The Battle of Blenheim

13 August 1704

Fought during the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-13), Blenheim saw the Duke of Marlborough lead an Allied force against the French. Although outnumbered, he realised that his enemies' position did not allow them to move easily around the battlefield.

He pinned down the French flanks and then delivered a crushing blow with his 80 cavalry squadrons against the enemy’s weakly defended centre. His horsemen stormed across the Nebel stream and attacked the disorganised French cavalry, who were routed.

Marlborough’s cavalry then wheeled left and joined the infantry in forcing the French into the River Danube, where many drowned. France suffered its first major defeat for 40 years, losing over 30,000 casualties and having its commander-in-chief captured.

‘In the finest array, the allied cavalry, mustering 8,000 sabres, moved up in two lines – at first slowly, but gradually more quickly as they drew near, and the fire of the artillery became more violent… With irresistible vehemence the line dashed forward at full speed, and soon the crest of the ridge was passed. The French horsemen discharged their carbines with little effect, and immediately wheeled about and fled… The allied horse rapidly inundated the open space... The six battalions in the middle were surrounded, cut to pieces, or taken.’Sir Archibald Alison, ‘Life of Marlborough’ — 1848

The Battle of Emsdorf

14 July 1760

At the Battle of Emsdorf, during the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), the British and Hanoverian troops surprised their French enemies before they could form up properly. Colonel George Eliott's 15th Light Dragoons then repeatedly charged the French as they tried to retreat.

They broke five battalions of enemy infantry in rapid succession before capturing five guns and a howitzer. They also took 1,650 prisoners, including the French commander Marshal Glaubitz and the Prince of Anhalt.

‘His Serene Highness, therefore, gives his best thanks to these brave troops, and particularly to Eliott's regiment. His Serene Highness the Prince could not enough commend... the bravery, good conduct, and good countenance, with which this regiment fought.’Prince of Brunswick’s General Order — 20 July 1760

The 15th Dragoons later presented King George III with nine colours that they had captured at the battle. In return, he ordered them to wear the title ‘Emsdorf’ on their light dragoon helmets. This was the first ever battle honour awarded.

The Battle of Waterloo

18 June 1815

At Waterloo, the famous battle between the Duke of Wellington and the French Emperor Napoleon, four huge columns of French infantry marched on the outnumbered Anglo-Allied forces.

Wellington’s infantry could not hold off Napoleon’s forces for long. But two British cavalry brigades were hidden behind a ridge. When the order came, they surged over the ridge straight towards the enemy.

‘Nothing could stop the men; they went on, took a great many of the enemy’s guns, and then, instead of halting, charged the lancers and cuirassiers. At this moment, I lost sight of the General, who was killed, and cut my way to the rear, we being completely overpowered.’Lieutenant Archibald Hamilton, 2nd (Royal North British) Regiment of Dragoons describing the charge — 1815

The force of the British charge smashed through the French infantry. But the lack of control meant the British heavy cavalry rode too far and were eventually destroyed when French cavalry counter-attacked.

Losses were high on both sides, but the Royal Scots Greys and the 1st Royal Regiment of Dragoons won a symbolic victory by capturing two of Napoleon’s French eagle standards.

The Peterloo Massacre

16 August 1819

On 16 August 1819, a meeting was held at St Peter’s Field in Manchester. It had been organised by the Manchester Patriotic Union Society, a political group calling for parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws. At least 60,000 people attended.

Local magistrates were concerned that the meeting would cause a riot and they arranged for 600 troops to be present. All was peaceful until the magistrates attempted to end the meeting. After the Riot Act was read, the cavalry tried to arrest the speakers by cutting their way through the crowd with sabres.

Eleven were killed and over 400 people, including women and children, were trampled by cavalry horses. The events were reported in the ‘Manchester Observer’, which coined the phrase ‘Peterloo Massacre’ to describe the event in ironic reference to the recent Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

‘The Yeomanry Cavalry made their charge with a most infuriate frenzy; they cut down men, women and children, indiscriminately, and appeared to have commenced a pre-meditated attack with the most insatiable thirst for blood and destruction.’Richard Carlile in ‘Sherwin’s Weekly Political Register’ — August 1819

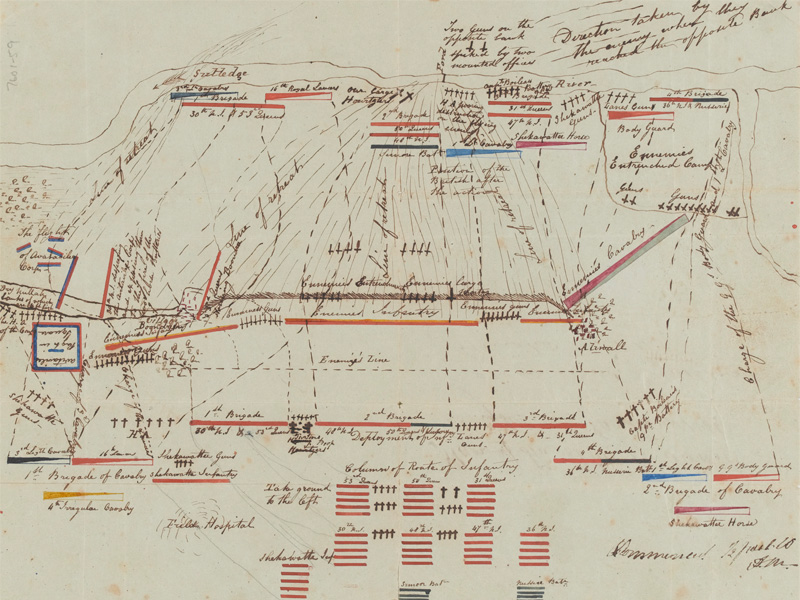

The Battle of Aliwal

28 January 1846

In 1845-46, the British fought a war against the powerful Sikh state of the Punjab. The Sikh cavalry was highly skilled and very effective against the British Army when it was spread out on the march. They had successfully captured most of the British baggage animals before the battle at Aliwal.

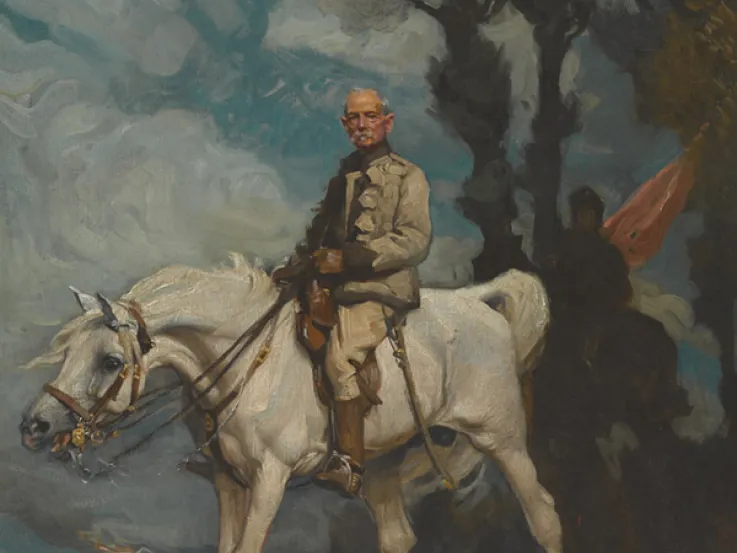

Sir Harry Smith led the British. He was an experienced soldier who had fought in the Napoleonic Wars. He stayed calm until his army was ready to attack.

‘I directed a squadron of the 16th Lancers… to charge a body to the right of a village, which they did in the most gallant and determined style, bearing everything before them… going right through a square in the most intrepid manner with the deadly lance.’General Sir Harry Smith — 1846

During the battle, the 16th (The Queen’s) Lancers charged into the Sikh infantry. Major John Smyth led the attack with a cry of ‘Boys, three cheers for the Queen… Lancers Charge’.

Smyth was among the many lancers wounded, but several Sikh guns were captured or put out of action. The infantry and horse artillery then drove the Sikhs from the battlefield.

Battle of Balaklava

25 October 1854

The Battle of Balaklava, during the Crimean War (1854-56), witnessed two of the most famous cavalry charges in British Army history.

The first major charge of the battle was by the Heavy Brigade. A large Russian cavalry force had been repelled by the ‘Thin Red Line’ of British infantry, but stopped as it came towards the British camp. This mistake laid it open to attack, and the British heavy cavalry charged.

With luck and skill, the outnumbered British drove the Russian horsemen from the field. This action, said to have been over in eight minutes, showed how strong cavalry could be, even against superior numbers.

‘It was truly magnificent; and to me who could see the enormous numbers opposed to you, the whole valley being filled with Russian cavalry, the victory of the Heavy Brigade was the most glorious thing I ever saw.’A French general addressing Colonel Beatson — 25 October 1854

The other major charge at Balaklava was the Charge of the Light Brigade - one of the Army's best-known blunders. It came about because of poor communication and the inexperience of the officers involved.

The British commander, Lord Raglan, was keen to follow up the Heavy Brigade’s success. Overlooking the battle from high up on a hill, he gave the order for the cavalry to stop the Russians carrying off some British artillery they had captured earlier on.

But Lord Lucan, in charge of the cavalry, was positioned down in a valley. The only artillery he could see was a battery of Russian guns. Despite his confusion at Raglan's order, he sent Lord Cardigan to attack them with the Light Brigade.

The men and horses bravely charged through heavy fire at the Russian guns. Within 20 minutes, more than 260 men had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, and 475 horses were lost.

The Battle of Killa Kazi

11 December 1879

Following the deaths of the British resident and his guard at Kabul in September 1879, the 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers joined Major-General Sir Frederick Roberts on the march to the Afghan capital. On 11 December, a squadron of the regiment encountered a huge Afghan force near Killa Kazi.

Roberts wanted to delay the enemy’s advance on Kabul, so gave the order for 170 men to charge around 10,000 Afghans. Losses were heavy. The 9th Lancers suffered 18 officers and men killed, and 10 more wounded. 46 horses died.

Despite their severe mauling, the 9th Lancers remained in Kabul until August 1880, when it joined Roberts's epic 300-mile (480km) relief march to Kandahar.

‘The ground, terraced for irrigation purposes and intersected by nullahs, so impeded our cavalry that the charge, heroic as it was, made little or no impression upon the overwhelming numbers of the enemy. The effort, however, was worthy and that it failed in its object was no fault of our gallant soldiers.’Major-General Sir Frederick Roberts describing the action at Killa Kazi — 1879

The Battle of Kassassin

28 August 1882

In August 1882, an Egyptian army led by Ahmed Urabi attacked the British troops at Kassassin in order to recapture the Suez Canal. The outcome of the battle was in the balance until the arrival of British reinforcements who finally broke the Egyptians.

Legend has it that the Household Cavalry regiment arrived as it was getting dark, and immediately went into action. By moonlight, they cut their way through the Egyptian infantry to reach a battery of guns behind them.

Queen Victoria herself had specially requested the inclusion of the Household Cavalry in General Sir Garnet Wolseley’s expeditionary force. Their ‘midnight’ or ‘moonlight’ charge became one of the most famous incidents of the Egyptian War (1882).

‘By this time the moon had risen. Squadrons showed up black, and flash answered flash as the opposing guns opened one on the other. The order now came to charge, and away went the Household Squadrons led by the gallant Ewart. Into the Egyptian infantry and up to the guns they went.’Description of the charge at Kassassin, 'The London Gazette' — 1882

Battle of Omdurman

28 September 1898

The British were hugely outnumbered by the Sudanese Dervish tribesmen at Omdurman. But they had superior firepower and had mown down their enemy in the first phase of the battle.

General Herbert Kitchener, who was commanding the British-Egyptian army, was anxious to capture Khartoum before the remaining Dervish force could retreat there. He ordered the 21st Lancers to clear the route ahead. The lancers were so eager to attack that the trumpeter barely had time to sound the ‘trot’ before they charged.

‘They were as thick as bees and hundreds must have been knocked over by our horses. My charger – a polo pony – behaved magnificently, literally trampling straight through them.’Lieutenant René de Montmorency, 21st Lancers — 1898

The lancers could only see a small part of the enemy force and could not stop before rushing into a gully full of 2,500 hidden tribesmen. The Dervishes stood their ground, killing 21 lancers and wounding many more.

Half the 447 horses on the charge were also killed or hurt. But the lancers regrouped and proceeded on foot, using their carbines to drive off the enemy.

Some officers thought the infamous action of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman was reckless. Others saw it as proof that cavalry were still more than just mounted infantry.

Lance pennant carried at Omdurman, 1879

Battle of Elandslaagte

21 October 1899

During their invasion of Natal, the Boers captured the railway station at Elandslaagte, cutting communications with Ladysmith and Dundee. The British responded by driving them out of this position with the skilful deployment of dismounted cavalry units and infantry.

As the Boers mounted their horses and started to retreat, two British cavalry squadrons charged them three times as darkness was setting in. Many Boers were cut down and two field guns were captured. The attack was one of the few successful cavalry charges of the Boer War (1899-1902).

‘With levelled lances and bared sabres the two squadrons dashed forward and rode over and through the panic-stricken burghers. As soon as the latter heard the thud of the galloping horses and the cries of the troopers, they opened out and tried to save themselves by flight... For a mile and a half the Dragoons and Lancers over-rode the flying enemy. Then they rallied and galloped back to complete the havoc and to meet such of the fugitives as had escaped the initial burst.’Official report of the action at Elandslaagte — 1899

Bit from the Boer Commandant Johannes De Hock's horse, taken after Elandslaagte, 1899

Queen's South Africa Medal belonging to Trooper John Pike of the 1st Imperial Light Horse, 1899

The Battle of Mons

24 August 1914

Captain Francis Grenfell led a charge of the 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers at Audregnies in Belgium during the First World War (1914-18). Grenfell was an accomplished horseman and a fine polo player, but the charge he led was a disaster.

The lancers faced an unbroken German line of rifle, machine-gun and artillery fire before being halted by barbed wire. Casualties were high and Grenfell himself was severely wounded. But as the commander, he remained a rallying point for his troops in spite of his injuries. Later, Grenfell and his men also helped save British guns from capture.

‘That charge was as futile and as gallant as any other like attempt in history on unbroken infantry and guns in position. But it proved to the world that the spirit which inspired the Light Brigade at Balaclava… was still alive in the cavalry of to-day.’John Buchan, ‘Francis and Riversdale Grenfell: A Memoir’ — 1920

Grenfell was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) for this action. His citation was the first officially listed in ‘The London Gazette’. Because of this, some recognise his VC as the first of the war, even though it was not the first to be awarded. Grenfell was killed in action a year later on 24 May 1915 after being wounded twice at Hooge.

An end to the charge

Even in the 17th and 18th centuries, the success of fighting on horseback was limited by weapons like stakes, pikes and cannon, and tactics like forming infantry into squares or volley fire. But it was the awful casualties caused by modern artillery, rifles and machine-guns that ultimately rendered cavalry charges ineffective.

Nevertheless, the King's Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, still practises charging as part of their annual training sessions on the beaches of Cornwall. The exercise is distinctly different from a battle charge, but it helps to build trust and confidence between horse and rider, and prepares the animals for unpredictable events that may occur while on ceremonial duties in London.