Explore more from In Their Own Words

In Their Own Words: Lieutenant Colonel John Blackader

7 minute read

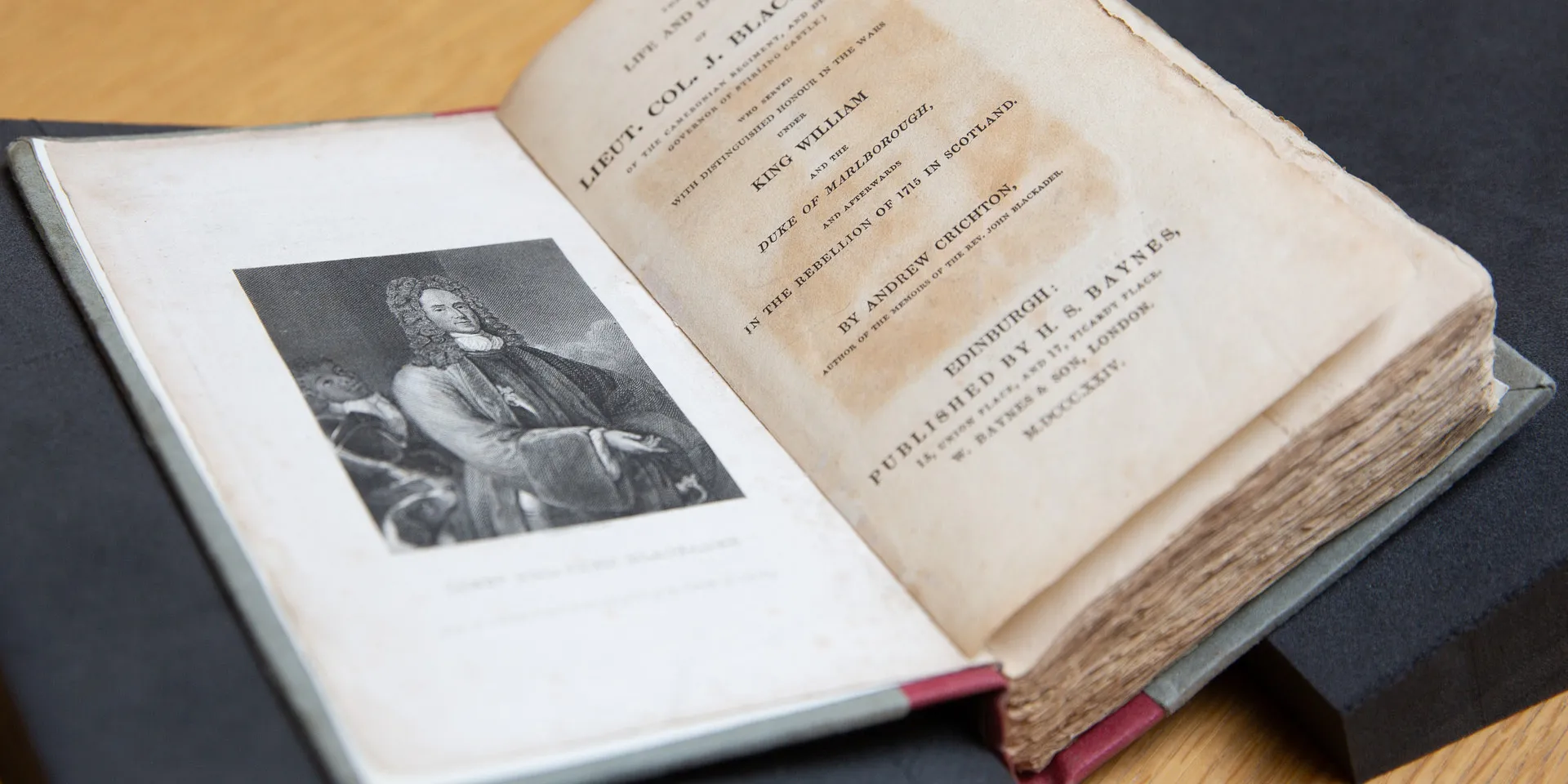

The Life and Diary of Lieutenant Colonel John Blackader

A Christian and a soldier

John Blackader was born in the Parish of Glencairn, Dumfriesshire in 1664, the youngest of five brothers. Although his family were of noble lineage, their fortunes had long been in decline and they enjoyed no wealth or landholdings.

Blackader grew up in an age of intense religious fervour and conflict. His father was a Presbyterian minister, who suffered persecution because of his opposition to the Scottish church being governed by bishops, a policy pursued by consecutive Stuart monarchs, Charles II and James II. Proclaimed a rebel, he ultimately suffered imprisonment on Bass Rock, an island in the Firth of Forth, where he died in 1685.

Despite his father’s trials and tribulations, John Blackader inherited a strong Christian faith. He also received a good education, which he completed at Edinburgh University.

In 1689, he joined the Earl of Angus's Regiment, popularly known as 'The Cameronians'. This was a staunchly religious unit formed from followers of Richard Cameron, the martyred leader of a militant band of Presbyterians known as Covenanters.

Jacobite rebellion of 1689

By this time, the political and religious climate in Britain had been transformed by the upheaval of the 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688. This resulted in James II being deposed and replaced on the throne by his daughter, Mary II, and her husband, William III.

The Cameronians were loyal to William and Mary. In August 1689, they were called upon to fight against James’s supporters - the Jacobites - who had risen in rebellion.

The two forces clashed at Dunkeld, north of Perth. Here, despite being heavily outnumbered, Blackader's regiment succeeded in driving back their enemies, inflicting a defeat which effectively ended the rebellion in Scotland.

On the Continent

In the decades that followed, Blackader saw extensive service with the Cameronians in continental Europe, serving first under William III and then John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough, during both the Nine Years War (1689-97) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-13).

He was present at many of the most famous engagements of the age, including Namur (1695), Blenheim (1704), Ramillies (1706), Oudenarde (1708), Lille (1708) and Malplaquet (1709). A courageous and conscientious officer, Blackader rose steadily through the ranks, becoming lieutenant colonel and regimental commander in 1709.

‘Grenadiers, in the name of God, attack!’John Blackader, diary entry recounting the assault against the city of Lille — September 1708

A spiritual register

While it's unclear exactly when Blackader began his diary, the surviving material starts in 1700 and ends in 1728.

Keeping a diary in this period was unusual, but it seems clear that religion was a motivating factor. Like other Protestant Christians, Blackader found that recording his thoughts and feelings helped him monitor the progress of his religious development.

His writings reveal the mental anguish resulting from the constant battle between his conscience and worldly temptations.

‘My life is a struggle, as it were, between faith and corrupt nature – a combat, in which sometimes strengthening grace prevails, sometimes earthly affections and sensual appetites gain ground.’John Blackader, diary entry — October 1700

Tyranny and knavery

Blackader’s diary provides comparatively little information about the campaigns in which he fought. However, it does provide a unique insight into Army life in this period.

It brings into focus the vices and rough manners of his comrades which, for him, were a particular cause for complaint. It also reveals the unscrupulous methods used for recruiting, which jarred severely with Blackader’s faith and character.

‘This is a sad corps I am engaged in; vice raging openly and impudently. They speak just such language as devils would do. I find this ill in our trade, that there is now so much tyranny and knavery in the army, that it is a wonder how a man of a straight, generous, honest soul can live in it.’John Blackader, diary entry — June 1703

‘This vexing trade of recruiting, depresses my mind... I cannot ramble, and rove, and drink, and tell stories, and wheedle, and insinuate, if my life were lying at stake.’John Blackader, diary entry — February 1705

Blood guilt

On occasion, Blackader’s faith presented him with deep moral quandaries. While serving at Maastricht in 1691, he was challenged to a duel by Lieutenant Robert Murray. Unable to extricate himself from the situation, Blackader was compelled to kill his fellow officer in an act of self-defence.

He was court-martialled, but then pardoned as witnesses were able to clarify the circumstances. Nonetheless, this was an episode that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Later, when challenged once again, he risked dishonour to avoid having to take another life.

‘We came to Maastricht in the evening… at night I went alone to visit that spot of ground, as near as I could find it, where twelve years ago, I committed that unhappy action. There I fell down on my knees, and prayed as I had done several times throughout the day, that God would deliver me from blood-guiltiness.’John Blackader, diary entry — April 1703

Divine providence

Blackader’s religious scruples gave him no such qualms about killing an enemy. Indeed, he was often in the thick of the fighting and was wounded on several occasions. At Blenheim, he suffered a throat injury, which could easily have been fatal. At the Siege of Lille, while courageously leading an assault, he received bullet wounds to the arm and head.

Like most soldiers on campaign, Blackader was exposed to various other hardships and dangers. He nearly drowned on two occasions during river crossings, and the threat of disease was ever-present.

Religion profoundly shaped his interpretation of these near-death experiences, which he classed as 'Ebenezers', or providential deliverances from danger. His diary is full of praise and thankfulness towards God for his many escapes. He further extended this system of belief to his understanding of the outcome of battles and the fate of nations.

‘Among the rest I have also got a small touch of a wound in the throat; but this, so far from making me doubt of the care of Providence, is really to me a great confirmation, and a remarkable instance of his protection; for the wound is so gently and mercifully directed, that there is no danger; whereas, if it had been half an inch either to one side or other, it might have proved mortal or dangerous.’John Blackader, diary entry — August 1704

Later life

Blackader retired from the Army in 1711. He returned to Scotland, living first in Edinburgh and then in Stirling with his wife, Anne, whom he had married in 1702.

He kept up an active religious life, becoming an elder of the College Church of Edinburgh and a member of both the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

He briefly resumed his military career during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715, taking command of a regiment raised by the city of Glasgow. He was rewarded for this service with the post of deputy governor of Stirling Castle.

John Blackader died in 1729 and was buried in the West Church of Stirling.

A literary legacy

Blackader had no children. Instead, his diary has proved to be his most significant legacy. After his death, it passed to his wife, who remarried. It then lay forgotten and neglected for many years and was eventually sold, along with his letters, to a local tobacconist.

Fortunately, this trader recognised the value of Blackader's papers and passed them on to scholars, eventually resulting in their publication during the 19th century as 'The Life and Diary of Lieutenant Colonel John Blackader'. A digitised version is freely available to access online via the Internet Archive.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.