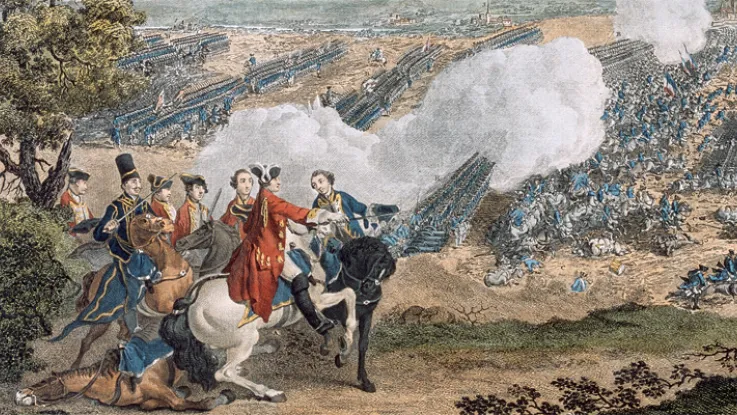

Dettingen and Culloden

James Wolfe (1727-59) was born at Westerham, Kent, the eldest son of Lieutenant-General Edward Wolfe. He was a career soldier and entered the Army in 1741 aged 14. At the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, he caught the attention of the Duke of Cumberland, who then helped to promote Wolfe’s early career.

Wolfe fought at Culloden in 1746 and saw further service in Scotland and Ireland during the 1750s. His tactical theories and significant improvements to firing and bayonet techniques were an important part of his legacy and were posthumously published as ‘General Wolfe’s Instructions to Young Officers’ (1768).

Rochefort and Louisbourg

During the Seven Years War (1756-63), Wolfe distinguished himself during the aborted assault on Rochefort in 1757, going ashore to scout the terrain prior to the raid. He also tried to persuade the commander of the operation, General Sir John Mordaunt, to act more decisively. Wolfe informed Mordaunt that he could capture Rochefort if he was given just 500 men. But the general refused him permission.

He again came to prominence at the siege of Louisbourg in 1758, commanding a brigade there with great skill. This led to his appointment, at the age of 32, as major-general in command of the Quebec expedition in 1759.

‘Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals.’King George II on James Wolfe — 1759

Quebec

Wolfe experienced months of frustration and ill health, and many thought the expedition was doomed to fail. But at dawn on 13 September, he led his men in the execution of a daring plan.

Using flat-bottomed landing craft, he took his 4,500 troops up the St Lawrence River and landed them south-west of Quebec. They then scaled the Heights of Abraham to surprise the French and draw them out of the city and into battle precisely where Wolfe wanted to fight.

It was a risky venture that relied on a mixture of luck and good judgement. But it worked.

Double volley

After skilfully positioning his men behind a ridge, to protect them from the French batteries inside the city walls, Wolfe ordered his soldiers to double-load their muskets for a devastating initial volley. In the brief fight that followed, their fire drove the French back into the city.

Wolfe was fatally wounded early in the battle but lived long enough to hear of his victory. He was an inspirational leader, who, like other great generals, was loved by his men.

‘I can’t compare it to any thing better, than to a family in tears and sorrow which had just lost their father, their friend and their whole dependance.’Lieutenant Henry Browne, who held Wolfe as he lay dying, in a letter to his father — 1759

Martyr

When news of Wolfe’s death reached Britain, it seized the public imagination. He was seen as a young, heroic martyr and a paragon of martial virtue.

As the greatest military hero of the mid-18th century, Wolfe was universally celebrated in paintings, prints and other forms of popular culture.