Early career

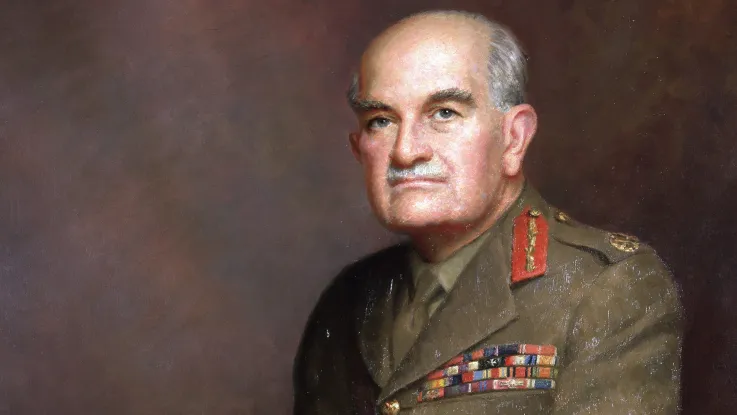

Wavell was born the son of a major-general in 1883. Graduating from Sandhurst in 1901, he joined The Black Watch and fought in the Boer War (1899-1902) and on India’s North West Frontier. He attended Staff College, spending a year in Russia as a military observer, returning in 1912 to serve as a staff officer at the War Office.

The First World War (1914-18) saw Wavell serve as a staff officer at British headquarters, before taking up a field command as a brigade major with 9th Infantry Brigade. He lost an eye in the Second Battle of Ypres (1915) and earned a Military Cross before returning to the General Staff.

There, he held several posts, including Russian liaison in the Caucasus, liaison officer with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force and Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General to the Supreme War Council at Versailles.

Inter-war

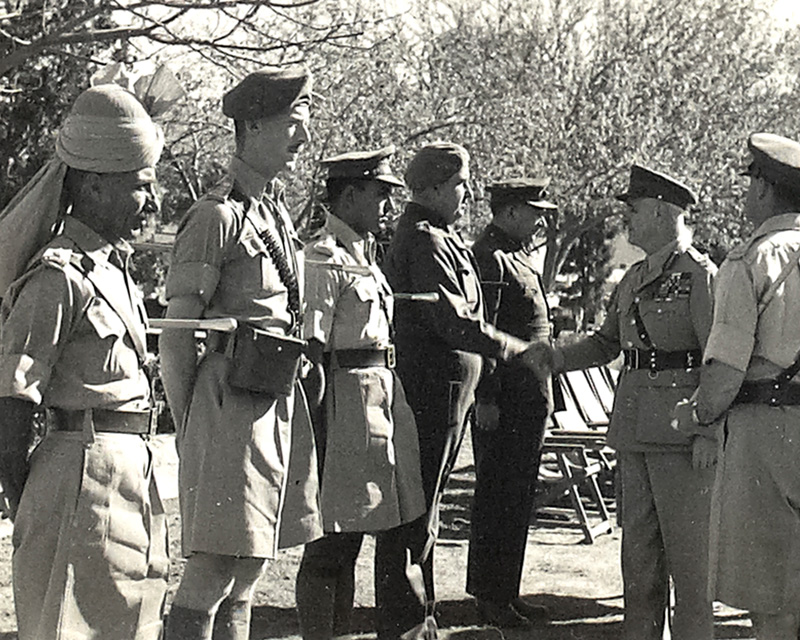

Between the wars, Wavell continued to hold important staff postings, such as Assistant Adjutant General at the War Office, and aide-de-camp to King George VI. He also commanded 6th Infantry Brigade and 2nd Division.

In 1937, he took command of British forces in Palestine and Transjordan, where there was growing political unrest. His experience in the Middle East saw him appointed head of Middle East Command in 1939.

Second World War

In February 1940, Wavell also assumed responsibility for East Africa, Greece and the Balkans. His title changed to Commander-in-Chief Middle East.

Italy entered the war in June 1940, greatly outnumbering British forces in North and East Africa. Wavell withdrew his men into Egypt, luring the Italians into over-extending before counter-attacking them first in Libya in 1940, and then in Eritrea and Ethiopia in 1941.

By February 1941, Wavell had overrun the Italian Tenth Army, capturing 130,000 prisoners, and driving nearly all Axis forces from North Africa.

He had proved himself a fine strategist with foresight, appreciation of enemy weaknesses and an understanding that logistics were key to success in the desert.

‘Wavell’s star rose high at an early stage of the war. Its glow was the more brilliant because of the darkness of the sky. His victories in North Africa and East Africa in the winter of 1940-41 were Britain’s first striking successes after the catastrophic run of defeats in the West. They came as a great tonic – not only to the British but even more to others who had been shocked and alarmed by the apparently irresistible advance of the Nazi and Fascist dictators.'Captain Basil Liddell Hart — 1950

Greece

However, in April 1941, the Axis launched a Balkans offensive that threatened Greece. Wavell was ordered to halt his advance in North Africa to free men for service in Greece and Crete. He was opposed to this decision, as he believed victory was close at hand. But ultimately he obeyed his orders.

As a result, his weakened Western Desert Force was unable to hold back Rommel’s Afrika Korps, who were reinforcing the Italians. In Greece, the men he had reluctantly sent were soon forced to evacuate, abandoning all their heavy equipment and artillery.

Tobruk

Wavell again withdrew to Egypt, leaving Tobruk besieged for 240 days. In June 1941, he was forced to detach more troops to take Syria and Lebanon from the Vichy French. This operation eventually succeeded, but further weakened his North Africa force.

He was given the opportunity to relieve Tobruk, but Rommell’s brilliant defensive tactics saw the operation end in failure. Prime Minister Winston Churchill replaced Wavell with General Sir Claude Auchinleck, who nevertheless praised his predecessor for his work.

Rommel also rated Wavell as a general. He kept a copy of the latter’s book 'Generals and Generalship' (1941) with him during the desert war.

Far East

Wavell next became Commander-in-Chief in India. Following the Japanese declaration of war in December 1941, he was made Commander-in-Chief of American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (Abdacom), responsible for the defence of India, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (now Malaysia), the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and the Philippines.

Again finding himself vastly outnumbered and under-resourced, he was unable to prevent Malaya and Singapore falling into Japanese hands in 1942.

Burma

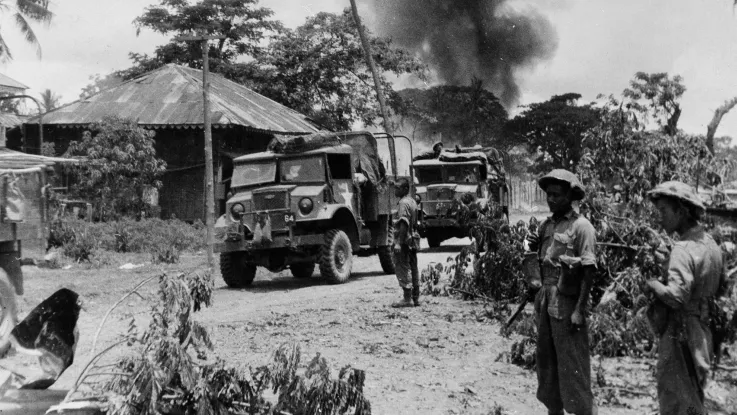

Following the dissolution of Abdacom, Wavell returned to the role of Commander-in-Chief in India. His most urgent task was the defence of Burma, where the British position quickly deteriorated.

As the Japanese pushed northwards, the surviving Allied troops carried out a fighting retreat to India across 1,000 miles (1,600km) of difficult terrain. One of Wavell’s most important acts at this time was bringing General William Slim from the Middle East to assist with the retreat.

In order to wrest the initiative from the Japanese, Wavell ordered the Eastern Army in India to attack the Arakan in September 1942. But after initial success, the Japanese counter-attacked. By March 1943, the British position was untenable and the force was withdrawn.

Wavell also sanctioned the Chindits. Their attacks behind the lines in Burma raised morale and demonstrated that British soldiers could live and fight in the jungle.

‘Knowing him, and something of his deeds, it was impossible not to believe in greatness. In that square figure was housed a spirit of grandeur, and with his massive heroism went gentleness and modesty, even humility. He had no need to proclaim his virtue, for history would be his spokesman.’Writer and war veteran Eric Linklater — 1950

India

In September 1943, Wavell - now a field marshal - was appointed Governor General and Viceroy in India, effectively ending his military command duties.

In this role, he tried to alleviate the Bengal famine of 1943 by ordering the Army to distribute relief supplies. He also helped control the communal tension and civic strife that later exploded during the Partition of India.

Although he was against the idea of Partition, believing it would lead to bloodshed, Wavell helped lay the foundations for Sir Cyril Radcliffe’s Border Commission.

However, in the lead-up to independence, he struggled to deal with the rival Indian political factions. He eventually lost the faith of Prime Minister Clement Atlee, who replaced him with Admiral Louis Mountbatten in 1947.

On his return to England, he was created Earl Wavell. He died just three years later in 1950.