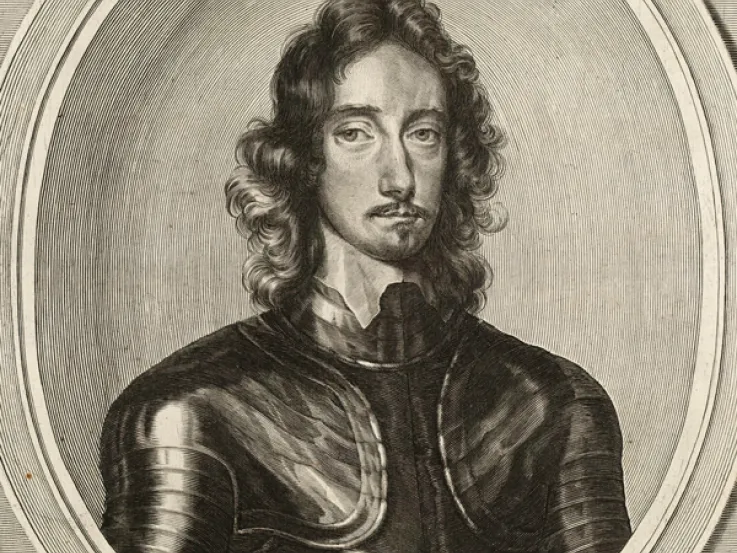

General Oliver Cromwell at Marston Moor, 1644

MP and soldier

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) came from an impoverished East Anglian gentry family. He was a small landowner and Member of Parliament (1628-29 and 1640-42).

Remarkably, he was over 40 years old when he began his military career. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642, he served as captain of a troop of horse which he raised for Parliament. Within a year, he had risen to the rank of colonel, with command of a regiment.

Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, c1653

Commander

Cromwell realised instinctively that good quality, disciplined troops, motivated by religious zeal, were the key to victory. He recruited his men accordingly. He would later help establish the New Model Army, a force of men chosen for their prowess and dedication rather than by name or wealth.

In 1643, by his own energy and decisive action, he largely eliminated Royalist resistance in East Anglia and secured it for Parliament, gradually expanding his base by successful forays into Lincolnshire.

‘I had rather have a plain, russet-coated Captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a Gentleman and is nothing else.’

Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell - 1643

Eastern Association

In February 1644, Cromwell was appointed cavalry commander of the Army of the Eastern Association, a Parliamentarian force recruited mostly in East Anglia.

In July that year, this army formed part of the Parliamentarian forces at the Battle of Marston Moor, in which Cromwell commanded the cavalry of the left wing. The discipline of his troopers enabled them to deliver a decisive charge at the end of the battle.

The following year, Cromwell played a similar role at the Battle of Naseby. His men were able to drive off the opposing cavalry and then turn upon the flank of the Royalist infantry, ensuring a Parliamentarian victory.

The Battle of Naseby, 1645

Second Civil War

It was not until the Second Civil War (1648-49) that Cromwell fought his first major battle in full command. At Preston, in August 1648, he inflicted a crushing defeat on the Scots, despite facing greatly superior numbers. This victory destroyed Royalist hopes and effectively ended the war.

Cromwell was one of the signatories of King Charles I’s death warrant in 1649. He dominated the subsequent Commonwealth period as a leading member of the Rump Parliament (1648-53).

King Charles I, c1649

Cavalry of the New Model Army, c1645

Ireland

Cromwell is perhaps best remembered for his campaign in Ireland (1649-50), undertaken by Parliament to eliminate support for the exiled King Charles II. The campaign opened with massacres at Drogheda and Wexford, where there was widespread slaughter of Catholic soldiers and civilians alike.

Cromwell justified this on the grounds that it was consistent with the laws of war and that it would encourage more rapid surrenders elsewhere, thus saving lives. Many other Royalist garrisons did indeed surrender when Cromwell offered them generous terms, but Ireland remains a blot on his reputation.

He also continued the practice, set in motion the previous century, of settling Protestants on confiscated Irish land. As a result, he came to symbolise this hated policy which gave England political dominance in Ireland.

General Oliver Cromwell taking Drogheda, 1649

General Oliver Cromwell, c1645

‘This is a righteous judgement of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are satisfactory grounds for such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret.’

Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell after the Siege of Drogheda - 1649

Scotland

In 1650, Cromwell led a pre-emptive invasion of Scotland to strike at Scottish support for King Charles II. At first out-manoeuvred by the Scots, he achieved a brilliant victory at the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650, despite being outnumbered almost two-to-one.

A year later, he won a crushing victory over the Scots at the Battle of Worcester. This was to be his last major field action.

The Battle of Worcester, 1651

Medal commemorating Cromwell's victory at Dunbar in 1650

Lord Protector

From September 1651, Cromwell was primarily a statesman rather than a soldier. He used the Army to disband the Rump Parliament in 1653, irritated by its self-serving interests and slowness in developing solutions for the Commonwealth. In the process, he became Lord Protector.

But Cromwell could not agree with his Protectorate Parliaments either. He dismissed them and, instead, ruled the country through his major-generals. England was now virtually a military dictatorship.

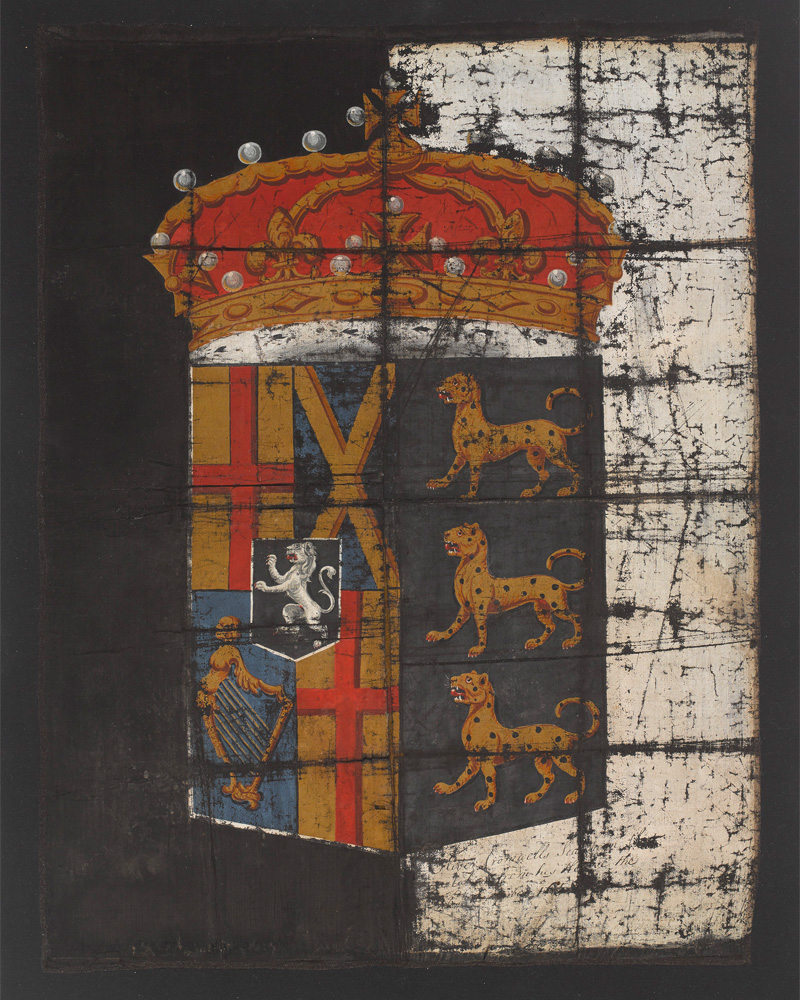

Oliver Cromwell's funeral banner, c1658

Death and legacy

Cromwell retained the position of Lord Protector until his death in 1658. He was given a state funeral, as elaborate as those of the kings who came before him, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

In 1661, following the Restoration of the monarchy, his body was dug up. His corpse was subjected to a posthumous execution and his severed head was placed upon a pole outside Westminster Hall - a potent public act that recast him as a traitor.

Throughout his turbulent career, Cromwell attributed his success to Divine Providence. But his energy, personal example and ruthlessness are all the qualities of a great battlefield commander.