Early career

The son of a wealth whisky distiller, Haig (1861-1928) was born in Edinburgh into a large family of ancient Scottish lineage.

He joined the British Army in 1884 where he excelled at polo, saw active service in Sudan and South Africa and became a recognised authority on cavalry warfare.

Haig's assiduity, aptitude for staff work and social connections enabled him to rise swiftly though the ranks and to secure the prestigious command of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France in December 1915.

He took command of the BEF at a time when it was locked in entrenched stalemate with the Germans along the Western Front.

Offensives

Under his direction the British Army launched a series of mighty offensive against the German lines, the most famous of which were the battles of the Somme (1916) and Passchendaele (1917). These offensives resulted in huge casualties but failed to break the deadlock or to win significant territory.

Attrition

Haig has since been accused of being an out dated cavalryman wedded to a belief in the possibility of breakthrough, failing to appreciate the realties of the new attritional warfare where success was measured not in territory captured but by a favourable casualty ratio.

Haig has also been accused of stubbornness – certainly at Passchendaele he continued the offensive long after it was clear to many that men were dying for relatively little strategic gain.

‘A second-rate Commander in unparalleled and unforeseen circumstances… He was not endowed with any elements of imagination and vision… And he certainly had none of that personal magnetism which has enabled great leaders of men to inspire multitudes with courage, faith and a spirit of sacrifice… He was incapable of planning vast campaigns on the scale demanded on so immense a battlefield’.Wartime Prime Minister David Lloyd George on Haig — 1935

Tough lessons

Yet in both battles Haig and his subordinates learnt a tough lesson in how to fight a large-scale war. A more professional and effective army emerged from them. The tactics developed in these grim struggles, including the use of tanks and creeping barrages, laid the foundations of the Allies’ successful attacks in 1918. Likewise, the battles of Arras and Cambrai saw the adoption of new methods such as sound ranging and flash spotting to pin-point enemy guns, infantry-tank co-ordination and close air support.

In Haig’s defence some historians now tend to blame the horrific casualties more on the nature of trench warfare and the British Army’s inherent shortcomings rather than the mistakes of individual commanders. Haig has also been commended for his commitment to the war winning strategy of defeating the Germans on the Western Front.

All Arms

To this end, he oversaw the greatest expansion of the British Army in its history and worked tirelessly to ensure that it evolved into a mighty and sophisticated instrument of war.

By the summer of 1918 the British Army was in the vanguard of the Allied counter offensive that broke the Germans. Under Haig’s command it perfected the ‘All Arms’ strategy that combined tanks, artillery, infantry, cavalry and air power.

Duty

Haig’s character remains a mystery. He has been depicted as a callous and incompetent man who obstinately persisted with costly and futile offensives driven by a boundless yet ill-founded optimism. In contrast, he has been commended for his determination and devotion to duty; a man who stoically bore a burden of responsibility that would have broken lesser men.

His involvement in the founding of the Royal British Legion exhibited his deep concern for the suffering of ex-servicemen.

Backs to the wall

While he lacked the charisma of a Napoleon or a Patton, Haig was certainly capable of stirring words, as with his famous ‘Backs to the Wall’ order of April 1918 when the German Spring Offensive looked like succeeding. Nicknamed ‘the Chief’ by his troops he had their respect if not their love.

Diplomat

Haig was also flexible enough to work with difficult allies. He had to be a diplomat when dealing with the French, who for the first three years of the war were the senior partner in the entente. He also had to work with the Americans, Belgians and Portuguese.

'If there are some who would question Haig’s right to rank with Wellington in British military annals, there are none who will deny that his character and conduct as a soldier will long serve as an example to all'.Winston Churchill on Haig — 1938

Reputation

When Haig died in 1928 vast numbers attended his funeral, testament to the high regard in which he was held by his contemporaries. Yet today he is widely perceived as the archetypal bungling First World War general.

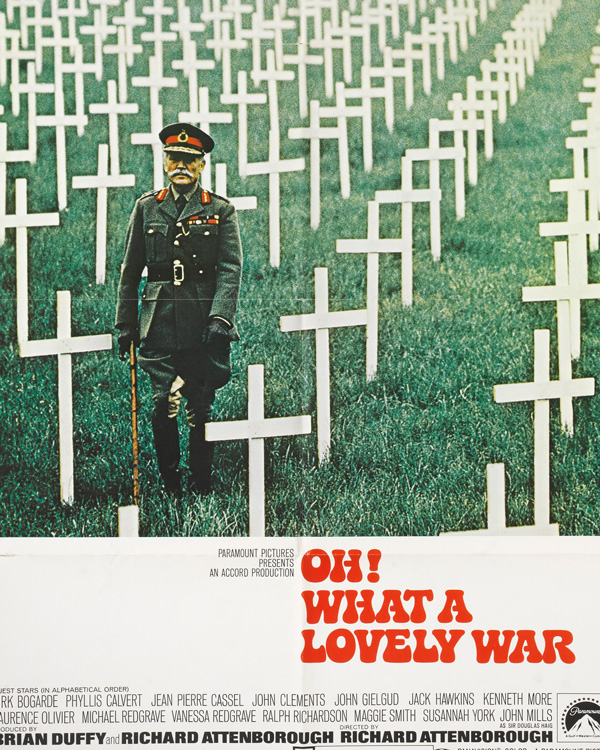

His reputation was attacked in the 1930s by historian Basil Liddell Hart and wartime prime minister David Lloyd George. In the 1960s he was criticised by Alan Clark in his book ‘The Donkeys’ (1961). Joan Littlewood’s musical ‘Oh! What a Lovely War’ (1963) and later the BBC comedy ‘Blackadder Goes Forth’ (1989) added to the negative perception.

More recently, writers like John Terraine, Gary Sheffield and William Philpott have re-assessed Haig's contribution to winning the war. But despite their best endeavours, the popular view is still one of an incompetent commander.