A new territory

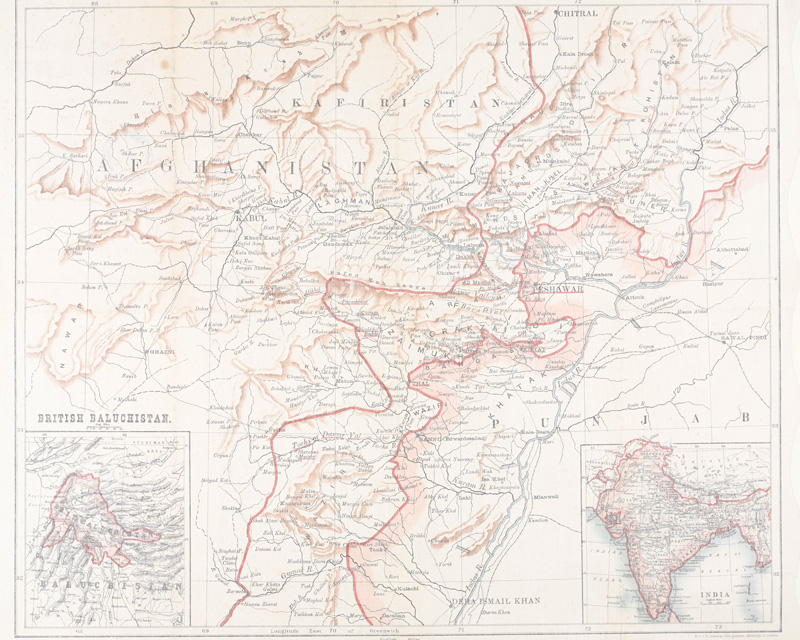

The North-West Frontier (now a region of Pakistan) became part of British India in the aftermath of the Second Sikh War (1848-49).

Following its victory in that conflict, the British East India Company annexed the Punjab. In doing so, it also became responsible for the frontier regions with Afghanistan, which had been part of the Sikh Empire’s territories. This frontier zone remained part of the Punjab until separated into the North-West Frontier Province in 1901.

The North-West Frontier was also divided into a so-called ‘settled area’ that came under direct British rule, and a largely autonomous ‘tribal area’ directly adjacent to the Afghan border. This latter zone was free from the trappings of colonial rule, such as courts, police and taxation.

Map of the North-West Frontier, 1897

Border

The North-West Frontier’s border with Afghanistan was not formalised until 1893, when the Durand Line was established. Named after Sir Mortimer Durand, who negotiated its route with the Afghan Emir, this boundary traversed many tribal areas and caused much resentment.

The Afghans soon repudiated the agreement. They continued to claim parts of the province as their own, as they indeed had been prior to Sikh rule. In the years that followed, they regularly interfered in tribal affairs on the British side of the line, hoping to regain lost influence there.

Inhabitants

Pathans constituted the largest ethnic group along the frontier. They were divided into several tribes, frequently at war with one another. The largest tribes, like the Afridi or Waziris, were also split into different clans. All of the tribes were Muslim and had strong codes of honour and hospitality.

Their mountain homelands were harsh and barren, so they often supplemented their meagre living by raiding the more prosperous settled areas to the east. Some tribes also controlled important mountain passes and either levied a charge on the trading caravans that travelled to and from Afghanistan, or looted them if they refused to pay.

'Every man, woman and child in the clan [the Zakka Khel Afridis] looks upon those who commit murders, raids and robberies in Peshawar or Kohat as heroes and champions. They are the crusaders of the nation. They depart with the good wishes and prayers of all, and are received on their return from a successful raid with universal rejoicings.'Major George Roos-Keppel, Political Agent in the Khyber — 1901

Fighters

Many Pathan tribes, such as the Afridis, Orakzais, Mahsuds and Waziris, fiercely resisted British-Indian forays into their territories. Highly mobile, tactically astute and sharp shooters, they were perfectly adapted to their environment. Only experienced and well-trained British and Indian units could match them in frontier fighting.

The British were so impressed by the fighting qualities of the various Pathan tribes that they went to great lengths to enlist them into the Indian Army and their various frontier militias.

‘The Mahsud or Wazir is an expert at attacking convoys or small detachments and is assisted by the nature of his country, the ravines being narrow and winding, while the hillsides… are often thickly covered in bushes. He attacks systematically, with special parties being told off for specific duties, such as the neutralisation of adjacent picquets by fire, support to his advanced parties of swordsmen etc. Ambushes may sometimes open by a few shots from one side of a nullah. Untrained troops rush to cover on the side from which the fire comes. This is what is waited for. Heavy accurate fire from the other bank then finishes the party.’Pamphlet issued by HQ Waziristan District — 1924

Aims

The British had two main aims in dealing with the North-West Frontier.

The first was to prevent raiding from the mountains into the settled, law-abiding lowland areas. By punishing recalcitrant tribes, they were able to maintain British prestige and ensure that the subjects of British India would continue to believe in the political will and military power of their rulers.

The second major aim was to prevent a Russian invasion from the north-west. Throughout the 19th century, Russia expanded its domains through Central Asia, coming ever closer to India. This potential threat continued to occupy the minds of British policy makers.

There was disagreement as to how these aims could be achieved. But two schools of thought emerged.

‘Close Border’ policy

Supporters of the ‘Close Border’ policy argued that it was best to have as little to do with the tribal areas as possible, to manage the tribes and mount expeditions against them if they offended.

To counter any invasion threat, they argued that it was better to wait, well supplied, on the line of the River Indus and let the enemy deal with the problem of both the mountains and the tribes.

Favoured by the Punjab government, this approach generally prevailed for the first three decades of British rule.

‘Forward’ policy

Advocates of the ‘Forward’ policy called for a more active intervention in tribal affairs. They pointed out that if the British controlled the passes leading into India from Afghanistan, its forces would be better placed to deal with any Russian invasion.

This approach, which came to the fore between the late 1870s and the 1900s, led to many forays into the tribal areas. It also caused a full-scale invasion of neighbouring Afghanistan in 1878 - which further served to inflame the border tribes - and brought about the eventual delineation of the border with that country from 1893 onwards.

This period also witnessed the building of a system of advanced garrisons in forts spread across the tribal areas, as well as the creation of political agencies to oversee many of the region’s semi-independent rulers.

A change of tack

But as time progressed, the ‘Close Border’ policy returned. From around 1900, the government of India became unwilling to continue expending resources on a barren and largely unprofitable backwater. Relations with Russia also improved so the invasion threat receded.

Most regular troops were pulled back from the tribal areas, which were left to be policed by locally-recruited militias under the command of attached Indian Army officers. These included units like the Khyber Rifles and Tochi Scouts. The militias provided a useful intelligence and political link between the British and the local tribes.

Khasadars

From the late 1890s, the British also appointed khasadars, who had the responsibility of maintaining law and order in the tribal areas.

These were also commanded by officers on attachment from Indian Army units. But the selection of rank-and-file khasadars was left to the tribes, who chose the most respected men in their communities to be their protectors.

The khasadars had the power to arrest, call for tribal jirgas (councils) or dispense justice on the spot, if offenders put up resistance.

Patrols

From 1915, the khasadars and militias were reinforced by the Frontier Constabulary, which guarded the border between the tribal and settled areas.

The militias, khasadars and constabulary carried out patrols. But in the case of more serious action, they could call upon movable columns of regular troops from large military cantonments, like Peshawar and Kohat, or from the garrisons that remained in strategically vital spots, like the Khyber Pass and Razmak in Waziristan.

Frontier control

In 1925, the Khyber Pass Railway was opened. This ran from Jamrud, near Peshawar, to the Afghan border near Landi Kotal, allowing easier movement of troops to the frontier districts.

Until the end of British rule in 1947, the tribal areas remained largely autonomous. But the poverty of the region meant that tribesmen still resorted to regular raiding into the settled areas. The cycle of punitive expeditions went on, although to a lesser extent than in the late 19th century.

Punjab Frontier Force

Whether it was the 'Forward' or 'Close Border' policy that was currently in vogue, one formation was usually engaged somewhere on the frontier. The Punjab Frontier Force (PFF) was formed in 1851 as the Punjab Irregular Force to police and protect the newly acquired frontier. It was called ‘Irregular’ because it was outside the control of the East India Company’s army, reporting instead to the Chief Commissioner of the Punjab.

Many of its units were raised by proteges of Colonel Sir Henry Lawrence, the first British leader of the Punjab following the Sikh Wars. Men like Captain John Coke, Lieutenant Harry Lumsden and Lieutenant William Hodson helped lay the foundations of British rule on the North-West Frontier.

In later years, PFF regiments were fully integrated into the Indian Army. But their early independence allowed them to reject formal drill and regular tactics in favour of developing swift-moving soldiers who could live and fight in rough country.

Khaki

The PFF included elite units like the Queen's Own Corps of Guides (raised in 1846). This consisted of a unique combination of infantry companies and cavalry squadrons.

The Guides were the first military force to adopt khaki uniform. Realising how impractical Army uniforms were, both for ease of movement and camouflage, their founder, Harry Lumsden, obtained cotton fabric which was dyed with river mud.

The result was a loose-fitting uniform which, because of the yellowish dust-colour of the fabric, provided useful camouflage on the frontier. The Persian word for dust was ‘khaki’ and was adopted for this innovative colour.

'After today we begin to burn villages. Every one. And all who resist will be killed without quarter. The Mohmands need a lesson.’Lieutenant Winston Churchill — September 1897

Punitive expeditions

On the whole, punitive expeditions were employed as a last resort, when other methods such as bribes (officially known as subsidies), blockades, fines and seizures of goods had failed. Normally, an expedition would destroy crops, water tanks, forts or villages to force a tribe to hand over criminals or pay compensation.

Most expeditions involved a combination of men from the Punjab Frontier Force, locally raised levies led by British officers, and regular British, Indian and Gurkha troops. Artillery batteries, equipped with light movable mountain guns, often provided extra firepower.

3-11 December 1849

Baizai Expedition

February-November 1850

Kohat Expedition

April 1852

Mohmand Expedition

December 1852

Waziristan Raid

December 1852-January 1853

Black Mountain Expedition

August 1854

Mohmand Raid

April-May 1855

Miranzai Valley Expedition

March-May 1860

Mahsud Reprisal

Umbeyla, 1863

This operation, between 20 October and 23 December 1863, was directed against Muslim tribesmen in Sittana, and focused on the village of Malka. The tribesmen had harboured Indian mutineers in 1857. More than a decade later, they were still resisting British rule.

The Yusafzai Field Force, under General Sir Neville Chamberlain, advanced up the Umbeyla (or Ambela) Pass against strong opposition from the Bunerwal tribe. Heavy casualties were sustained during attempts to hold the 'Eagle's Nest' and 'Crag Piquet'.

The troops were organised into two brigades which drove the tribesmen out of the valley. A small party then burnt Malka. The expedition suffered 238 dead and 670 wounded. Tribal losses were estimated at more than three times those sustained by the British.

July-October 1868

Black Mountain Expedition

March 1872

Tochi Valley Expedition

August-December 1877

Jowaki Expedition

February 1878

Utman Khel Reprisal

1878-1881

Second Afghan War

November-December 1883

Shiranni Expedition

Black Mountain, 1888-91

Raiding by tribesmen from the Black Mountains - at the northern edge of the Punjab frontier - culminated on 18 June 1888, when a British patrol was ambushed and two officers killed. Five columns of the Hazara Field Force under Major-General JW McQueen then advanced into the rebellious area on 4 October.

The Akazais and Hassanzais were brought under control, and on 13 October a village of ‘fanatics’ at Maidan was destroyed. McQueen then moved on to punish the remaining hostile tribes. Operations were concluded by 14 November.

Three years later, another expedition was required against the Akazais and Hassanzais to enforce the peace terms of 1888. Three brigades under Major-General WK Elles were deployed between March and May, destroying several villages.

October-November 1890

Zhob Valley Expedition

January-May 1891

Miranzai Expedition

December 1891

Hunza-Nagar Expedition

November 1894-March 1895

Waziristan Expedition

Chitral, 1895

The adoption of the ‘Forward’ policy led to an escalation of violence in the 1890s. In early 1895, the British sent a force to Chitral, under the command of the political agent Surgeon Major George Robertson, to oversee the transition of power there after a ruler had been murdered.

Their endeavours were unsuccessful and an uprising began. Robertson and his men retreated to a small fort, which was promptly besieged by tribesmen. They held out for six weeks while two columns marched to their aid.

The larger column, 15,000 British and Indian troops under Major General Sir Robert Low, fought their way through the Malakand Pass and up the Swat Valley, while 500 men of the 32nd Punjab Pioneers under Lieutenant-Colonel James Kelly set off from Kashmir, 200 miles away.

Despite having to march across wild, snow-covered terrain, Kelly’s men reached Chitral first. On 20 April, they found Robertson and his 300 men still fighting on. Soon after, Low’s force arrived to disperse the remaining tribesmen.

The 1897 Rising

In 1897, the British faced their greatest challenge when nearly all the Pathan tribes of the frontier rose up in rebellion. Partly caused by fears about the Durand Line, which they believed presaged full British annexation, the violence was also stirred up by several mullahs calling for a jihad, or holy war.

Outlying forts and garrisons were attacked and several major expeditions had to be launched. The first outbreak occurred on 10 June 1897, when the military escort of the Tochi Political Agent was attacked at Maizar. A force under Major-General G Corrie Bird was then assembled which traversed and occupied the Tochi Valley until January 1898.

Malakand Field Force

Shortly after, in July 1897, around 12,000 tribesmen attacked and surrounded Malakand and Chakdara forts in the Swat Valley, which guarded the Chitral road. The Indian Army garrisons held out and were relieved after a week of day and night assaults.

At Chakdara, 240 troops from the 11th Bengal Lancers and 45th Sikhs were estimated to have killed over 1,000 tribesmen, for the loss of only five dead and 10 wounded.

Three brigades were then despatched under General Sir Bindon Blood, who mounted punitive expeditions against the local tribesmen until late October 1897.

Mohmand Field Force

On 7 August 1897, the Mohmands attacked Shabkadr Fort, which was only only a few miles from the provincial capital Peshawar. Its garrison held out until relieved by the Peshawar Movable Column.

The Mohmand Field Force was then formed under Brigadier-General E Elles, which imposed peace and fines upon the rebellious tribes during September and October.

Samana

In September 1897, a force under Brigadier-General A Yeatman-Biggs moved against the Afridis and Orakzais in Kohat district, following attacks on several posts there.

At Saragarhi post, on the Samana Ridge, 21 soldiers of the 36th Sikhs fought to the last man rather than surrender or try to flee. Although the fort fell, most of the other posts held out until relieved by Yeatman-Biggs.

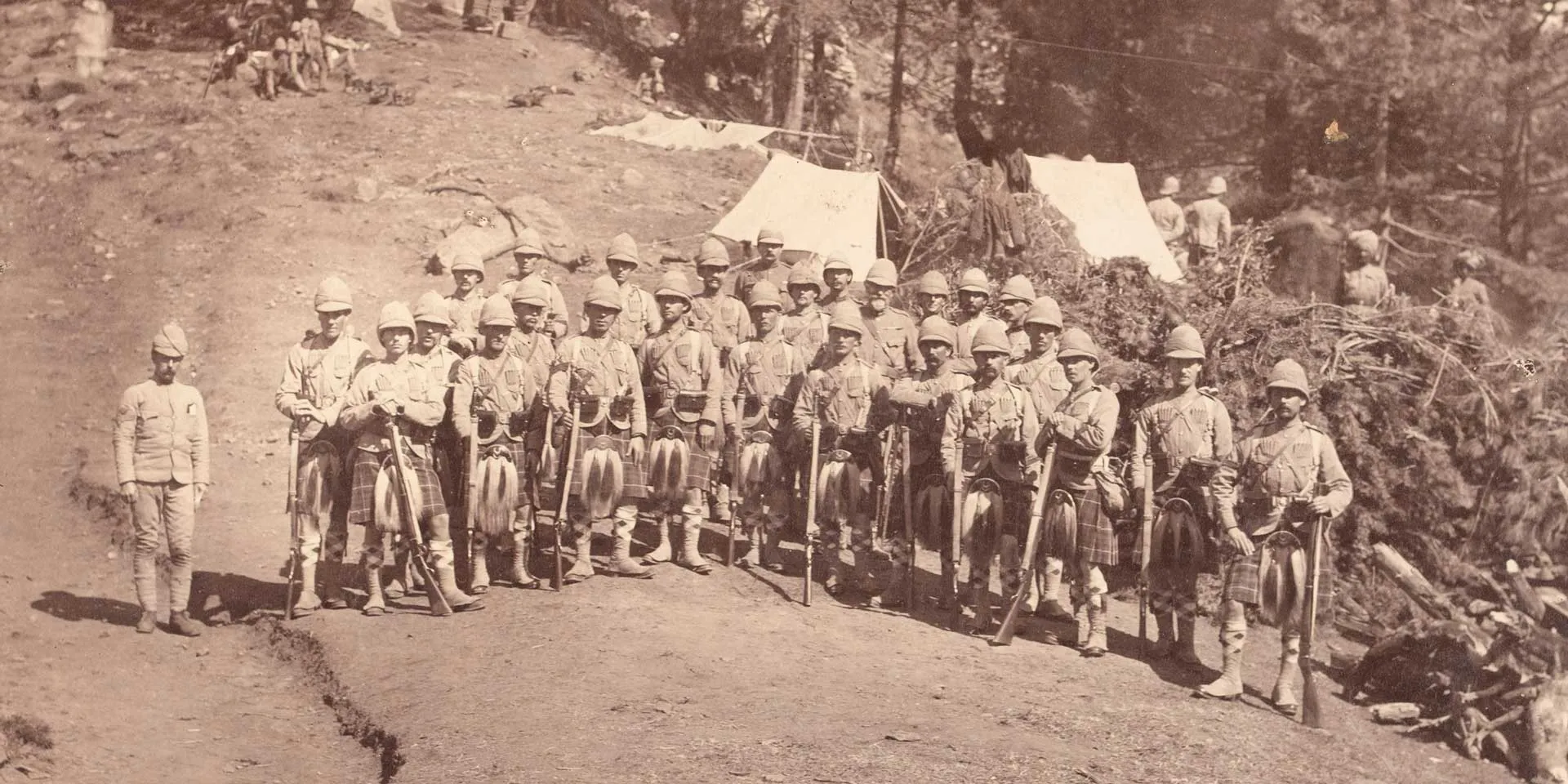

Tirah Field Force

The largest operation, involving 35,000 troops and 20,000 camp followers, under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir William Lockhart, was mounted in October 1897 against the Afridis and Orakzais in the Tirah. The two tribes had attacked several forts, but also captured posts in the Khyber Pass, which bordered the north of their territory.

As Lockhart’s main force crossed the Samana Mountains, it found its route blocked by 12,000 tribesmen occupying a steep ridge at Dargai. Lockhart’s infantry suffered heavy casualties in the open ground in front of the Afridi positions, but the ridge was eventually stormed by the 1st Gordon Highlanders and 1st/2nd Gurkhas to the sound of Piper George Findlater's bagpipes.

Lockhart’s force then fought its way into Tirah and established a fortified camp at Maidan. From here, columns were sent out to pacify the surrounding valleys and regain control of the Khyber Pass. The expedition lasted until January 1898 and cost the British 287 dead and 853 wounded.

December 1900-March 1902

Mahsud Blockade

November-December 1902

Kabul Khel Expedition

February-March 1908

Bazar Valley Campaign

April-May 1908

Mohmand Campaign

November 1914–March 1915

Tochi Valley Operations

April-September 1915

Campaign against the Mohmands and Bunerwals

June-July 1917

Operations against the Mahsuds

Waziristan, 1919-22

In 1919, the Afghans invaded the North-West Frontier. Although the British quickly defeated them, many of the frontier tribes rose up in response, especially those in Waziristan.

Over 10,000 troops from the Indian Army took part in the campaign to re-establish British control of the border areas and 1,300 men were killed in action or died from their wounds and sickness. Although there was much heavy fighting on the ground, the British bombing of Wazir and Mahsud villages eventually brought the conflict to an end in 1922.

The difficulties they had experienced in Waziristan made the British establish a self-contained cantonment capable of holding 10,000 men at Razmak. The force there included the Razmak Movable Column (RAZCOL), consisting of a strong all-arms brigade with pack transport, that could quickly patrol the surrounding region.

The British also embarked on a road-building programme to improve military access to the most unruly tribal areas in Waziristan.

June 1927

Operations against the Mohmands

1930-31

Afridi raids and Pathan Redshirt Rebellion

July-October 1935

Mohmand Campaign

Waziristan, 1936-39

In 1936, the Waziri leader Ghazi Mirzali Khan Wazir, nicknamed the Fakir of Ipi by the British, launched a jihad against British rule. His activities soon threatened communications with Razmak garrison. Over 30,000 troops, together with aircraft and armoured cars, were then deployed against his followers.

The Fakir’s men were skilled at guerrilla warfare. Knowing that the British would not cross an international boundary, they frequently took refuge behind the Durand Line which divided British tribal territory from Afghanistan. During an April 1937 attack, a British convoy of vehicles, escorted by six armoured cars, was ambushed in a narrow defile at Shahpur Tangi. Seven officers and 45 men were killed, while another 47 were wounded.

Pursuit

The Fakir's headquarters was eventually captured, although he himself escaped. British troops continued to pursue his men well into the 1940s.

He remained a thorn in the sides of the British and later the Pakistan authorities until his death in 1960. For many years, the Fakir also campaigned for an independent Pathan homeland.

The video below shows British-Indian troops in Waziristan during the campaign against the Fakir of Ipi in 1941-42.

A tough school

Between the two World Wars, operations on the North-West Frontier gave British and Indian soldiers the rare opportunity to practise their military skills under active-service conditions.

Indeed, many British officers who went on to distinguish themselves during the Second World War (1939-45) honed their leadership skills in the passes and hills of the frontier. These included Claude Auchinleck and Harold Alexander, the commanders of the Peshawar and Nowshera Brigades in the 1935 Mohmand expedition.

Independence

In the months leading up to India and Pakistan’s independence in 1947, British and Indian troops supervised a referendum across the North-West Frontier to decide which country the province would join. Some inhabitants wanted an independent Pathan state or amalgamation with Afghanistan, but this was not an option on the ballot. They voted to join Pakistan.

Soon after, the British executed a well-planned and orderly withdrawal from their bases in Waziristan and the other tribal regions. But newly independent Pakistan faced the same problems as the British when it came to enforcing law and order on the tribes there.

To help police the region, the new Pakistan Army retained the old units of the Punjab Frontier Force (later retitled as The Frontier Force Regiment). The tribal area remained semi-independent and was renamed the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA).

Recent years

In 2001, British soldiers deployed to Afghanistan alongside the US and other allies to destroy al-Qaeda - the group behind the ‘9/11’ terror attacks - and the Taleban regime which supported them. As the Afghan conflict raged, British troops also returned to the North-West Frontier to counter the activities of al-Qaeda, Taleban and Pakistani Islamist militants within the FATA.

While Special Forces troops hunted down militants, other soldiers helped train members of Pakistan’s Frontier Corps. This force includes units such as the Chitral Scouts, Khyber Rifles, Kurram Militia, Tochi Scouts and South Waziristan Scouts, all of which originated during the British colonial period.