Defeat at Isandlwana

In January 1879, a British force commanded by Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford invaded Zululand aiming to extend British imperial influence in southern Africa.

The army was split into three columns. Chelmsford led the central column himself, crossing the Buffalo River at Rorke's Drift mission station to seek out King Cetshwayo's Zulu army.

But the British had underestimated their opponents' speed of movement and fighting ability. On 22 January 1879, 20,000 Zulu warriors launched a surprise attack against Chelmsford's camp at Isandlwana. Underprepared and dangerously strung out, the majority of the 1,700 British soldiers there were killed.

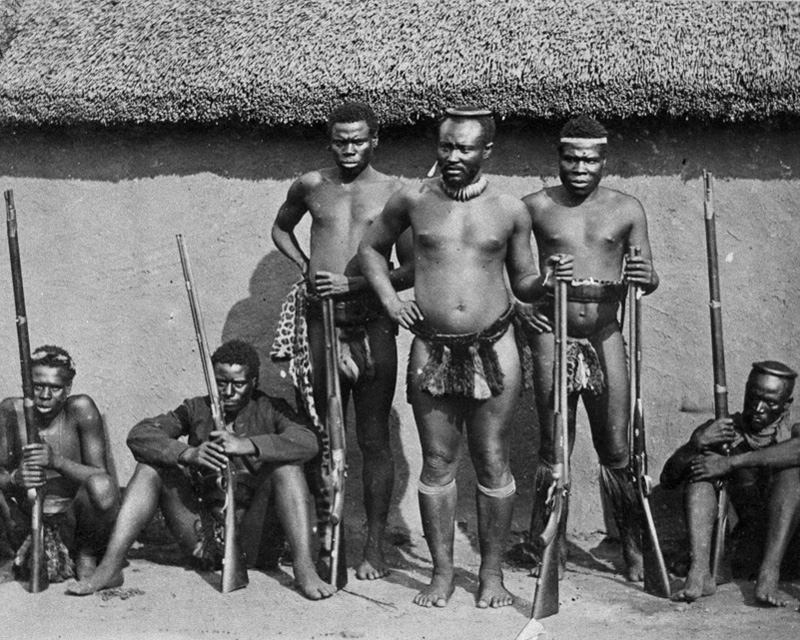

The Zulus

The Zulu army immediately pressed on to Rorke's Drift, where the British had established a depot and hospital. They were led by Dabulamanzi kaMpande (1839-86). He was King Cetshwayo's half-brother and had commanded the Undi Corps at Isandlwana.

His men were formidable warriors. They were courageous under fire, manoeuvred with great skill and were adept in hand-to-hand combat. Although they had some old-fashioned muskets and a few modern rifles, most were armed only with shields and spears.

The Zulu warriors were renowned for their use of the shorter-style assegai spear, known as the 'iklwa', which is said to be named after the sound that was heard as it was withdrawn from a victim's body. They also carried a shield made of oxhide, an 'ishilunga'.

This combination of shield and spear was deadly when used with careful co-ordination in close combat.

Fight or flight?

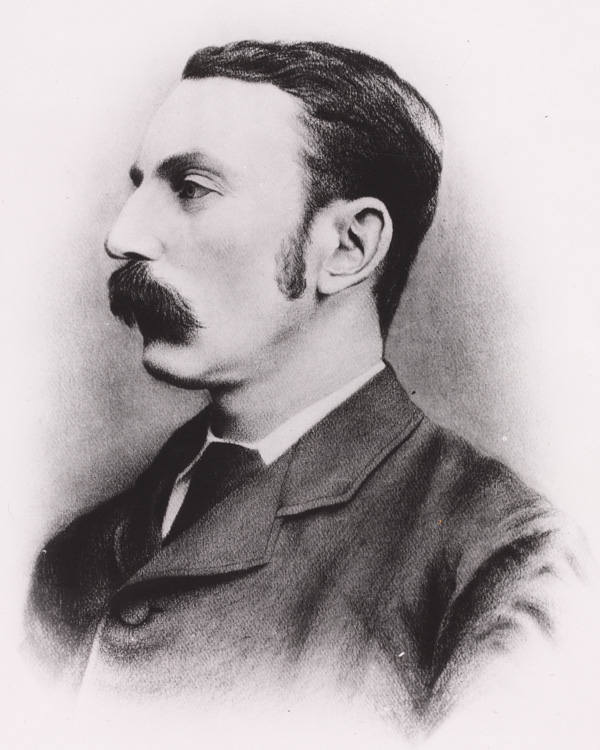

Survivors from Isandlwana soon reached Rorke’s Drift with news of the approaching Zulus. Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead met with Assistant Commissary James Dalton of the Commissariat and Transport Department to decide whether they should retreat or defend the station.

Dalton argued that their small force, travelling in open country and burdened with hospital patients, would easily be caught by the fast-moving Zulus. So it was agreed that they would stay and fight.

They set about building improvised barricades from 'mealie' (maize) bags, biscuit boxes and crates of tinned meat. The buildings were also loop-holed for defence.

The British garrison at Rorke's Drift consisted of only 150 men. They faced an army of 4,000 Zulu warriors.

The defence begins

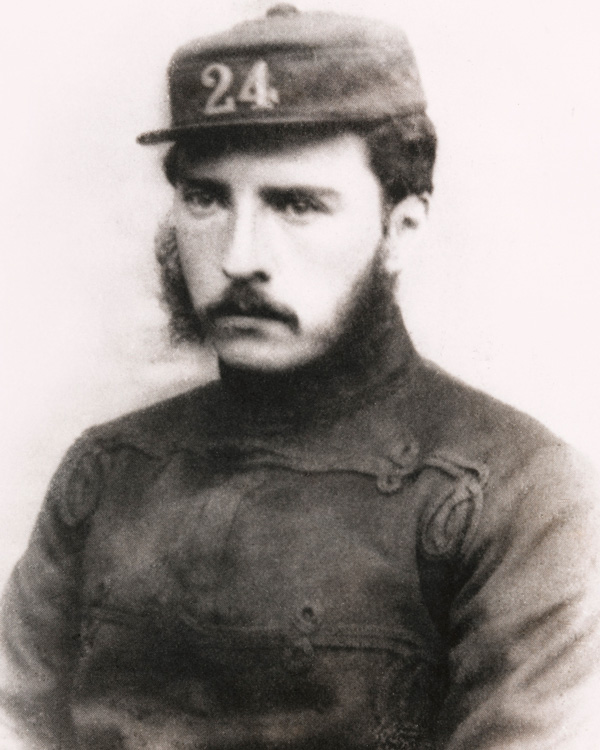

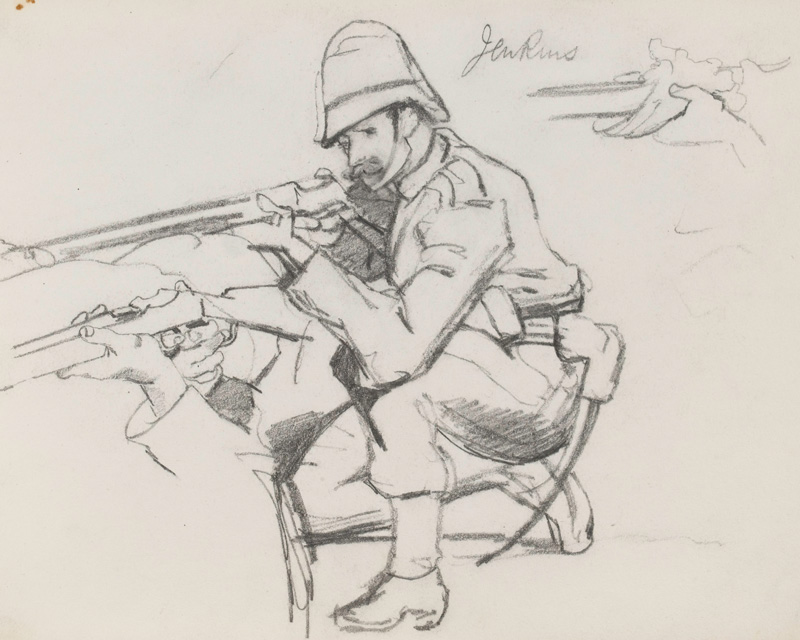

The Zulu army arrived at Rorke's Drift at 4.30pm. They spent the next 12 hours continuously storming the British defences, which were mainly held by soldiers of the 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment.

At first, they were unable to reach the men behind the barricades with their spears. Many Zulu warriors were shot down at point-blank range. And the defenders forced back any who did manage to climb over.

British soldiers who were too badly wounded to shoot, were tasked with reloading guns and distributing ammunition to those who could still fire. Many of the Zulus who had firearms lacked training and were poor shots.

As the battle raged on, the Zulus targeted the hospital. They set fire to the building, burst in and began killing the patients with their spears. But the defenders managed to push them back with bayonets.

The surviving patients were rescued after soldiers hacked holes in the walls separating the rooms, and dragged them through and into the barricaded yard.

As night fell, the British withdrew to the centre of the station, where a final defence had been hastily built. They eventually succeeded in fighting the Zulus off.

At the end of the fighting, 400 Zulus lay dead on the battlefield. Only 17 British were killed, but almost every man in the garrison had sustained some kind of wound.

Outcome

After the disaster at Isandlwana, the stand at Rorke's Drift was a welcome boost to British morale. But it had little effect on the Zulu War as a whole. The conflict continued for several months until the Zulus were finally defeated in July 1879 at the Battle of Ulundi.

King Cetshwayo was later hunted down and captured, the Zulu monarchy was suppressed and Zululand divided into autonomous areas. In 1887, it was declared a British territory, and became part of the British colony of Natal ten years later.

Corporal Christian Schiess VC

Eleven Victoria Crosses (VC) and five Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded to survivors of Rorke's Drift. One of the VCs went to Corporal Christian Schiess (1856-84). Born in Switzerland, he later settled in South Africa and joined a British colonial unit, serving throughout the Zulu War.

Schiess displayed great bravery at Rorke's Drift. He fought off the Zulus throughout the night, despite being wounded in the foot. He became the first Swiss national to be awarded a VC and the first man serving with South African forces to be decorated with the supreme British award for gallantry.

Despite his heroism, Schiess struggled to find work after the war and ended up living in poverty. In 1884, he fell ill on a sea voyage to England and died.

Legacy

The British government seized upon the successful defence of Rorke's Drift, issuing awards to the survivors in the hope of diverting public attention away from the disaster of Isandlwana.

It didn't work. Benjamin Disraeli's administration lost the 1880 election, brought down in part by the events of the Zulu War. However, it was the heroism at Rorke's Drift, rather than the defeat at Isandlwana, that passed into British folklore.

The artists Lady Elizabeth Butler and Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville both contributed to this by quickly producing highly popular paintings of the battle. Butler's 'Defence of Rorke's Drift' (1880) was shown at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1881, attracting a 'great crush' of onlookers.

Public fascination with the battle has continued through books, films and video games. It gained worldwide fame through the film 'Zulu' (1964), starring Stanley Baker, Michael Caine and Jack Hawkins. Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who would later become a politician in South Africa, played the role of his great-grandfather, King Cetshwayo.

Chard: 'The [British] Army doesn't like more than one disaster in a day.' Bromhead: 'Looks bad in the newspapers and upsets civilians at their breakfast.'Stanley Baker and Michael Caine as Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead in 'Zulu' — 1964