett Talbot Kelly observing machine gun fire at the Battle of Arras — April 1917

Aircraft

Aircraft were such a new technology during the First World War that no one recognised their potential as a weapon at first. Pilots would even wave at enemy planes when they passed each other on aerial reconnaissance duties.

Initially, aircraft carried out artillery spotting and photographic reconnaissance. This work gradually led pilots into aerial battles against enemies engaged in similar activities.

As the war progressed, aircraft were fitted with machine guns and strafed enemy trenches and troop concentrations. As the speed and flying capabilities of aircraft improved, they started bombing airfields, transportation networks and industrial facilities.

Mortars

Mortars of all sizes were used on the Western Front. Their size and mobility offered advantages over conventional artillery as they could be fired from within the safety of a trench. They were also effective at taking out enemy machine-gun and sniper posts.

The Stokes mortar (above) was the most successful British mortar. It consisted of a metal tube fixed to an anti-recoil plate. When a bomb was dropped into the tube, it would hit a firing pin at the bottom and be launched. It could fire 20 bombs per minute and had a range of 1,100 metres.

Mines

Tunnelling and mining operations were common on the Western Front. Tunnels would be dug under no-man’s land to lay explosive mines beneath enemy positions. Much of this work was done by special Royal Engineers units formed of Welsh and Durham miners.

Minutes before they attacked on the Somme on 1 July 1916, the British exploded several huge mines packed with explosives under the German position. Although many defenders were killed by the explosions, the delay in starting the advance meant that the Germans had time to scramble out of their dugouts, man their trenches and open a devastating machine-gun fire.

The British deployed mines more effectively at Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917. A series of huge explosions killed around 10,000 Germans and totally disrupted their lines.

Following the detonation of the mines, nine Allied infantry divisions attacked under a creeping artillery barrage, supported by tanks. The devastating effect of the mines helped the men gain their initial objectives. They were also helped by the German reserves being positioned too far back to intervene.

Rifles

Rifles were by far the most commonly used weapon of the war. The standard British rifle was the Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE) Rifle Mk III. It had a maximum range of 2,280 metres, but an effective killing range of 550 metres.

A well-trained infantryman could fire 15 rounds a minute. In August 1914, the Germans mistook the speed and precision of the British rifle fire for machine guns.

The SMLE was usually fitted with a bayonet, which afforded a one-metre reach in hand-to-hand combat.

A rifle fitted with a bayonet could prove unwieldy in a confined trench, so many soldiers preferred to use improvised trench clubs instead. However, the bayonet remained a versatile tool that was also used for cooking and eating!

Gas

The Germans first used gas against the French during the capture of Neuve Chapelle in October 1914, firing shells containing a chemical irritant that caused violent fits of sneezing. In March 1915, they used a form of tear gas against the French at Nieuport.

These early experiments were a small taste of things to come. As the war progressed. all sides developed ever more lethal gases, including chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas.

The introduction of gas warfare in 1915 created an urgent need for protective equipment to counter its effects. The British Army developed a range of gas helmets based on fabric bags and hoods that had been treated with anti-gas chemicals. These were later replaced by a small box filter respirator, which provided greater protection.

Rattles, horns and whistles were also adopted as means of warning troops and giving them time to put on protective equipment during gas attacks.

Despite all of this, British and Commonwealth forces suffered over 180,000 gas casualties during the conflict.

‘The gas hung in a thick pall over everything, and it was impossible to see more than ten yards. In vain I looked for my landmarks in the German line, to guide me to the right spot, but I could not see through the gas. Inevitably we scattered... Men were clearly disorganised and running and walking in the direction of the German trenches, looking like ghouls in their gas helmets.’Second Lieutenant George Grossmith describing the British gas attack at the Battle of Loos — September 1915

Improvised weapons

Action on the Western Front was not restricted to large-scale battles. Soldiers were often involved in trench raids - small surprise attacks to seize prisoners and enemy weapons or to gain intelligence.

For close-quarter fighting in confined spaces, many experienced soldiers preferred to use improvised clubs, knives and knuckledusters rather than cumbersome rifles. These were also more suited to silent killing.

Reminiscent of medieval weapons, these improvised items were no less deadly and symbolised the primal, brutal nature of trench warfare.

Tanks

Tanks were developed by the British Army as a mechanical solution to the trench warfare stalemate. They were first used on the Somme in September 1916, where they were mechanically unreliable and too few in number to secure a victory.

One of the few ways in which tanks were effective during the war was their ability to break through barbed wire defences. Even then, their tracks were still at risk of becoming entangled.

As the war progressed, the Army found better ways to utilise their new weapon and exploit its advantages. The tank made its first significant breakthrough when it was used en masse at Cambrai in 1917.

Technologically, the machines grew more advanced. By 1918, they were being effectively used as part of an 'all-arms' approach during the Allies' successful attacks. However, they remained vulnerable to enemy fire and were still mechanically unreliable.

It was only after the war had ended that the effectiveness of the tank as a weapon was fully realised.

‘We heard strange throbbing noises, and lumbering slowly towards us came three huge mechanical monsters such as we had never seen before. My first impression was that they looked ready to topple on their noses, but their tails and the two little wheels at the back held them down and kept them level. Big metal things they were, with two sets of caterpillar wheels that went right round the body.’Private Bert Chaney observing the first tanks go into battle — September 1916

Barbed wire

Thick belts of barbed wire were placed in front of the trenches on the Western Front. They were usually positioned far enough from the trench that the enemy was unable to throw grenades in.

Sometimes barbed-wire entanglements were designed to channel attacking infantry and cavalry into machine-gun and artillery fields of fire.

Even though it was an agricultural invention, barbed wire proved an effective military defence. It was cheap, easy to erect and effectively ensnared the enemy. It was also somewhat resistant to artillery fire, tangling together further to become more impassable. If damaged, it could simply be replaced.

‘One night we heard a cry, the cry of one in excruciating pain; then all was quiet again. Someone in his death agony, we thought. But an hour later the cry came again. It never ceased the whole night. Nor the following night... Later we learned that it was one of our own men hanging on the wire. Nobody could do anything for him; two men had already tried to save him, only to be shot themselves.’Ernst Toller, German war veteran and playwright — 1934

Grenades

Grenades were useful weapons for trench warfare as troops could throw them into enemy positions before entering. However, they were also risky in confined spaces, especially when not handled correctly. Soldiers disliked the Mark 1 Grenade (above) because it was liable to detonate if knocked against something when being thrown.

As the war developed, the Army also used rifle grenades. As the name suggests, these were fired from a rifle, rather than thrown by hand, which greatly increased their range. These were later modified to carry smoke, incendiary devices, flares and anti-tank warheads, as well as high explosive.

The ‘all-arms’ offensive

Even though the Army had a broad arsenal of weapons at their fingertips, it took them most of the war to use these fighting tools to their advantage. The stalemate was only overcome in 1918 after years spent learning new tactics that combined the effective use of these weapons.

The Battle of Amiens in August 1918, along with the subsequent Hundred Days Offensive, illustrated that the British had learnt how to combine infantry assaults (men armed with rifles, grenades and machine guns) with gas, artillery, tanks and aircraft in a co-coordinated attack or ‘all-arms’ approach.

Display of strength

You can find many of these items in our Conflict in Europe gallery. Come and see them displayed alongside other objects that help shed light on soldiers' experiences of the First World War.