Family influence

Sitaram Pande (or Sita Ram Pandey) was born in 1797 in Tilowee, a village in the Kingdom of Oudh (now part of Uttar Pradesh) in northern India. His family were Brahmins, the highest social class in Hindu society, and his father was a yeoman farmer of some local standing.

Had he stayed at home, Pande could have looked forward to a life of relative comfort and social prestige. However, Oudh was one of the principal recruiting grounds for the Bengal Army and the draw of military service would prove too strong for him to resist.

Pande had an uncle who had already joined up. While visiting on leave, he had intoxicated his nephew with tales of military adventure. Determined to follow in his uncle’s footsteps, Pande overcame opposition from his mother and his local priest, before enlisting and embarking upon what would turn out to be a remarkable career.

‘My uncle was a very handsome man, and of great personal strength. He used of an evening to sit on the seat before our house, and relate the wonders of the world he had seen, and the prosperity of the great Company Bahadur [the East India Company] he served, to a crowd of eager listeners, who with open mouths and staring eyes took in all his marvels as undoubted truths. None of his hearers were more attentive than myself, and from these recitals I imbibed a strong desire to enter the world and try the fortune of a soldier.’Sitaram Pande recounting his motivation to join up

The East India Company

At this time, the East India Company was already a major political and military power in India. During the period of Pande's service, it would extend its control over much of the subcontinent. This was achieved through three ‘Presidencies’ - Bengal, Bombay and Madras - each with its own army.

Joining the ranks

As a result of his uncle’s stories, Pande was in awe of the British and their armies. However, on entering service, he suffered a rude awakening. He found the medical inspection unpleasant and humiliating, and he was bullied mercilessly by his drill instructor during training.

Gradually overcoming a desire to run away, he worked diligently to learn his new trade. After eight months, he was able to join the ranks of his regiment.

‘I had to attend drill for many months, and one day happened to forget how to do something and was so severely cuffed on the head that I fell down senseless.’Sitaram Pande on drill training

Early campaigns

The early years of Pande’s military career were particularly intensive. He saw action during the Gurkha War (1814-16) in the Kingdom of Nepal, and then took part in the operations against the Maratha Empire and the Pindaris in central India during what became known as the Third Maratha War (1817-19).

During the Nepalese campaign, Pande’s unit suffered many casualties, and then experienced a terrifying incident when their camp was stampeded by a herd of wild elephants. While fighting against the Pindaris, Pande was badly wounded and separated from his unit. With the help of local people, he survived 13 days in hiding, before eventually being rescued.

Romance and tragedy

The events of the Third Maratha War would bring Pande joy and suffering in equal measure. During an operation to clear the village of Ahanpura, he burst into a house and killed an Arab mercenary who was about to murder a young woman. Captivated by her beauty, Pande fell in love. He would later take her as his second wife, and she would bear him a son.

However, tragedy followed, when his unit was devastated by an exploding magazine during their advance to occupy the fortress of Asirgarh in 1819. Pande suffered serious injuries, including a broken arm and several head wounds. His uncle was killed, and his body was never recovered.

‘He came at me so frantically that he transfixed himself on my bayonet before I could recover my surprise. I then fired my musket and blew a great hole in his chest, but even after this he managed in his dying struggles to give me a severe cut on my arm. These men live like Jackals, and they fight like Ghazis [warriors defending the Muslim faith].’Sitaram Pande recounting the rescue of the woman he would later marry

Afghanistan

In 1839, Pande took part in an ill-fated invasion of Afghanistan, which the British had embarked upon to curtail Russian influence in the region. Although largely unopposed, their advance through the mountains into this hostile country was hard. However, trouble began in earnest after they had occupied the capital, Kabul.

The British commanders and their puppet Afghan ruler, Shah Shuja, neglected their defences and badly mishandled their relations with the Afghan tribes. In the bitter winter of 1842, they were compelled to undertake a desperate retreat. Under constant attack from tribesmen, the British column was all but annihilated.

Pande was wounded and taken back to Kabul, where he was sold into slavery. A few years later, he managed to escape with the help of a merchant. But it was only with great difficulty that he was able to rejoin the Army.

‘We went on fighting and losing men at every step of the road. We were attacked in front, in the rear, and from the tops of hills. In truth it was hell itself. I cannot describe the horrors. At last we came upon a high wall of stones that blocked the road; in trying to force this, our whole party was destroyed. The men fought like gods, not men, but numbers prevailed against them.’Sitaram Pande describing events during the 1842 retreat from Kabul

Sikh Wars

During the latter half of the 1840s, Pande served in the Punjab region in the wars against the Sikhs. The British were ultimately successful, but came perilously close to defeat in several battles against the disciplined and well-equipped Sikh Army.

Pande took part in several of these hard-fought engagements, including at Ferozeshah in December 1845. He recalled that here, for the first time, he feared that the Company’s army would be overwhelmed in open battle.

‘This was fighting indeed – I had never seen anything like it before! Volleys of musketry were delivered by us at close quarters, and were returned just as steadily by the enemy... I saw two or three European regiments driven back by the weight of artillery fire which rained down on us like a monsoon downpour. They fell into confusion, and several sepoy regiments did the same. One European regiment was annihilated – totally swept away – and I now thought the Sirkar’s [the East India Company’s] army would be overpowered. Fear filled the minds of many of us.’Sitaram Pande recounting the fighting at Ferozeshah

Mutiny

Pande’s greatest trial came towards the end of his career, during the Indian Mutiny (1857-59). This conflict has complex origins, but was rooted in a widespread fear that the British posed a threat to the religions and customs of the Indian people.

The spark was the issuing of a new rifle, the cartridges of which were rumoured to be greased with beef and pork fat, offensive to both Hindus and Muslims. A mutiny among sepoys (Indian soldiers) in Meerut soon spread, growing into a wider uprising against British rule, which engulfed much of northern India.

Divided loyalties

These events placed Pande in a dreadful dilemma. He sympathised with the grievances of the mutineers, but his long service with the Company had ingrained a deep loyalty to the British and he could not bring himself to rebel.

Seized as a traitor by his mutinous comrades, he was lucky not to be killed on the spot. Instead, he was put in chains to be taken to Lucknow, where he expected to be tortured and executed. However, he was fortunate to be rescued by British cavalry operating in the area. After joining a new regiment at Cawnpore (Kanpur), he took part in operations to suppress the rebellion.

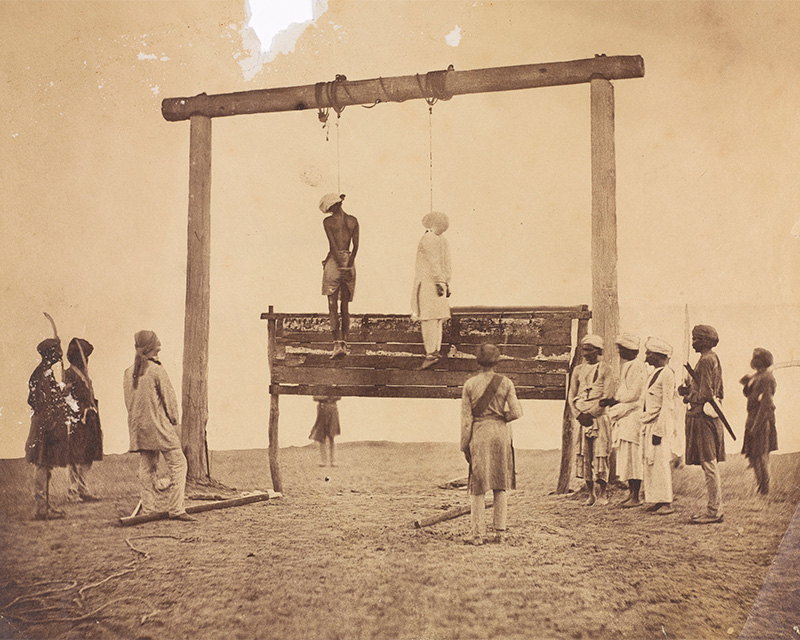

A terrible assignment

At the end of the uprising, Pande was confronted with a most terrible assignment. Not only was he directed to execute former comrades who had mutinied, he also discovered that one of them was his own son, whom he had long thought dead.

Unable to bring himself to carry out the execution, Pande was eventually relieved of this awful duty by his commanding officer. But his son was still executed.

‘I shall never forget this terrible scene. Not for one moment did I consider requesting that his life should be spared – that he did not deserve. Eventually the Major came to believe in the truth of my statement and ordered me to be relieved from this duty. I went to my tent bowed down with grief...’Sitaram Pande recounting the task of executing his own son

Retirement

Following the Mutiny, Pande was promoted to subedar, the second-highest rank an Indian soldier could attain. However, by this time, he was too old to carry out his duties and was eventually able to obtain his discharge and pension.

His commanding officer, Major James Norgate, aware of Pande’s incredible career, encouraged him to record his memoirs. Norgate then had them translated into English and published under the title 'From Sepoy to Subedar'. A digitised version is freely available to access online via the Internet Archive.

A sepoy’s perspective

Pande’s account sheds light on the battles and campaigns in which he fought, but also on the lives of Indian soldiers and their attitudes towards their British officers. It reveals how perplexing some of the British laws and customs could be, and highlights some of the challenges posed by the caste system.

Pande also provides a valuable perspective on the evolution of the Bengal Army during this period. He remarks on both its formidable fighting power and its weaknesses, in particular the deterioration in discipline which paved the way for the outbreak of the Mutiny.

Although the loss of the original manuscript has led some historians to question the authenticity of Pande’s work, it is generally believed to be genuine. Now regarded as a classic, it is the only account by a 19th-century Indian soldier known to have been published.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.