Transcript: Evacuation

Audio transcript

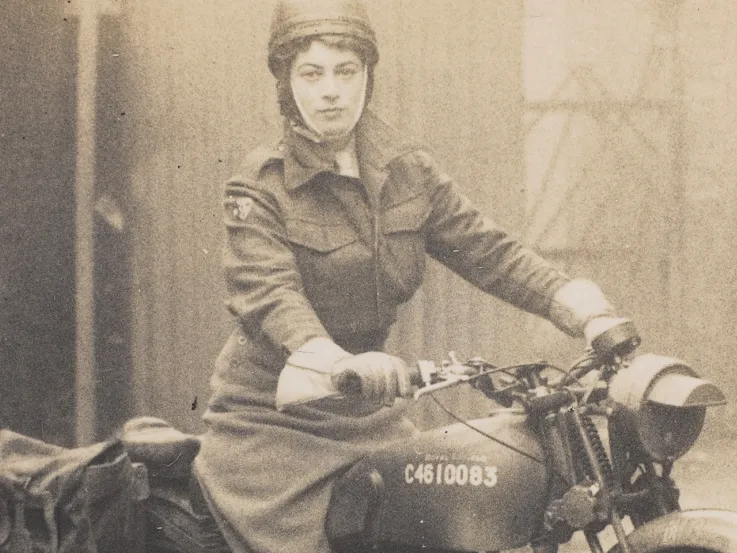

Mary Coomer:

And a girl, a French girl, who was 16 and whose parents kept a shop, a flower shop, on the corner of Place de la République, used to meet me and walk up to the office with me. She used to speak to me in English and I had to answer her in the French. So it was quite... Hélène Charnassé [?] she was called.

And she said to me one morning when we were walking, 'On our radio this morning, we hear that the Germans are right through Belgium, that means they will be near our Maginot Line and my parents are very worried, especially as I have one brother who is not quite 18, and he will now be called up,' because they were calling up a lot of the younger French people. So we really knew then that apart from picking up bits and pieces from the signals, people in the telephonists, it really was happening, so we had to get prepared to move.

And we had a meeting in the house, where we were billeted. All the officers came and we were told that we had to stand by for evacuation. We, in no way, could we try to go up north, although the first lot did go, I don't know where they went from, but first lot from Le Mans went about 10 or 12 June and we were left behind: the cooks, orderlies, clerks, all the headquarters staff and the French speakers. Then we were told we were going to be put on a train.

We only... we had to take a bottle full of water, our respirator and steel helmet and only the things that we could carry ourselves, it was not to be relied on any of the men whatsoever because they were fighting the rear guard, they were not leaving until after us.

By this time, refugees were pouring through Le Mans, it was pitiful to see them - whole families with mattresses on wheelbarrows on the tops of cars, on carts. And we were taken to a Le Mans station, which was quite a distance from where we were billeted, and put on a train, I think it was 13 or 14 June.

By this time we had heard on the radio about the people going from Dunkirk and how all the little ships and everybody had come over, 25 May, I know that was, I'm nearly sure that was right, that was when Calais fell. And then they were still bringing people, I think Dunkirk lasted 'til about 4 June wasn’t it, 4 or 6 of June, they started to come over from the end of May, when they were evacuating all the troops from up there.

So they put us on this train and we were absolutely piled in and all I can remember, one of the movement control of people saying, 'Wherever you get to, you must get the ATS onto a ship of some kind if possible, because if they are left behind and they're in uniform, they will go to a prisoner of war camp.'

Now, we collected a lot of nuns, English-speaking nuns who had been speaking, teaching in France, a lot of English people who lived in France, all trying to join us, to get out, to get back to England. And they said the Salvation Army, the YWCA [Young Women's Christian Association], and any of these people will be put in a... interned in a camp. They won't be prisoners of war like the military people will.

Description

This transcript is from a 1995 interview with Mary Coomer. (NAM. 1995-06-56)

Mary served in the Auxiliary Territorial Service from 1938 to 1945. She was one of the first to be selected to go to France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). After evacuating back to England in 1940, she served on the Home Front for the rest of the Second World War.